Steve Lazarides interview: The man behind Banksy is bringing graffiti art to the gallery

Call it street art, guerrilla art, or neo-graffiti, it's not the sort of stuff that should ever end up in a gallery, right? But that's exactly where Steve Lazarides has put it – to spectacular effect. And, as the man behind Banksy tells Susie Mesure, his critics can go hang

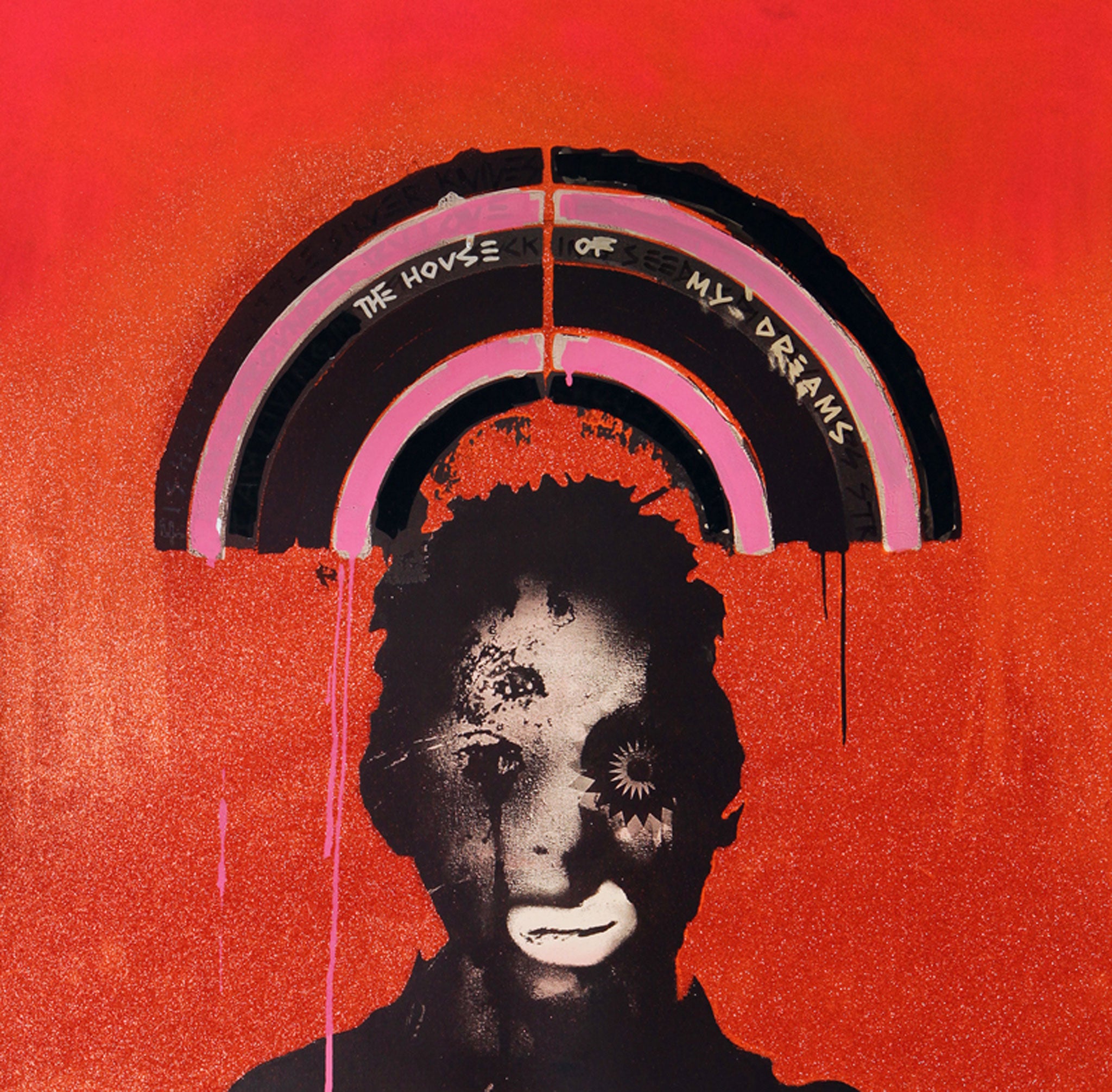

There is nothing subtle about the image that hits visitors stepping into the Lazarides Rathbone gallery just off Oxford Street. It depicts a black man, in a monochrome print, locking you into a stare before your eyes shift to the object he is brandishing. "That's probably one of my favourite pieces," says Steve Lazarides, a smile breaking out across his lean face. "You can tell people's attitudes to prejudice very quickly with that one. They go, 'Jesus! He's holding a gun!' And you go, 'Nah! It's a camera'."

For Lazarides, who is walking me through the Fitzrovia townhouse showcasing his tenth-anniversary exhibition, the piece, by the French photographer JR, is a useful lesson in not stereotyping. Lazarides is particularly sick of people typecasting the likes of JR as street artists, which is possibly a bit rich. JR might have made his name tagging Parisian streets, but Lazarides made his own by championing his work, along with that of other "street" artists, in his gallery.

Of those, none stands out more than Banksy, the graffiti legend whom Lazarides, who is 46, fell into representing in the late 1990s, long before anyone had dreamt that street art might become a thing that merited serious consideration, let alone being displayed in a gallery. Although the pair, both from Bristol, parted company nearly nine years ago, Lazarides knows he will forever be known as Banksy's ex-gallerist. "I'm past caring," his suited shoulders shrug from the sofa where he is sitting on the top floor of the gallery. "When we split up, I can remember to this day the conversation I had with him: 'We could live to be 150 and we're still going to get stuck in the same sentence.'"

The detail of the duo's falling out remains a mystery but there seems to be no love lost on either side. "I saw him at a Massive Attack gig last Friday, but maintained a healthy distance," Lazarides says. Seven Banksy pieces, including Gangsta Rat and Toxic Mary prints from Lazarides's own collection, hang on the second-floor walls, along with works by Oliver Jeffers, Sickboy, and Scott Campbell. Together they comprise "Still Here", the provocatively titled show that marks a decade of Lazarides the gallerist, and yes, he says, it is a "little bit of a fuck-you" at the rest of the art world.

"It's a miracle that we are still here," he grins. "Every step of the way we were told by the art world that what we were doing was impossible, and it would never work. But you know, we're still here." By "it", he means rehoming art from the streets in a gallery, for all that he grimaces at calling the men – and women, but mostly men, "I have no idea why" – he represents "street artists".

The son of a Greek-Cypriot kebab > shop owner and an English mother, Lazarides ("Laz" to his mates) can play the non-conformist because he is one. Growing up, art for him only existed on the outside of buildings. Showing me around the exhibition, he pauses at some canvases by Robert "3D" Del Naja, the Massive Attack singer-cum-graffiti artist. "He's really the reason I got started. I used to get the bus in from the estate I lived in to go and see his graffiti. Way before he started his idiotic pop band!" Later, chatting by telephone, he tells me that one of his friends was a "kid called Inkie", another of the Bristol graffiti alumni. They used to hang out in the 1980s at Barton Hill boys' club, now a boxing club. "It felt like a community; we were kids from humble backgrounds and this belonged to us. These guys were going out and making rough places pretty."

And now, those guys are making a living because people are splashing serious cash on their work: fans include Brad Pitt and Christina Aguilera. Fellow gallerist Oliver Cox, who owns west London's Graffik, says street artists owe their popularity to Lazarides, who gave them a "platform to exhibit commercial works". Cox calls Lazarides's contribution to the scene "immense", adding: "He pioneers artists in the early stages of their careers, Banksy being just one example, which shows what a great eye he has for emerging talent." And – Banksy aside – they are grateful. Jonathan Yeo, the portrait painter, calls Lazarides the "most influential figure in the street art movement" after Banksy. Lucy McLauchlan, whose work features in "Still Here", says Lazarides encouraged "adventure and freedom – much needed when you're trying to make sense of collating 'street' works into an indoor exhibition space". The upshot, adds 3D, is that "art's no longer the preserve of the middle class and the wealthy".

When I arrive, Lazarides is cleaning himself up after being turned into a piece of art for the photo shoot. It reminds him of his former life as a photographer. "I shot a bunch of people for The Independent magazine. It was the biggest commission you could get." He blagged his way on to a photography course, passing off his friend's dad's amateur portfolio ("it was as shit as you could possibly get, all half-clad women") as his own. "I recently saw the guy who interviewed me, and he said the only reason they took me on was because they figured anyone who was willing to lie that badly was willing to work really hard."

He was the picture editor for the magazine Sleazenation when he met Banksy, and started selling his prints from the back of his car. "I've always called myself the accidental art dealer because this isn't really what I ever planned on doing. But I had a driving ambition to show people that you can do things differently. I want people to think that you don't have to be a lord or a lady to open up a gallery. That elitist nature [of the art world] puts so many people off. This is supposed to be a fun experience. It's art, for fuck's sake. Not oil, guns, or diamonds."

Art world rants aside ("Don't get me started on Frieze [the art fair]. I hate Frieze. It's a tent. In a park. That sells art. Not a cultural phenomenon."), Lazarides is way less grumpy than I'd expected from his social media tirades. He is "anti-dog shit"– who isn't? – and "anti-prejudice", hence his passion for JR's work. And, naturally, isn't keen on being pigeonholed. "We always get pegged as being a street art gallery and we never were, it's just that we represented the very best of what was out there. At the same time, we had Jonathan Yeo and Antony Micallef, so it was always a mixture of painters and street artists. It was more a mindset than anything else. A lot of them had been shunned by the traditional art world and come into it their own way."

Lazarides, who is wearing a slick suit and silk camouflage shirt, thinks the epithet risks trivialising the art. "I get sick of seeing the 'street art' tag in brackets next to artists like JR. These guys are just artists. They don't need to be ghettoised." And yet even Lazarides "sticks with the street art thing, because it's easy" despite preferring "contemporary art". He adds: "I think 'street art' was a term used by the art world to make it feel like it was children's art." There is certainly nothing infantile about the prices street artists can fetch. Banksy's Keep It Spotless, a collaboration with Damien Hirst, holds the record with a whopping $1.9m (£1.6m) in 2008. And an urban art sale by Bonhams last year raised some £750,000.

It's the day of the pre-opening party and Bob Marley is blasting out during an > extended soundcheck. Never one to miss an excuse for a bash, it's also the morning after the pre-pre-opening party Lazarides decided to throw when he learnt that there were no fewer than 1,000-plus people on tonight's guest list. No longer a "mad party kid", ditching the booze means he is spritely and fresh-faced, splattering me with his opinions much as the Italian Miaz Brothers splatter their canvases with spray paint. For all that his reputation is as a self-promoting "chancer" – to quote friend and collector, the chef Tom Kerridge – he is discreet about the previous evening's revellers. He omits to brag that Janet Jackson was there, something the tabloids reveal. The singer is married to the genre's latest and greatest acolyte: the Qatari billionaire Wissam Al Mana. The fashion tycoon recently bought a stake in the gallery.

Lazarides strokes his head for the umpteenth time, electric with nervous energy. "I've amazingly found an investor. It's a good story. He turned up one Monday, and we're closed on Mondays so my young assistant came upstairs and was like, 'This guy's just been here but I've sent him away.' I'm like, 'Why are you up here?' And he's like, 'Well, he gave me his card, and he seems to be a Qatari billionaire.' So I phoned him back and he came in. Things got very, very tight. I'd always wanted to expand the business; I could only get it to a certain level on my own. So I sent him a cheeky email, 'Do you fancy investing?' and he was like, 'Send me your books'." Lazarides calls them "the odd couple": the tycoon and the "kid from quite a humble background", but insists they have a "similar mindset".

If a Gulf Arab investor and a mooted move west to Mayfair jars with the cultivated edgy vibe of a man who represents outsiders, well, Lazarides isn't bothered. He reckons the cash injection and new address will help buyers take his artists seriously. "These guys deserve to be seen properly; unfortunately that's seen as success by quite a lot of people." Plus moving to the "heartland of contemporary art", as the Art Fund describes Mayfair, means he can play the maverick card from within the establishment. "I want to shake it up! It's so boring. Places like Cork Street have been dying on their ass for years," he adds in his soft West Country burr, his hands gesticulating wildly.

Is this the end, then, of street artists? The end of the "outsiders living in a parallel art world outside the mainstream", as he once called them? Or of what critic Jonathan Jones, a 2009 Turner Prize judge, sniffed was more about celebrating "ignorance and aggression" than anything "aesthetic"? Lazarides counters: "A lot of these guys haven't been outsiders for some time. It's my job to grow with them and take them up as far as we possibly can, as well as try and encourage young artists to come through. And," he grins lest I take him too seriously, "to annoy the art world. Mainly to annoy the art world."

Back on my tour, an oil of several thousand birds by Xenz, otherwise known as Hull's Graeme Brusby, offers an unlikely glimpse into Lazarides's private life. "My hobby, that no one believes I do, is bird watching. I was not the most easy of children; I'd go out into the woods, and just be there on my own to get away from everyone. I'm not a mad twitcher; don't care what I see, sparrows, starlings, or a dodo."

This segues into another disclosure: he's a keen allotmenteer. "I need something to come down from this. I don't drink any more so gardening is what it is. My grandad got me into it." His plot is in Dulwich, near where he lives in south London, with his wife, Susana, a fashion designer for Asos. They have been married for more than 20 years and have three sons: "Eight-year-old twins and a 10-year-old, so it's a busy house." He tries not to talk about them, but can't help himself. "One of the twins is really good [at art] and keeps giving me bits of paper that he's signed to go in the gallery."

Although Banksy exploded the market for street art, Lazarides frets that it remains off the radar for museum curators. He is bitter that that Tate Modern, which allowed six street artists including JR, Os Gêmeos and Blu, to paste their creations on the outside of its Bankside building in 2008, didn't add their work to its permanent collection. And that, he says, was despite him offering to donate pieces. "They refused to take them. What, their art's not good enough to come in?" He fumes. "It's because they didn't discover it. But surely if you're shaping what the future will think of today's art, you have a remit to take ALL art that is powerful at the time? And this is probably one of the most powerful movements in the last 40 years. You had the YBAs, which was great, I love Damien [Hirst]. But my honest opinion is that [the street art] movement has reached way more people and touched way more lives." For its part, a Tate spokesman said, "We cannot find any record of a formal offer being proposed."

In London, street art is now in the "vanguard of gentrification", with property developers "openly asking" for the tag of graffiti approval to boost prices. "People are fighting to keep a good piece, whereas before, you'd be lucky if it wasn't painted over in four hours. There isn't much new talent coming through in London though. I hate to say it, but I think a lot of the guys working on the street are doing it with an eye to being picked up commercially." Elsewhere, "the Brazilians are killing it: Os Gêmeos, Nina Pandolfo, Finok. And Russian society is incredibly creative."

For someone who makes his living selling art, Lazarides makes a lousy salesman. "It's like my mum always said. Do you like it or not like it? If you like it, buy it. If you don't, don't." Tom Kerridge liked a £22,500 painting by the French artist Zevs (featuring his trademark "dripping" corporate logo on a Hockney-esque Californian scene) enough to part with the cash. "I can't afford a Hockney, so what better than a street artist who has defaced a Hockney replica?" Kerridge tells me.

Lazarides himself has plenty to say: on politics (he rated Ed Miliband but Corbyn is a "fucking nutter"); on whether kids belong in galleries – "Hell, yeah! It doesn't have to be silent for you to take meaning from the paintings" – and on the latest art-market bubble. "Warhols can't keep going for £40, 50, 70 million for a painting that has no intrinsic value. It's a piece of canvas, four bits of wood and some household paint."

That almost counts as a rant. As does his antipathy towards prejudice. "You ask me why I get annoyed about things? It's because this art is populist. But not because it's bad. Populism isn't always bad. Sometimes it's populist because people actually like it." And if they happen to be billionaire Qatari investors, or Mayfair shoppers, so much the better.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks