Rubens and His Legacy, from Van Dyck to Cézanne: Stunning works make the flesh crawl

17th Century painter is famous for his luminescent, voluptuous female nudes

I am currently reading Ordeal, the autobiography of Linda Lovelace, star of the 1972 porn film Deep Throat. The book describes how she was hypnotised by her pimp husband in order to perform acts that would define her as the muse of the modern porn industry. With this in mind, I visited the new exhibition Rubens and His Legacy: Van Dyck to Cézanne at the Royal Academy, London.

The 17th-century Flemish baroque painter is most famous for his luminescent female nudes, notable for their voluptuousness – their weight – by contrast to today’s standards of famished ideal beauty. Their skin is tender and creamy pale, seemingly lit from within by a magical source of sexual energy. Their bodies undulate with excess flesh, rather than drop straight down androgynously.

This exhibition is divided into six themes and includes works by Rubens as well as works by others whom he influenced. The last galleries are devoted to his great theme: Lust. Here are the nudes. Despite their voluminousness – their generous shape means they literally take up more space in the painting – they seem to possess little more agency than Lovelace, whose nude image circulated and titillated without her consent. What is immediately noticeable is their powerlessness.

Rubens’ nudes are preyed upon, chased, violated, drugged, tricked, cowed, surveyed, and raped. These welcoming female mounds of skin, so pearlescent they appear like sheaths of pale silk, are mostly victims. This was intentional: scenes of female violation were created in accordance with prevailing taste. They were highbrow works of pornography – however stunning – and the pleasure of the wealthy male patron depended on the female subject’s pain and denigration. Therefore, they are not too different in spirit from Lovelace’s own tragedy.

Rubens’ nudes have no sense of tragedy, however. They are not afforded such a degree of inner life. Instead, they exist to be consumed by the eyes. And, as the viewer, consume we do: their aesthetic is irresistible. This is the dilemma of desire that Rubens creates: by looking and enjoying, we are complicit.

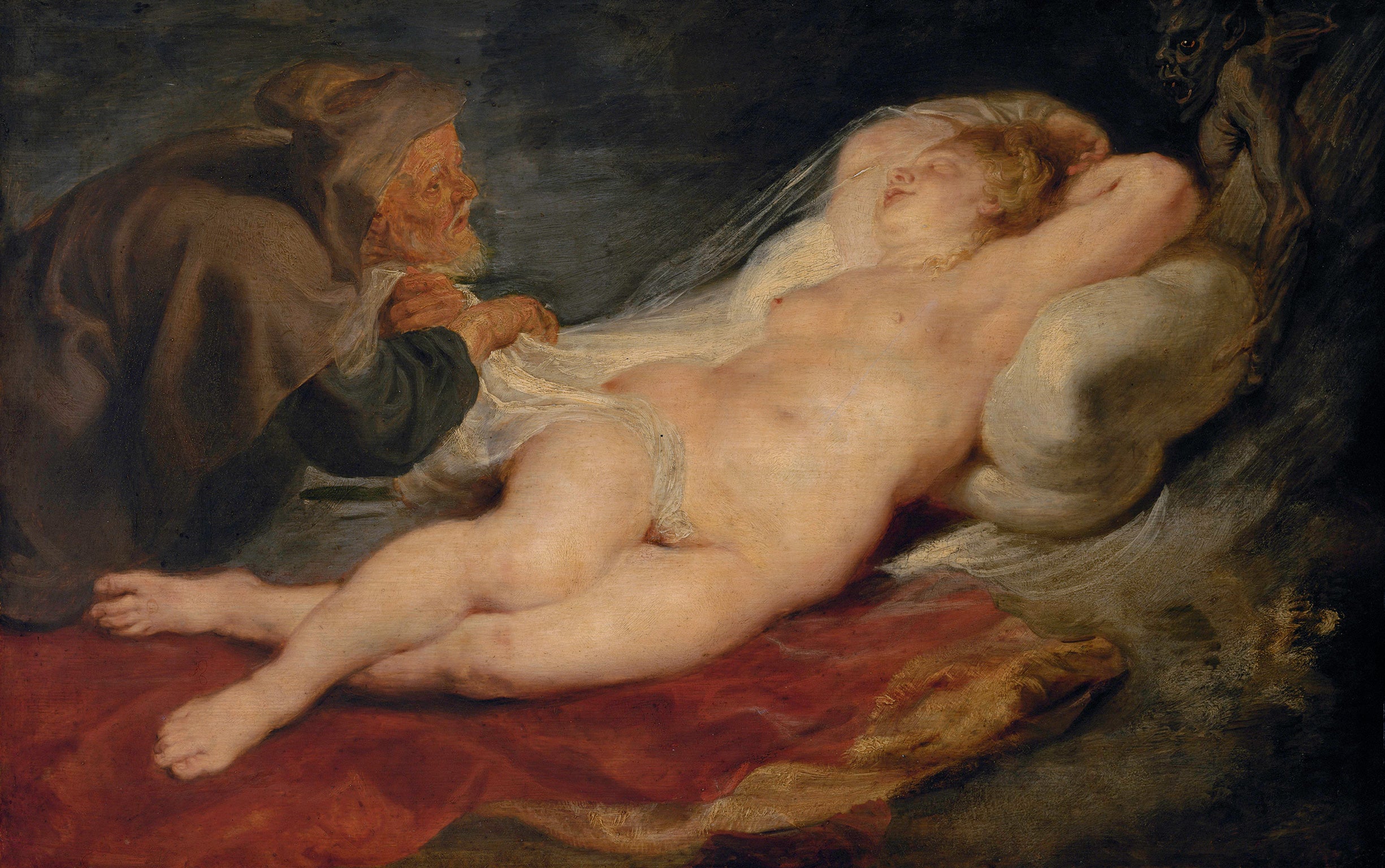

One of the most sinister of these scenes is The Hermit and the Sleeping Angelica (1626-8), which shows the lavish nude body of Angelica as she sleeps on a rich red garment. The hooded, grey-bearded old hermit desires her so much that he has already bewitched her horse in order to abduct her to a deserted island. She has resisted his advances; he has responded by giving her a magic potion, which makes her sleep – a 17th-century equivalent of Rohypnol.

The painting shows the moment when the hermit is free to watch her naked form rest at his leisure. He can touch her and look at her, but do nothing more due to his own physical deterioration. His predatory power over her lies in his gaze; the painting is sensual and profoundly creepy.

It is hung alongside a similar painting, Jupiter and Antiope (c1618) by Anthony van Dyck, who was a generation younger, worked in Rubens’ studio, and became the most prominent Flemish painter after him. The skin of Van Dyck’s nude Antiope is sharper and clearer; her creaminess is contrasted once again to the red material beneath her. She is supple, inert, prone, possibly dreaming; she has been rendered physically passive – playing dead – while Jupiter hovers above her, horns growing out his head, reaching one gnarled hand down to peel back the red cover. He is accompanied by an eagle, which holds bolts of lightning.

While the story of the hermit and Angelica comes from Ariosto’s poem Orlando Furioso (1516), the story of Jupiter and Antiope is mentioned briefly in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Despite the parallels between the works, Van Dyck’s was in fact painted about a decade earlier. This shows the continuity of themes of the era.

Peter Paul Rubens was born in 1577 and died in 1640; he was a diplomat as well as an artist, known for his sprezzatura – his style of studied carelessness. Today the word “baroque” tends to mean OTT. In 1758, the philosopher Diderot agreed. He wrote that baroque architecture was “the ridiculous taken to excess”. Baroque emerged as the dominant style across the arts during the 17th and early 18th centuries. According to the art historian Jacob Burckhardt, it spoke “in the same tongue as the Renaissance, but in a dialect that has gone wild”. It focused on appearances rather than essences, and, above all, on movement. This is evidenced in Rubens’ flamboyantly dynamic scenes in the Violence section.

In Tiger, Lion, and Leopard Hunt (1616), a man in green falls backwards off his rearing horse as a tiger mauls his shoulder. His expression is stunned. Below, two bare-chested men with rippling, opalescent muscles wrestle a lion; one holds its jaws wide open. This is man versus nature – quite different from our contemporary keenness to preserve and protect wild animals, here the latter are shown as symbolic adversary.

The colours are once again joyous, but the subject matter is absurd. It is a celebration of masculine brutishness. Some of its numerous imitators are displayed. Edwin Landseer’s The Hunting of Chevy Chase (1825-6) shows men in armour overseeing a pack of savage white dogs, fighting a stag. The scene is one of Romantic nostalgia and bloodlust. It is startling for a moment, but not particularly interesting.

The problem with this exhibition is the curation: in each section, the Rubens painting that influenced all the others should be prominently displayed. Otherwise, the show collapses into a muddled montage of paintings from different eras showing similar subject matter. Some of the original Rubens are not displayed at all, or appear obscured. Overall, the exhibition feels as though it lacks a centre.

Perhaps there was a need to compensate for lack of access to Rubens’ most famous paintings by supplementing the exhibition with other artists’ work. I would have preferred to see Rubens on his own.

Rubens was extraordinary for the drama of his work. While I understand the curatorial desire to build a crescendo, the Violence and Lust sections, which are by far the most exciting, come right at the end. First you have to get through Poetry (pastoral landscapes), Elegance (portraits of wealthy wives), Compassion (religion), and Power (the Marie de’ Medici cycle, which is not included, and instead shown on film – this is a shame). These are more muted.

However, there are some thrilling works early on. In the Compassion section, Rubens’ subtle triptych altarpiece, Christ on the Straw (1618), shows the body of Christ immediately after he is lowered from the cross and anointed prior to burial. His flesh has the Rubensesque quality of softness and light, but it is inflected with a greyish tinge, already rotting. A wound gapes from his side; blood runs over him. Mary’s eyes are rolled up and red-rimmed, as though she has been crying blood.

Rubens was born a Protestant, but converted to Catholicism. He was part of the reconquista – the aesthetic corollary to the Counter- Reformation, which sought to inspire faith and compassion through artworks. As a mode of propaganda, Catholic art became more explicit and gruesome, but the altarpiece is notable for its calm sense of sadness.

The artist Jenny Saville, known for her own morbidly obese nudes, has curated a “response” to the exhibition in an adjacent gallery – a selection of contemporary artworks that relate to Rubens’ oeuvre. It is inspired. One of the highlights is The Clairvoyant (2001) by John Currin. It is a portrait of a bare-shouldered, pale-skinned nude who appears at first to exist in the Rubens tradition. However, her large blue eyes are askew. Her slightly open mouth suggests not naivety, but wonder at a private vision. She is blind, blessed with the kind of profound inner knowledge usually afforded to the artist, not the muse.

‘Rubens and His Legacy: Van Dyck to Cézanne, Royal Academy, London W1 (020 7300 8000) to 10 April

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks