Robert Mapplethorpe's petals and penises: The relationship between the artist's floral and erotic imagery

Almost three decades since his death, a stunning new book and a major retrospective reassess the artist's legacy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

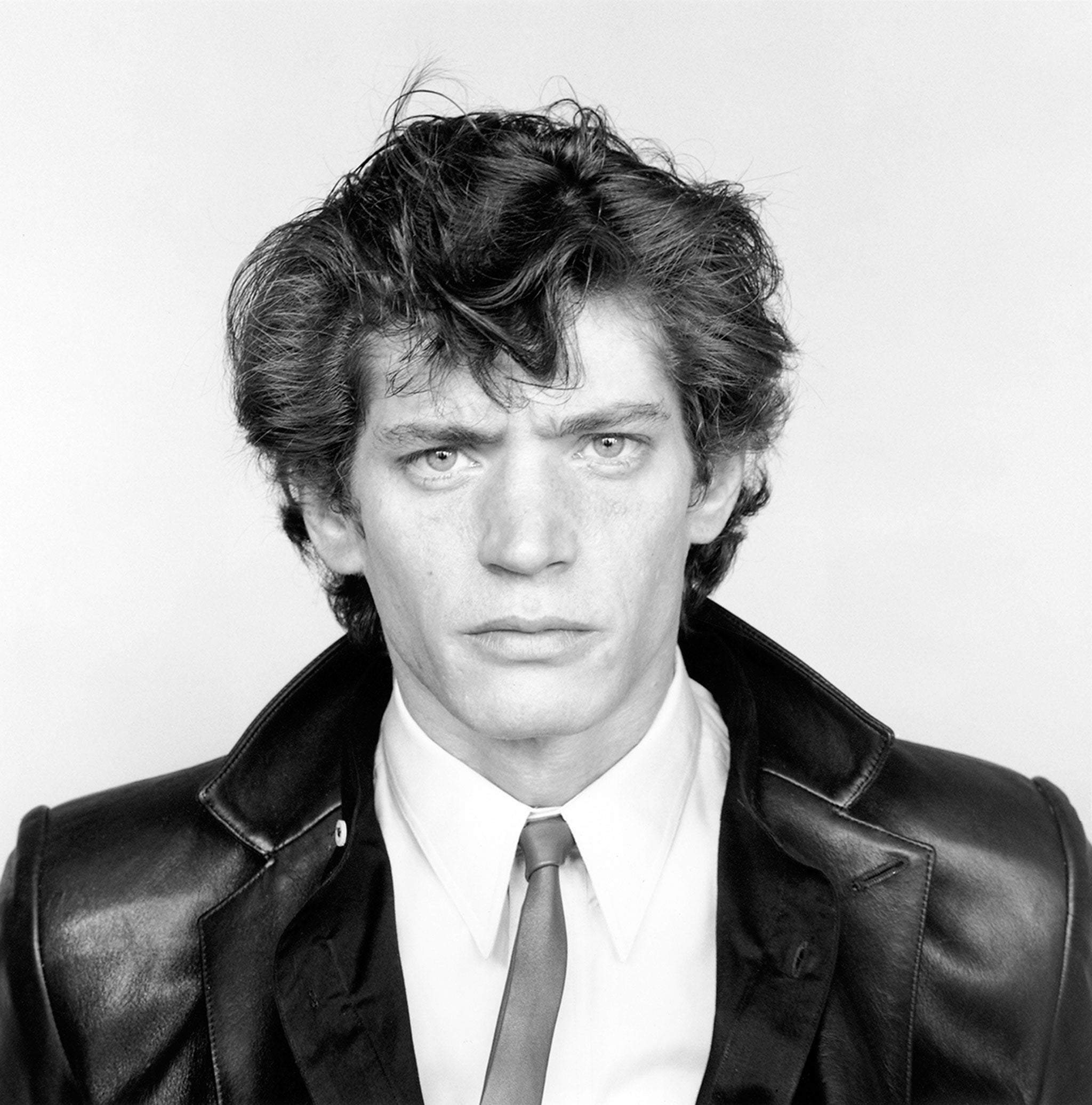

Your support makes all the difference.This week marks 27 years since the American artist Robert Mapplethorpe died of an Aids-related illness, aged just 42. He was already a star before his death, admired for his formalist black-and-white photographs of flowers, sought after for his celebrity portraits and infamous for his provocative images of male bodies bound up in S&M gear.

In the intervening decades, his reputation has only grown, nurtured by the foundation he established and bolstered by a growing number of books, exhibitions and other studies, which this year reaches a crescendo. Next week, a major retrospective of his work opens in Los Angeles at the dual locations of Lacma and the Getty Centre; next month, a new documentary is released; and a film adapted from rock star Patti Smith's memoir of her friendship with the artist, starring Doctor Who's Matt Smith, has recently been cast.

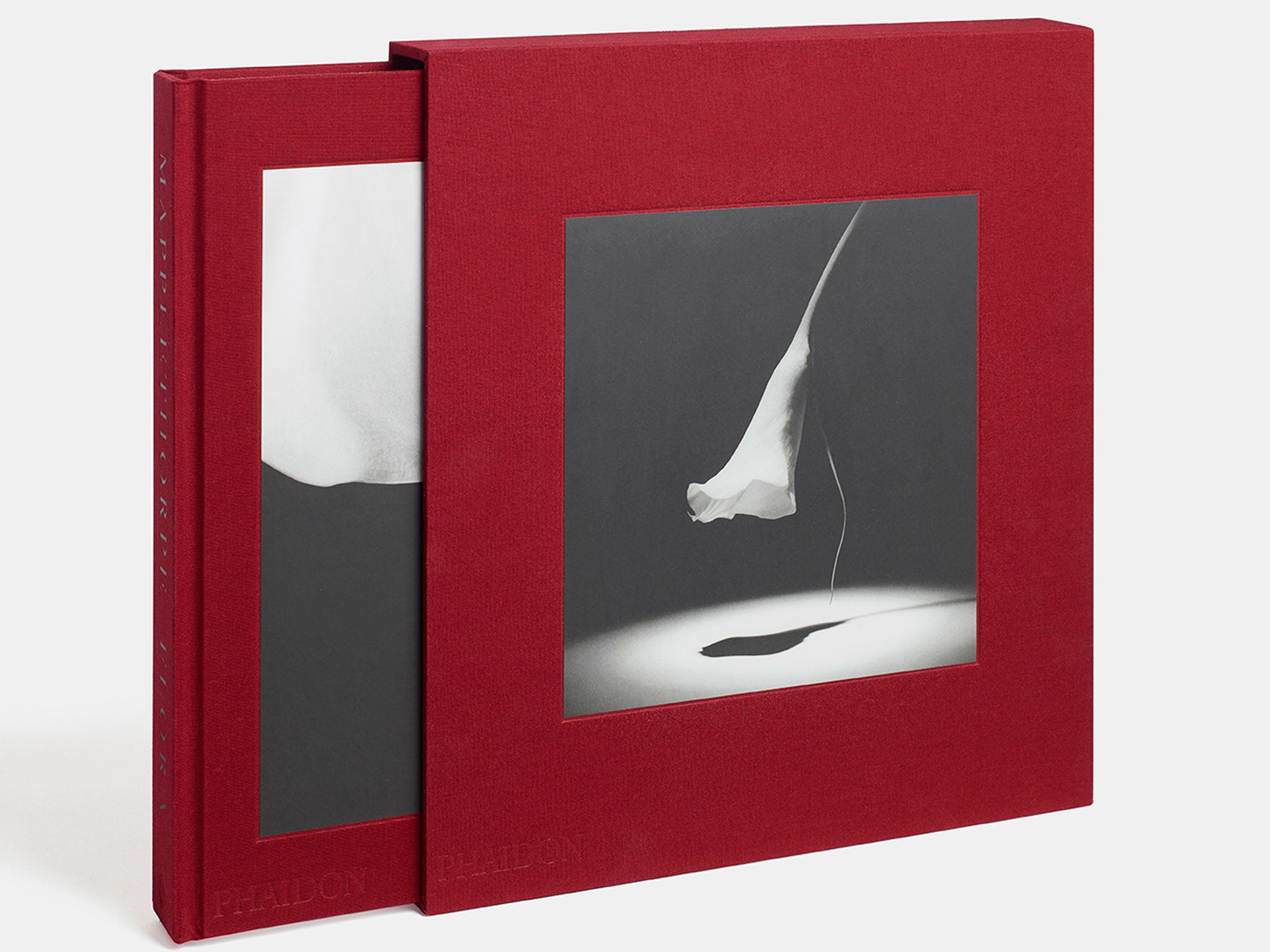

Added to this is the publication this month of a lavishly produced book recording every one of Mapplethorpe's sensuously composed studies of flowers. At 368 pages, with a blood-red slip case and a cover price of £125, Mapplethorpe Flora: The Complete Flowers is testament to the meticulous care of Dimitri Levas, who worked as the artist's assistant, and Mark Holborn, a celebrated editor of photographic books.

Mapplethorpe's earliest pictures of flowers date from 1973, not long after he had been given a Polaroid camera by his friend John McKendry, curator of prints and photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Up until this time, the artist, who grew up in Queens and studied graphic design at New York's Pratt Institute, had been making assemblages rather than taking photographs, and he used the Polaroid technology to practise composition and lighting in his new-found field.

Several of these early Polaroids appear in the new book, their sepia tones and domestic settings recalling the 19th-century photos which Mapplethorpe enjoyed collecting with his lover, the connoisseur Sam Wagstaff. Gradually his technique and equipment changed; by 1977, he had acquired a Hasselblad camera, and the luscious square-format black-and-white flower studies that became his trademark began to emerge. The settings are often minimalist, the blooms – single or in small groups – lovingly photographed with dramatic contrasts of light and shade.

Alongside these still-life studies, Mapplethorpe was taking what at first appear to be very different kinds of photographs. Many of the pictures in his notorious X & Z portfolios – sets of highly sexualised images of gay men, including "Man in a Polyester Suit", a photograph showing Mapplethorpe's black lover, Milton Moore, with his prodigious penis poking out from his flies – were also made between 1977 and 1980.

It would be easy to consider Mapplethorpe's flower pictures as distinct from these overtly erotic images, but Mark Holborn thinks this would be a mistake. "The flowers are photographed in the same manner in which he photographed sex or portraits or anything else that crossed his studio in the course of a day," he says. "He used the same camera and the same visual language – the geometry, formalism and props – so there is an equivalence between them."

In truth, there is no less an erotic element to the flowers than to any of the artist's other pictures. It's hard to look at the drooping head of a Mapplethorpe tulip without thinking of the spent male member, or at his close-up studies of an orchid's frilled fringes without visualising a vulva. Later, when he was ill, they came to symbolise other things. "The flower pictures reach a peak with the calla lilies," says Holborn. "There's a suggestion of death, of Mapplethorpe's own mortality." Shortly before he died, the artist sent his friends copies of a photograph of wilting tulips in a black vase.

Dimitri Levas first met Mapplethorpe in 1978 and describes in his introduction to the book how he became his assistant. "No one gets me good flowers, Dimitri," Mapplethorpe said to him. "I bet you could get me good flowers." Levas rose to the challenge and soon discovered the best blooms at the Saturday market on West 28th Street. "I would pick out the flowers that had the most architectonic shapes and those with the most perfect form," he writes. He would then take them back to Mapplethorpe's loft on West 23rd Street and put them in water. Later in the day, when the artist had finally risen, they would arrange the flowers together and then Mapplethorpe would photograph them as a kind of limbering-up exercise for the afternoon's portrait shots. "I remember Robert's excitement if a flower picture appeared slightly sinister," writes Levas. "He loved the way a shadow of an orchid resembled the head of a devil… Robert would often refer to these pictures as 'New York flowers'."

For all the interest and publicity Mapplethorpe still generates, the value of his work in the art market remains relatively low. Several signed and numbered prints of his flower pictures were due to be auctioned at Christie's last month in the sale of Sting and Trudie Styler's collection, with estimates ranging from £8,000 to £12,000 for a still-life of an iris, and up to £30,000 to £50,000 for a study of calla lilies (the pictures were withdrawn before the sale). His erotic images have a higher value, with a print of "Man in a Polyester Suit" selling at Sotheby's in New York last year for $478,000, the first time one of the original 15 prints of the picture had been sold for 23 years. Yet even Mapplethorpe's record price of $642,200 for a portrait of Andy Warhol still ranks some way below the top price of $2.7m paid for a photograph by his contemporary, Cindy Sherman.

But market value is not everything, and perhaps the renewed attention the artist is receiving this year will see his prices rise. In the meantime, Holborn has no doubt that Mapplethorpe's reputation will continue to grow. "He's not in the lineage of American photography; he comes from somewhere else – through the art world," he says. "People still find the sex pictures difficult, but I think they are hugely important and will be looked at for centuries." The flower pictures, Holborn adds, played a key part in the development of these works."People might look at the tulips beside them and think, 'How important are these?', but they are. If he hadn't photographed them, he wouldn't have been able to do what was to come."

'Mapplethorpe Flora: The Complete Flowers' (£125, Phaidon) is published on 14 March. 'Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures', a documentary by Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato, is in cinemas from 22 April. Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium is at the Getty Centre and Lacma in Los Angeles from 15 March to 31 July (getty.edu)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments