The American Dream: Pop to the Present, British Museum: Why are we wasting valuable time with pop art?

The British Museum is staging a blockbuster ‘The American Dream: Pop to the Present’, but why does the scholarly institution want to demean itself by using pop art as a selling point

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

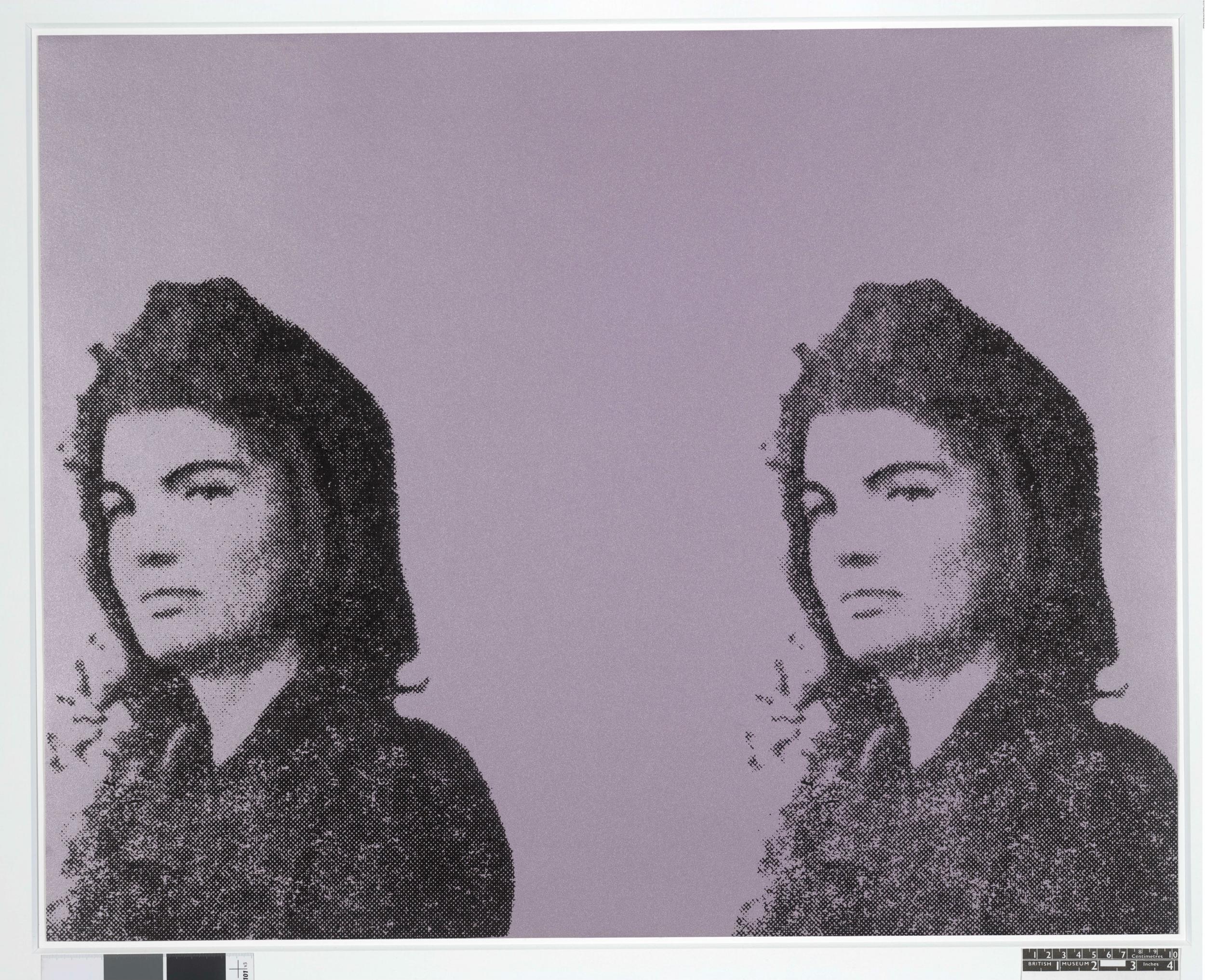

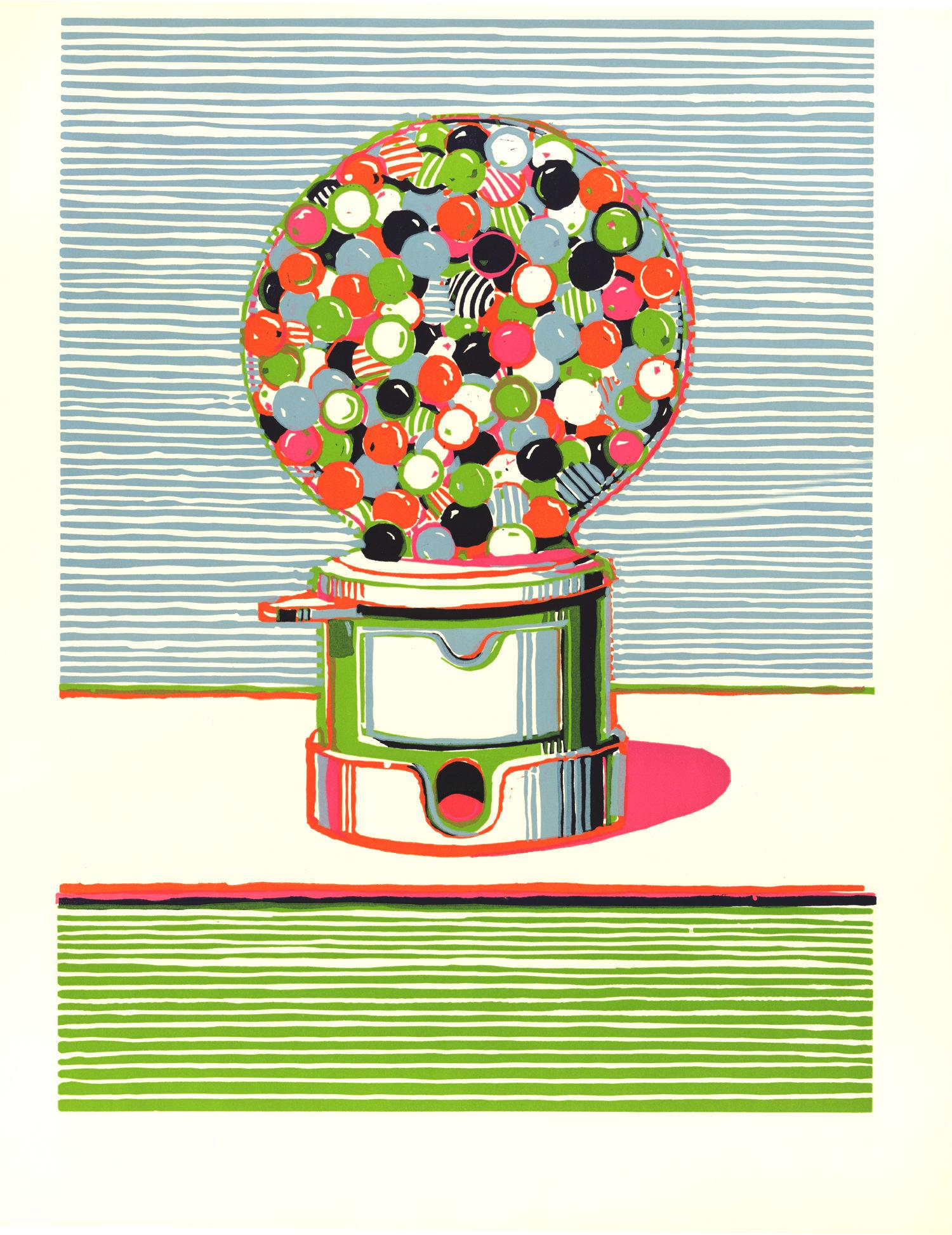

Your support makes all the difference.Is it some kind of a joke? Can the new show at the British Museum, really be called The American Dream: Pop to the Present? What do a rabbit and a cabbage have in common? Surely pop art represents the triumph of superficiality, the death of profundity and careful looking. Rather than being some kind of coy critique of commodification as its bone-headed cheerleaders are often inclined to argue, it is in fact an acceptance that commodification is king. What, then, is the British Museum, that bastion of careful, scholarly scrutiny, doing warmly embracing and collecting such rubbish? I’m aware that the show surveys more than pop art – but the fact is that the British Museum has chosen to draw attention to pop in this way as a selling point.

Or is it the crowd-pleasing, crowd-pulling title of the show that really matters? If that is the case, there's an even bigger question to be asked. Why do big art institutions stage ever larger and larger shows? The entire exercise is ridiculously self-defeating. Generally speaking, the bigger the blockbuster, the more unsatisfactory the viewing experience. Remember Van Gogh or Monet at the Royal Academy, or Gauguin at Tate Modern, how you got squeezed and pushed aside just as the painting you were most hoping to see hoved into view?

What exactly is at work here? Is it more than just money? Or, to put it slightly less surrealistically, can there ever be a notion of perfect fit when it comes to a great museum and the exhibitions it chooses to mount within its walls? Or ought a blockbusting crowd-puller – like someone too famous for his or her own good – be allowed to shoulder its way into anywhere it might choose to go? Would its swaggery, overbearing presence be that irresistible?

There are two kinds of gallery in the world. The first is a glorified empty shed – or a kunsthalle – waiting to be filled. This kind of institution lacks a permanent collection. It needs things to hang on its walls in order it to breathe life into it. The Royal Academy belongs to this category. Needless to say, the exhibitions in such places have to change regularly because people don't keep coming back to look at the same thing.

The other kind – the British Museum belongs to this second category – is full to the brim with what it owns already. And its collections are of an unparalleled depth and richness. Think of the Louvre and the Hermitage. And then, slightly awkwardly, there is a third kind, which falls somewhere between those two categories, and it is an institution which most certainly owns a permanent collection, but that collection, while wishing to tell art's story to a greater or lesser degree, is full of embarrassing holes because of the lukewarm and inconsistent way it may in the past have gone about acquiring what it currently owns. That certainly was the case with Tate Modern when it first opened in 2000. (Less so now.) So you need to stage temporary shows in order to disguise the fact that you are not quite telling enough of the story of contemporary art in the rest of the building.

Is there really a place for a blockbuster in the British Museum though? The word itself grates on the ear, doesn’t it? There is something unlovely about the word block. It hits you like a brick to the back of the head when you were least expecting it. Extend it a bit then, by a syllable or a few letters perhaps, into blockish, blockhead or blockbuster. Does that help? Not really. The malodorous galumphingness is still there. It still doesn't quite sound like a trusted family friend with coins in his pocket on a Friday night.

Perhaps a blockbuster is an undesirable thing in itself then. Several custodians of the world's greatest museums are of this opinion, as it happens. Two conversations spring to mind in particular, one which took place some years ago in the office of Mikhail Piotrovsky, director of the Hermitage in St Petersburg, on a winter's afternoon, when the sun was lighting up the gilded spire of the St Peter and St Paul Fortress on the far bank of the Neva. The other, with Dr James Bradburne, the Director General of the Brera in Milan, was more recent, and it happened on an autumn evening during Frieze Week at the Athenaeum in London in the autumn of last year.

The issue under discussion was the same one: the suitability and the general desirability of blockbusters. Piotrovsky has never had time for them. Nor did his father before him (the Piotrovsky dynasty has been in charge at the Hermitage since the 1960s). He just does not see the point - and he has a very good point when he says that he does not see the point. To stage a blockbuster inside the walls of the Hermitage would be ridiculous for two quite separate reasons. First of all, it would needlessly distract attention from the museum's own great collections. Visitors come to St Petersburg to see the several million objects it is known to contain, and whose existence it exists to celebrate, from the eighteenth century onwards. The buildings themselves, that fantastical, high-baroque iced cake in green and gold, are a part of its allure. Why then stage a distracting side show by shipping in excrescences from elsewhere? Why waste money by drawing greedy eyes away from the main event?

James Bradburne looked bemused too when I asked him about temporary exhibitions at the Brera. We don't do exhibitions, he told me. We do inhibitions, which is a much more scholarly and interesting way of drawing attention to what we already have. He mentioned a loan of a single painting from elsewhere which threw interesting light on a painting by the same artist that the Brera already owned. The challenge, he went on, is to get the public to see the marvels that the Brera already possesses, but to have its eyesight cleansed by coming at them in a slightly different way; not to bring the outside in, but to enrich the experience of seeing what the public may thinks it knows all too well.

So these are the questions that the British Museum needs to ask itself this week. What on earth is it doing staging a show which seems to run so counter to its strengths as one of the world’s great bastions of scholarship? Is not pop art the near perfect embodiment of everything that is most silly, most trivial and most dispensable? And if that is the case, why would the British Museum choose to demean itself by by regarding it as a subject worthy to take up valuable exhibition space in its galleries?

The problem with the British Museum is that it does not do enough to draw attention to the richness of its own great holdings. The gallery now regularly sponsored by Asahi Shimbun, that great Japanese daily, is a move in the right direction, in which a single object is the centre of scholarly attention. How could anyone forget the marvellous little show which recently contextualised the Meroe head of Augustus Caesar, with its extraordinary, all-seeing glass eyes? That piece has now, fittingly enough, melted back into the collections.

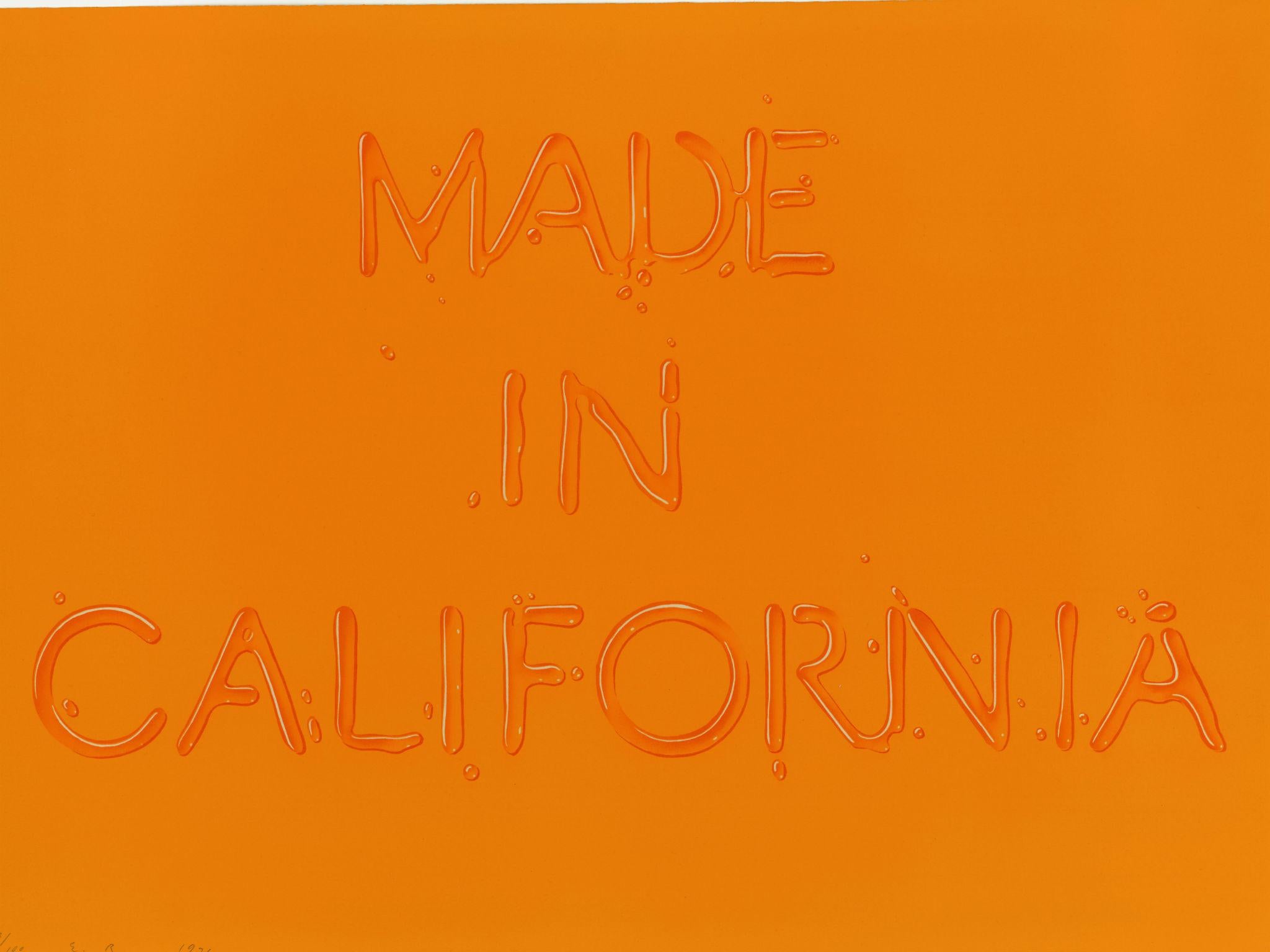

How well do we know the magnificent Assyrian lion hunt frieze in those rooms which are so breathingly close to the Elgin Marbles? How is it that so few visit those friezes, so breathtakingly modern in their ancientness? Instead, we are being invited to the Sainsbury Galleries, where we can waste valuable time having our attention drawn to a second-rate print of a gas station in a desert. Man’s folly is boundless.

'The American Dream: Pop to the Present' is at the British Museum from 9 March to 18 June 2017

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments