Squaring the ancient and the modern: The art of Giorgio de Chirico

Claudia Pritchard hails the warped classicism of artist Giorgio de Chirico

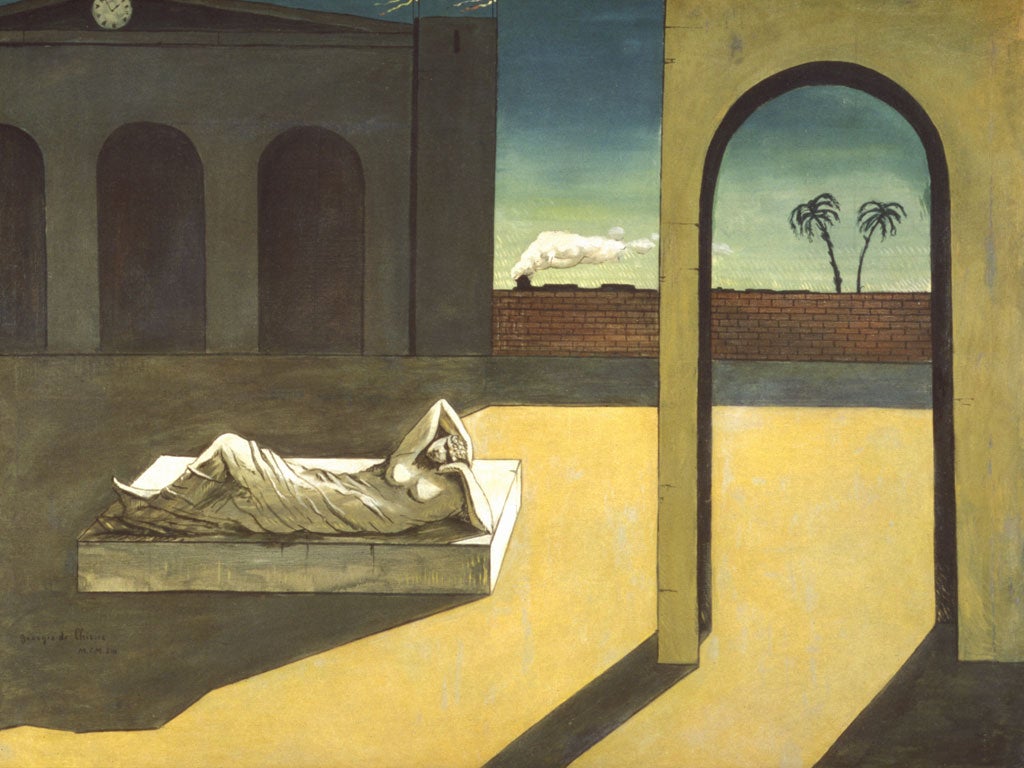

Between the lengthening shadows of a deserted town square in the afternoon reclines a classical figure, neither human nor merely an object. Feminine and fluid, it lolls towards the viewer on its plinth, one massive knee cocked under the tumbling folds of a long robe, the upper arm tucked over the head, the other supporting an appreciable weight. The Soothsayer’s Recompense, painted in 1913, is distinctively the work of Giorgio de Chirico, one of the Piazze d’Italia series that forged a new visual language, parsing modernity with classicism.

On closer inspection, the scene is not all it seems. The perspective, apparently true to life, is actually contradictory, with several vanishing points, rather than a single one. Light pours in through an archway too slender to support itself, and huge areas are plunged into shadow, while the clock stands at only ten to two, when the sun is still high. No surprise, then, perhaps, that the same artist would, in time, make his classical figures – here, Ariadne, waiting for Dionysus, but it could have been one of many characters from classical mythology – step out of the picture and on to the gallery floor.

De Chirico was born in 1888 to Italian parents in Greece, at Volos, the port from which, in Greek mythology, Jason and the Argonauts set sail on their quest for the Golden Fleece. Growing up largely in Italy after the early death of his father, a railway engineer whose work had kept his family on the move, the artist relished the duality of his classical background, and his invented Italian squares were based in part on the Piazza Santa Croce in Florence with its colonnades, deep recesses and shafts of sun between slabs of impenetrable shade. The squares represent probably the most praised period in his long career, and their success was, not least, commercial.

Years after they were painted, de Chirico would hint, in a conversation in the 1950s with Eric Estorick, founder of the collection where Giorgio de Chirico: Myth and Mystery opens shortly for three months, that he was not above supplying a hungry market. “If they want those, I’ll give them those,” was the gist of his admission, and, says director of the Estorick Dr Roberta Cremoncini, he was not above creatively re-dating work, either: “He was very shrewd. Possibly not a very nice person.”

Like so many artists, de Chirico was drawn to Paris at the beginning of the 20th century, but he did not fit in with the Picasso and Braque crowd and was more attracted to the theories of Nietzsche and to exploring the world of the subconscious. While the Paris set was flattening the image in its Cubist still lifes, de Chirico, drawing on antiquity, was creating invented spaces of almost giddying perspective. From around 1910 to 1914 the city squares became increasingly dream-like, dotted with the apparently unconnected and out-of-scale objects that delighted the early Surrealists, who later boycotted a de Chirico show when he reverted to a more classical style. Giant fruit and vegetables or a single glove got into the picture, while, as in The Soothsayer’s Recompense, a steam train often puffed by in the background. In many cases there were more logical explanations for his subjects than appeared at first glance, so the steam train that chugs along on the horizon is a reference to de Chirico’s dead father, while the sails that bob up in the far distance hint at Volos and Jason’s quest. Meanwhile both train and boat may suggest his own preparedness to travel into the inner mind.

The remarkable sculptures that walked out of the Piazze d’Italia are at the heart of Myth and Mystery, revealing a side of the artist that is often overlooked. De Chirico began sculpting in the 1960s, when he was in his seventies: one of the most striking pieces in the show, Disquieting Muses, was made in the year of his 80th birthday, and its mirror-smooth finish is typical of this work. De Chirico favoured silvered or gilded bronze, which produced a dazzling, almost gaudy lustre. Disquieting Muses has the featureless mannequin heads that are a feature of the paintings, classical allusions in the graceful folds of Hellenic drapery, architectural references and a mask-like shield. But de Chirico instils in these apparently faceless automatons a touching humanity by giving the standing figure a modest tilt of the head, and the seated one a head that is too tiny and a hollow in the torso, suggesting vulnerability.

While many such sculptures stand only a few centimetres high, Il Gran Metafisico (undated) towers over the viewer, dominating the room. De Chirico, who wrote prolifically about his theories of art, had firm views about the relationship between artwork, viewer and gallery. He observed that we relate differently to statues, depending on whether they are placed on the façade of or on top of a building, or in a public space where, as he wrote in 1927, they seem “to merge into the swirling of the crowd and of everyday town life”. “In a museum a statue looks different, and in it is its phantom appearance that strikes us, an appearance like that of people suddenly noticed in a room we had at first thought to be empty.”

The ambiguity of the inanimate object made to represent a living thing also intrigued him. “As regards the mannequin,” he wrote in 1942, “the more human it looks, the colder and more unpleasant it becomes. The mannequin is disagreeable to our eyes because it is a sort of parody of a human being … A statue does not aspire to life ….” Thus, his eyeless, quizzical heads and pedimented torsos are easier to relate to than the shop dummy with its waspish waist and staring eyes.

De Chirico believed the sculptor was like a water diviner, detecting and drawing out that which is already there. “What will emerge is already inside, asleep; like the marmot in its burrow, during the winter months,” he wrote in 1940. “It is all a matter of knowing where to begin, what bells to shake to awaken the sleeping animal.”

‘Giorgio de Chirico: Myth and Mystery’ is at the Estorick Collection from 15 Jan to 19 Apr 2014 (www.estorickcollection.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks