Sex, death and violence: how do you explain great art to little children?

A new book aims to help parents and children deal with the sometimes alarming imagery in our galleries. A mother (and her daughter) give it a test drive

In the list of things bound to make a middle-class person shudder, failing to enjoy taking your child to art galleries ranks pretty high. But a gallery presents opportunities for a child to ask awkward questions like nowhere else, and who seriously wants to be the adult in charge when that clear fluting voice pipes up in the echoing silence of Tate Britain? Even the sort of charming and reasonable questions that pop up in Susie Hodge’s new book Why is Art Full of Naked People? can become tongue-tyingly awful to the average, bashful Brit, but in real life the questions are neither charming nor particularly reasonable.

My daughter, about to turn seven, is admittedly just outside the age range for which this book has been written, but as she’s unlikely to undergo a transformation in the next month, I suspect she’s already pretty much like a seven-year-old. Consequently, her interests in art, as in life, revolve around the cute (preferably of the four-legged variety), the naked (inviting minutely observed, loudly voiced comparisons with her parents), and existential and religious questions informed by a shaky understanding of Christian doctrine.

Death, so ever-present in art, is a fascinating topic for a seven-year-old, and presents particular challenges in the period following Easter

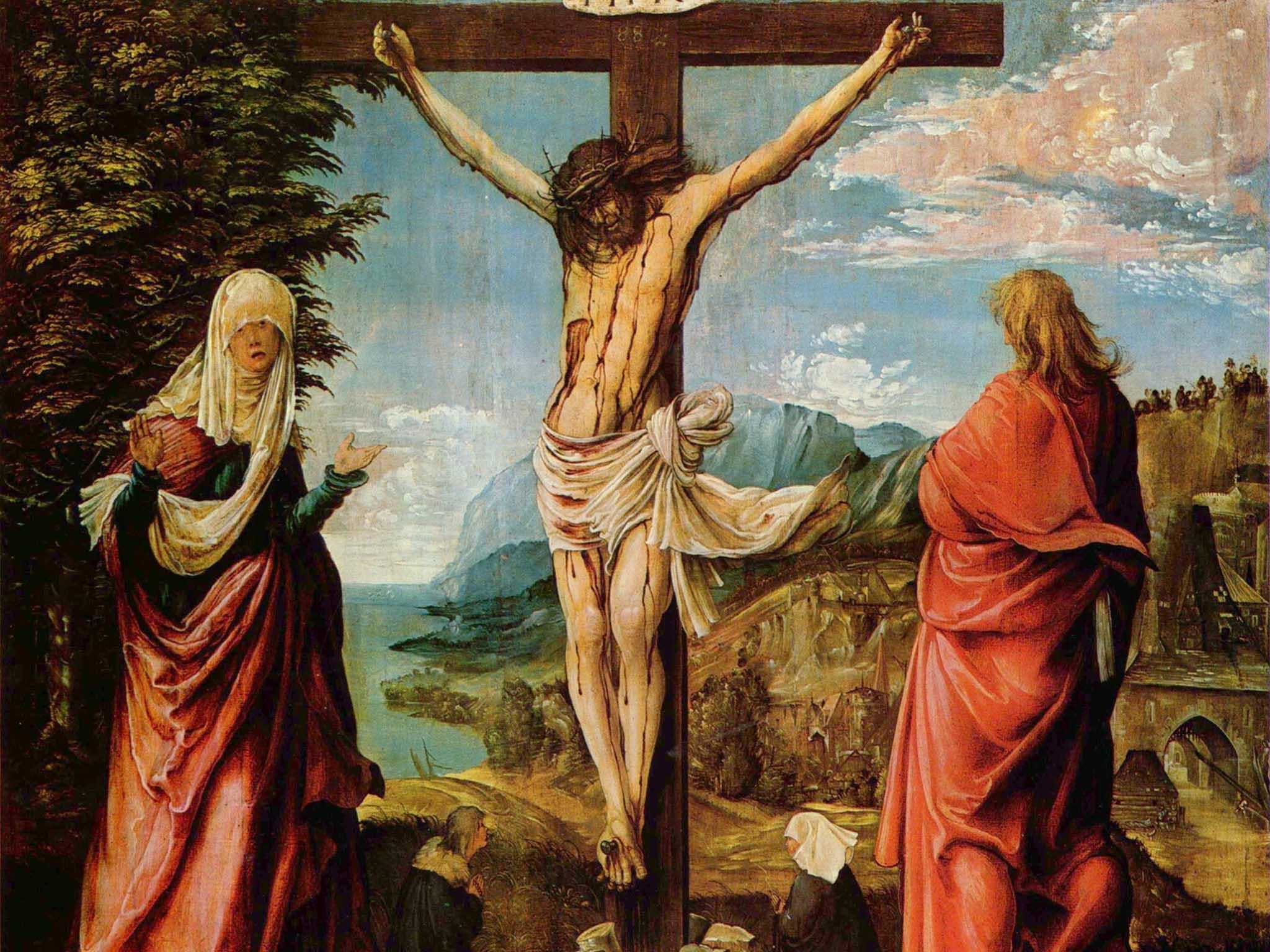

Sometimes these interests collide in unexpected ways, so that an 18th-century French confection featuring a little girl holding a kitten, which ticks all the boxes in terms of cuteness, also prompts concern for the welfare of the cat now, with “is the cat still alive?”, followed inevitably by, “how did it die?”. Death, so ever-present in art, is a fascinating topic for a seven-year-old, and presents particular challenges in the period following Easter. My daughter’s school did so well at avoiding the gory aspects of crucifixion, they made it sound a positively good option, so that a Renaissance altarpiece inspired the unanswerable: “Can you ask to be crucified?”

The hypothetical child at the heart of Hodge’s book has, in comparison, an enviable breadth of interest that seems rather sanitised, avoiding references to death and bodily functions, and keeping the book on the straight and narrow of what art means and why it is like it is. The answer to “what’s with all the fruit?” effortlessly encapsulates many essential points about still life painting, even introducing the role of photography in the burgeoning modernism of Cézanne’s Apples and Oranges (1899). A bubble at the edge of the page asks, “who else painted lots of viewpoints all at once?”, intuitively guiding the reader to a section on cubism, so that a wide range of topics are covered with admirable economy. The question bubbles recur throughout the book, encouraging a child to dip in as the mood takes them, and helping to stimulate and support their thinking.

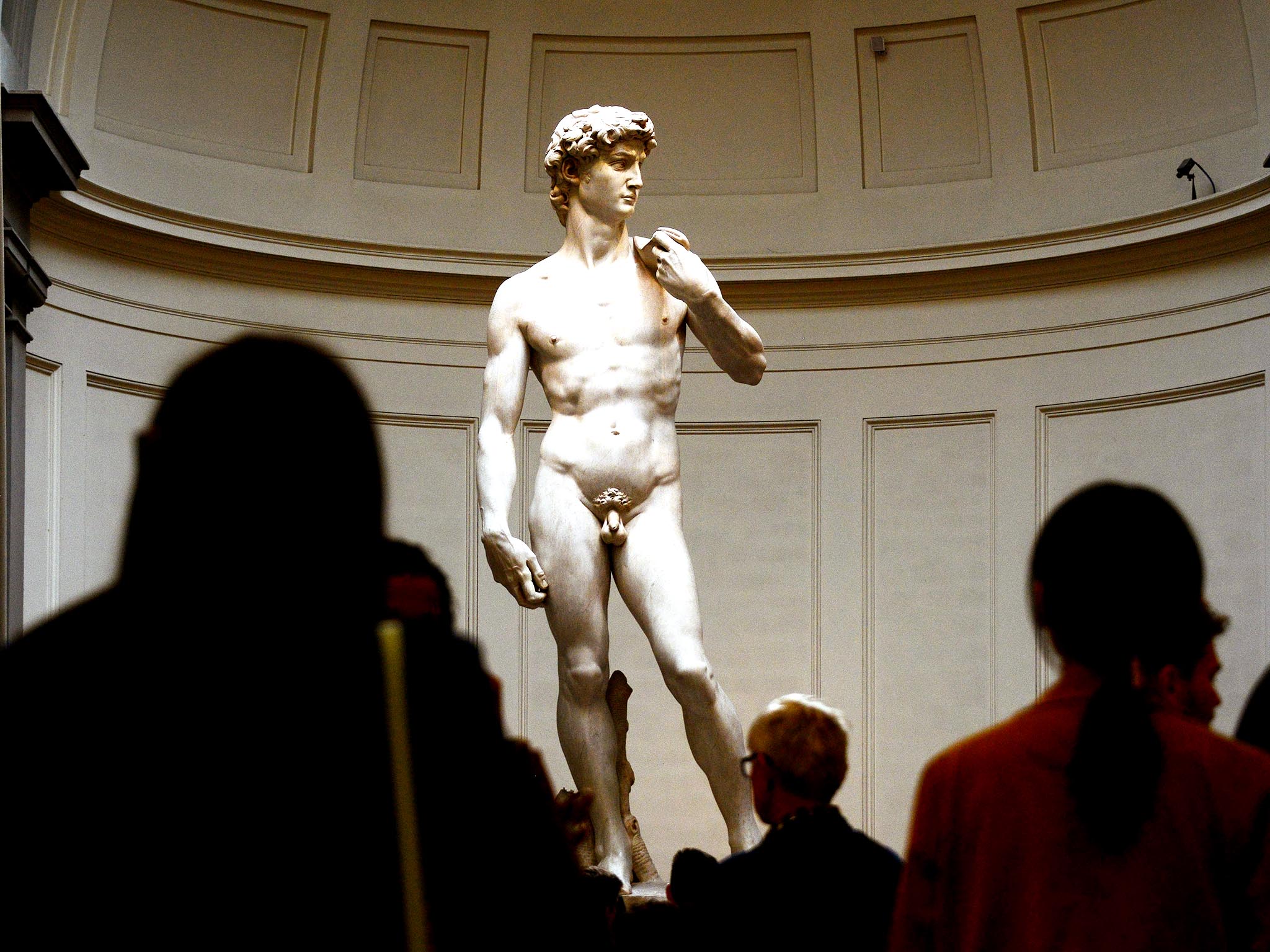

Some sections are more successful than others, and Hodge’s response to the book’s titular question may not entirely satisfy the toilet humour of your average seven-year-old. The explanation, that “it all started with the ancient Greeks who thought that the naked body was beautiful and should be studied”, seems likely to elicit only a “who?” followed by a “yuck!”.

The overall tone is fun, if a little breathless because of the peppering of exclamation marks. With its jolly illustrations and engaging design, beautifully printed on good paper, this is a book that will sit as happily on a coffee table as a child’s bookcase.

An aspirational tool somewhat in the mould of the Boden catalogue, this book serves as a good-humoured reminder of the kind of civilised person one might coax into being if only trips to the National Gallery were less arduous. The author, it seems, is sympathetic, and of all the improving and thoughtful questions posed, “why do I have to be quiet in a gallery?” is surely Hodge’s conspiratorial wink to every long-suffering adult. The answer – “Ssh! Be quiet! The artworks are talking” – is one that will be treasured and trotted out by parents up and down the land.

‘Why is Art Full of Naked People? And Other Vital Questions About Art’ by Susie Hodge (Thames & Hudson, £12.95) is published on 1 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks