Sara Shamma's 'World Civil War Portraits': Painting a nation's nightmare

The Syrian artist tells Simon Tait about the fear and fury that shaped her disturbing new work

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Hanging in the private office in Damascus of Asma al-Assad, the wife of the President of Syria, is a portrait of her commissioned in 2011 from one of her country's leading young painters. "I will never paint a picture like that again," says the artist, Sara Shamma. "That Syria will never exist again, and I am a different painter now".

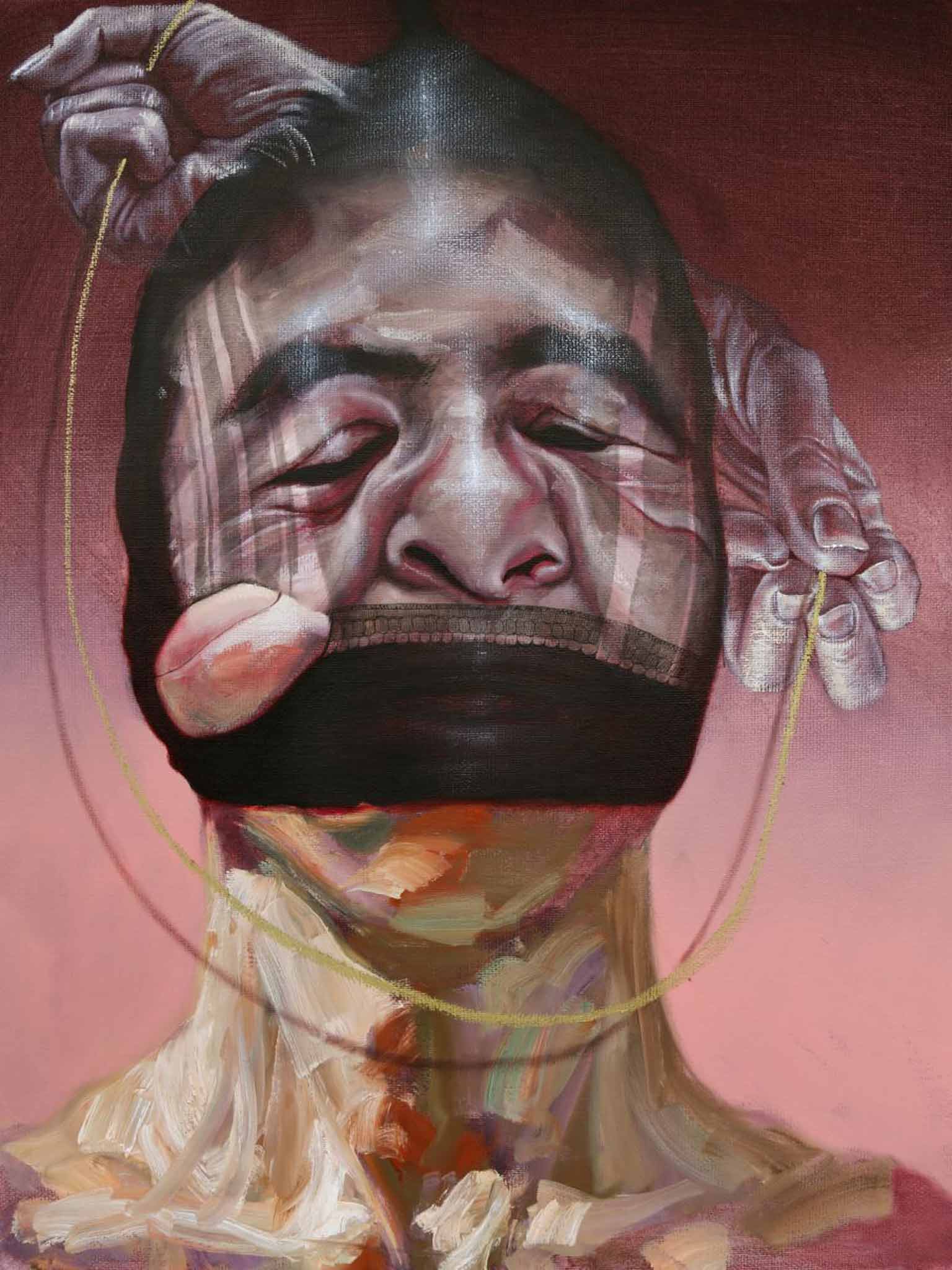

Now, Shamma paints the visceral nightmare of the Middle East that she sees spreading across the world: men and women trapped in graves; faces distorted by laddered stockings as a garrotte hovers; a man suspended hand and foot by chains, like the butchered bull behind; another trapped and taunted by the kidney that is the subject of an enormous illicit and murderous trade; another eating his own foot.

Her exhibition of 15 new paintings opening at Truman's Brewery in London on Friday is called World Civil War Portraits, though it's more a collective portrait of a phenomenon that started for her as a local crisis and has grown into a global catastrophe and a fear that dominates her.

In November 2012 Shamma was in her comfortable suburban home in Damascus with her children, waiting for a car to take her to her studio – a 10-minute walk normally, but by then a complicated one-and-a-half hour drive. Just as she leaned forward to kiss her two-year-old son, Amir, a car bomb exploded outside her door, leaving them unharmed but shattering glass and their Syrian lives for ever. As soon as roads were open, she fled with Amir and the baby Amal to Lebanon. She will never return, though her husband, Mounzer Nassa, continues to work in Syria organising UN food aid convoys.

"The human spirit has died in Syria, and it is dying elsewhere now," she says, turning to the shock of the Charlie Hebdo assassinations in January. "Those are French citizens doing this, not Arab insurgents," she says in her uncertain English. "I feel the fear now wherever I go".

She says she paints from her unconscious. There is allegory in most of the images, with ghosts and shadows lurking and menacing. She doesn't know what will happen when she starts to paint. Shamma, now 40 and the daughter of a civil engineer and a child psychologist, went to art school in Damascus and was part of a nascent but flourishing movement through the 1990s and early 2000s, during which time she built an international reputation.

In 2004 she was fourth in the BP Portrait Award, with a self-portrait made with barely perceptible brush strokes; it was more than competent, but unremarkable. By contrast, most of her new paintings, all done in the past nine months, are furious, with huge sweeping brush strokes carving out the shapes of her fury on large canvases.

Eyes are mostly blue because they are more expressive of the fear and anger she feels. The face of the man whose features are smeared inside a tattered stocking, Incognito 1, was done entirely from her imagination, as most of them are; it started as an exercise in figurative painting but became a garrotting: except that the hands holding the ligature are both right hands, one a fist gripping the rope, the other gently guiding it with fingertips.

"I like painting to give me very different facts, like the dream," she says. "I want it to take me to another world. I don't want the painting to describe something real. Sometimes it takes me to a horrible place, but I don't feel that when I'm painting."

She uses photographs and often takes her camera to a local butcher's shop for images of carcases, skeletons and organs. The viscera symbolise the shameless inhumanity of the war and contrast it with the normality that humans strive to recapture. So, in Butcher, a huge cow's liver is seen next to a tall figure, a benign-looking woman. She is actually the butcher (so sensitive to the task of killing the animals in the halal way, Shamma says, that she feels physically sick at having to perform the act); but, from closer up, the brush strokes that make up her face show the panic, anger and hopelessness that haunts all Shamma's faces.

In her self-portrait she caresses a human skull, a grotesque affection for the lost past; behind her is a set of bones forming a throne, the actual skeleton of a gorilla; in front is her daughter's semi-inflated pink balloon, an intimation of life continuing.

Many in the Syrian art diaspora are finding it impossible to paint, unable to adapt to life in Lebanon, Dubai or wherever they have escaped to. Shamma says they have to forget the old Syria and move on, as she has.

"The whole country now is destroyed. The people are destroyed as well; their mentality is destroyed. I think the culture is destroyed," she says. But there is hope. In a delightful portrait of her son she has got him to make his own drawing, on one half of the face, of what he was thinking as the portrait was being made; it could hardly be more affectionately intimate.

"Maybe it can be built again, I don't know," she says of the Syrian art scene, "but it will have to evolve in another way. The Syria we knew is gone."

World Civil War Portraits is presented by StolenSpace at The Old Truman Brewery, 91 Brick Lane, London E1 (020 7770 6000), to 24 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments