The Jericho Skull: Just as they were about to leave the site, someone spotted a skull jutting out at an angle

The 9,500 year old Jericho skull at the British Museum has been given a new facial reconstruction, muscle by muscle, to reveal a three-dimensional portrait of a middle-aged man with the help of CT scans

Old Jericho (or Tell es-Sultan), as the local signposts will tell you, is the oldest city in continuous habitation in the world. Humans have occupied the site for 12,000 years. In 1953 a group of archaeologists led by Kathleen Kenyon happened upon an extraordinary discovery. They had been digging at a mound, and just as they were about to leave the site, someone spotted a skull, jutting out at an angle, partially exposed. It wouldn’t survive unless someone did a bit of careful work to remove it... Easier said than done.

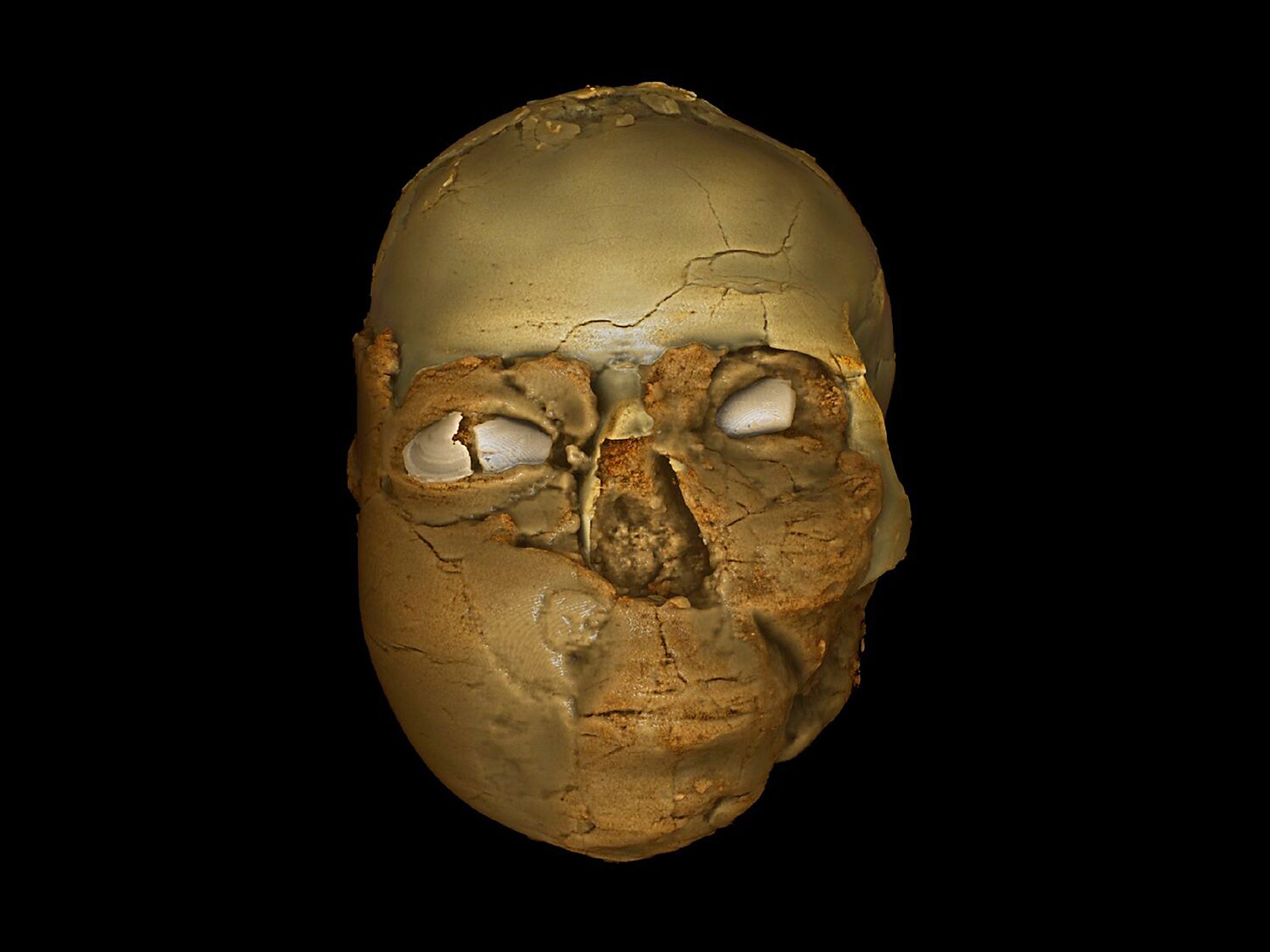

This proved to be one of a cache of several. One of them came to the British Museum. When pieced together from fragments, it proved to be a curiously fascinating object, a human skull wrapped in plaster. Its eyes were made from the kind of clam shell you would find in a good spaghetti vongole. You can see bare bone above the crude plaster edges. The bone is splintered at the top. It looks like a stitched seam. This splintering would have been caused by the weight of soil bearing down upon it over hundreds of years. Look at it from the side, and you can see finger prints of the person who would have pressed the soil into the skull.

This doll-like object – its cheeks are bulbous, and they have the smoothness of porcelain – seemed to be asking questions that technology was incapable of answering. Until now. Only X-rays were available then. Now we have CT scanning, which enables us to see behind and inside the skull without violating it physically. Who was the human being behind the ritualistic object then?

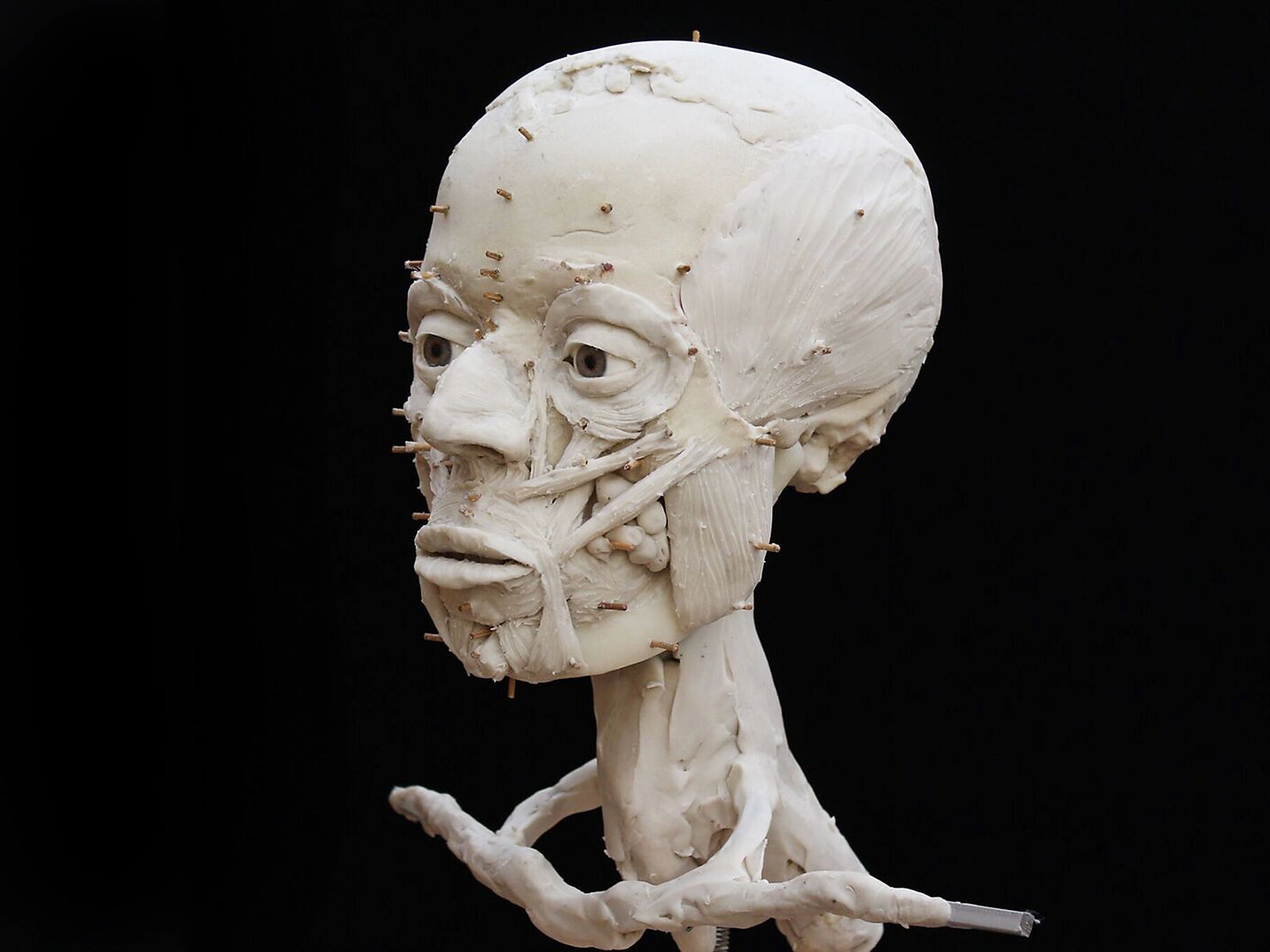

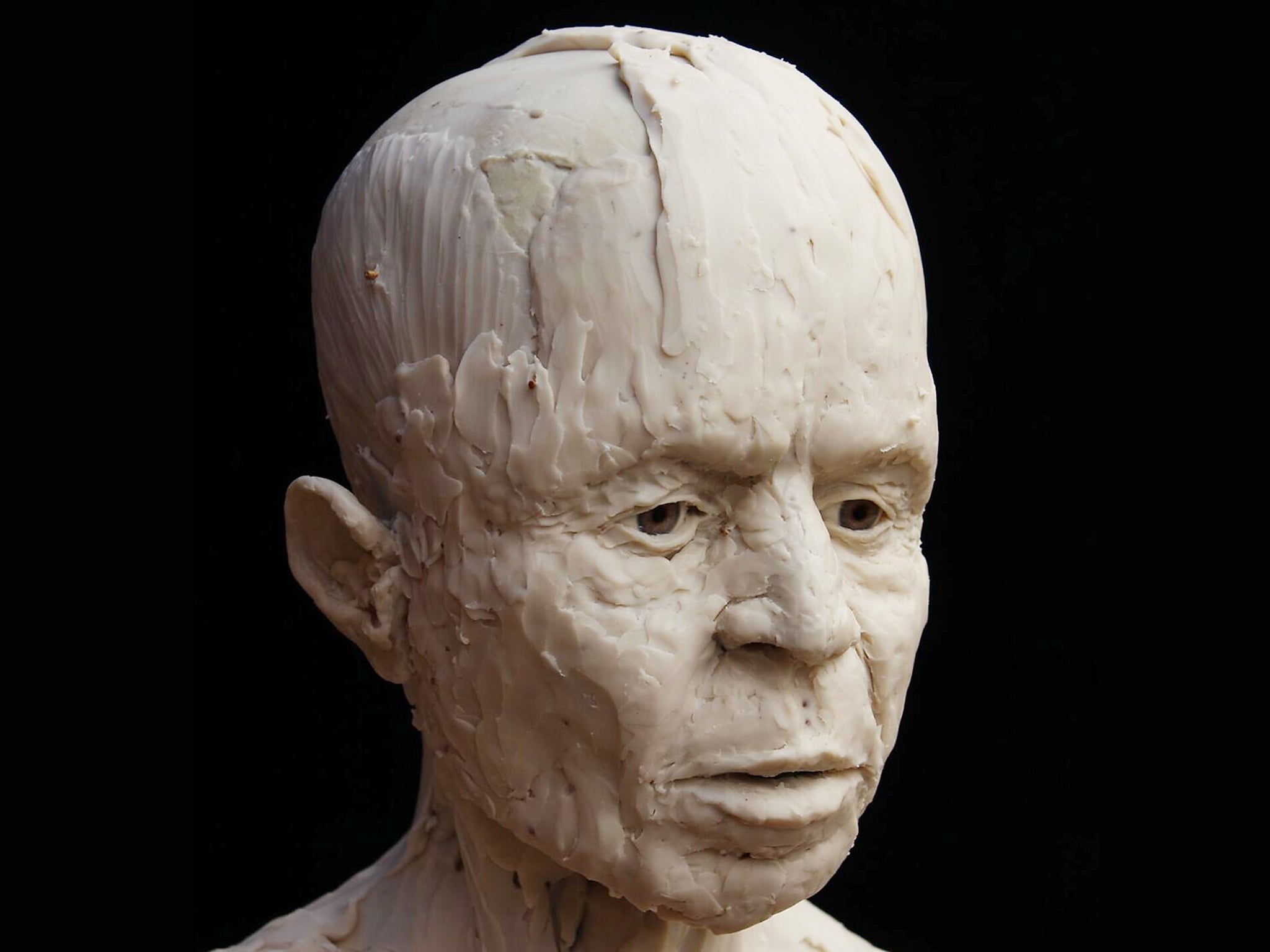

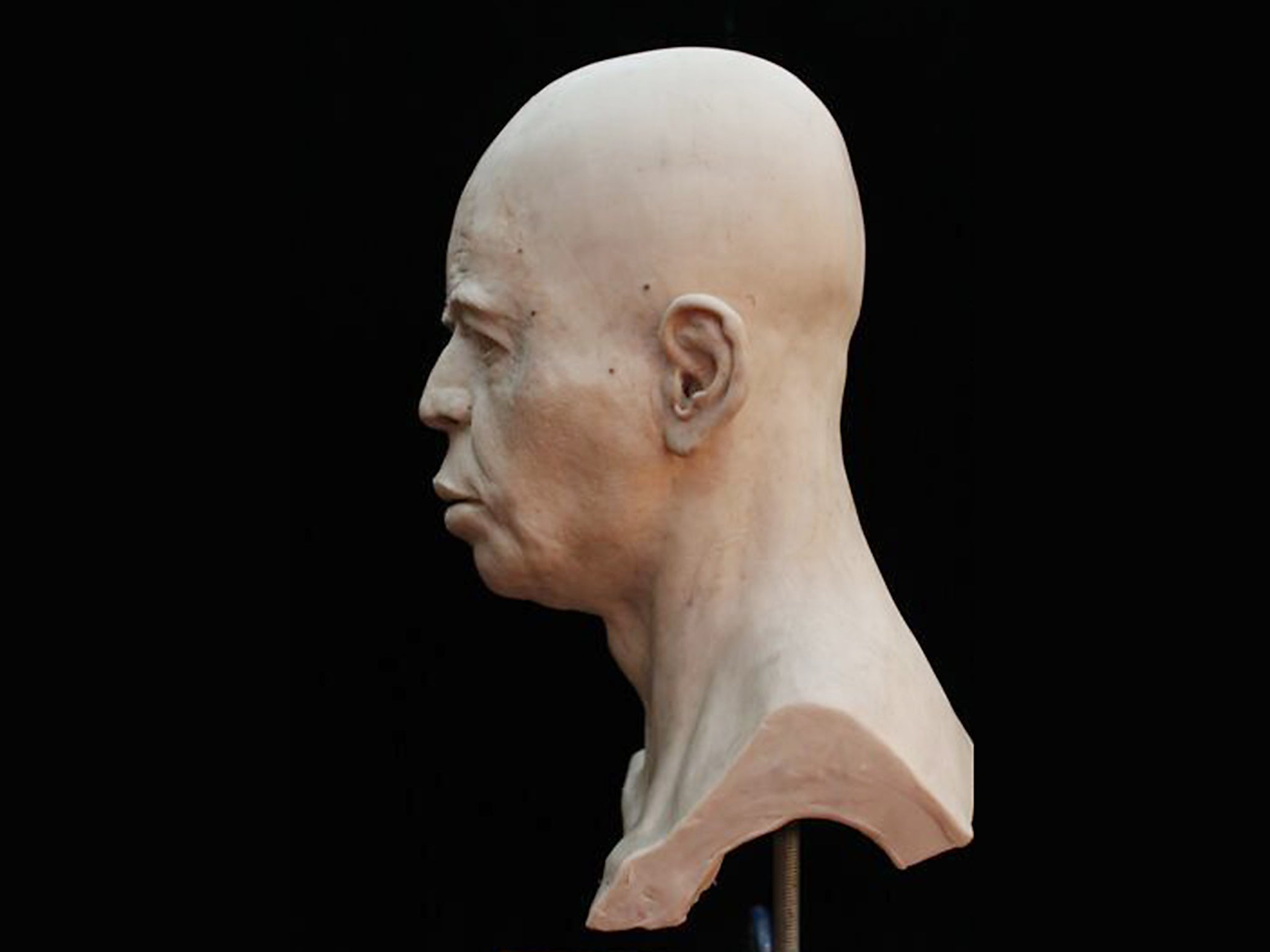

This new display at the British Museum is the outcome of a collaboration with the Imaging and Analysis Centre of the Natural History Museum. The Centre did a non-invasive micro CT scan of the skull, examining it layer by fine layer. That scan showed the varying thicknesses of the skull – solid proof that it had been bound. A 3D image was then printed out. After that, the human face behind the mask was modelled in jesmonite – the face was re-built, muscle by muscle – and what emerges is a three-dimensional portrait of a middle-aged man somewhat like you or me. The eyes are small, the lips full and fleshy, the brow furrowed. Not quite like you or me though. The skull is stretched tall, exaggeratedly so – rather like an egg.

Other facts emerged. The teeth were badly decayed – this was a man who would have suffered from howling toothache. The nose had been broken during his lifetime – you can see that by peering up into the nasal cavity of the 3D model. The skewed septum is clearly visible. The lower jaw was missing – a new one had to be created. A blow to the back of the skull suggests that he may even have been murdered. Soil was poured into a hole at the back of the cranium so that the skull would not collapse in on itself over time.

“The head of the man was bound from a very early age,” Alexandra Fletcher, curator of the show, explains. “We don’t know exactly why.

“After death, the skull was treated in this way, first removed and then decorated. When it was done, there would have been those who still knew this man. As time went on, memories of that particular individual would have faded. He would have become a more generalised image of an ancestor. This kind of exercise helps to connect us with the past; it closes the gap between ourselves and deep pre-history. It also reminds us that perhaps head-binding is not so odd after all. This man was no freak.”

But why transform a human being into a strange object of ritual anyway? What exactly was the purpose? Perhaps it is something to do with social cohesion. These skulls were objects of use – they were handled time and time again. But once they had lost their use, once they had become exhausted by over-use, they were deposited in the ground with great care. They had been precious things. Perhaps they still possessed dangerous powers. They may even have been regarded as ancestral presences, watchful over-seers or judges, who linked the past with the day-to-day. They gave everyone a sense of belonging, collectively, to a particular place. Elevation from the ordinary transformed them into objects of awe and wonder. They helped to give stability and continuity to a society which was in constant danger of flux

The site of the original excavation, which is in the Palestinian Authority, can still be visited. The trenches dug in the 1950s are open and plainly visible. There are walkways over the site. You can even fly over it by cable.

Creating an Ancestor: the Jericho Skull is in Room 3 of the British Museum from 15 December. It is free to visit.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks