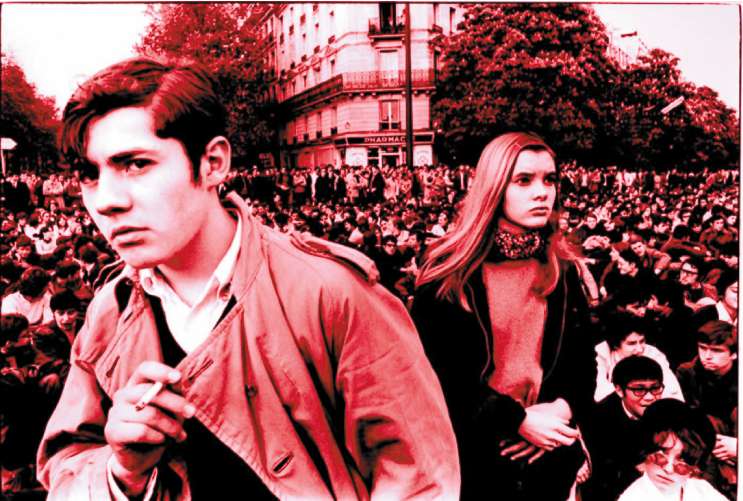

Revolution now! The 1968 Festival of Philosophy,

What was 1968 really like? At Rome's Festival of Philosophy, the cultural icons of the era shared their experiences. Peter Popham reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."Che tragedia!" exclaimed the greying lady next to me as Dany Cohn-Bendit and the other veterans of the barricades shuffled on stage. "What a tragedy! How old they've grown! I don't recognise any of them! I don't even want to look at them!"

The sacred monsters of 1968 were at Rome's Parco della Musica to debate the events of that year at its third Festival of Philosophy: the year when students from Columbia to the Sorbonne occupied their campuses, when Czechoslovakians dreamed of democracy and for a few months across the world practically anything seemed possible. "It was the year," said Cohn-Bendit, "when people realised that freedom is something you have to seize."

Along with Dany the Red were Bernardo Bertolucci, Peter Schneider, Erica Jong and numerous other ranters, writers, thinkers and makers, brought together to evoke what it felt like to be young in that dawn, and to argue about whether it mattered, and what it all means today.

Paul Berman, the author of Terror and Liberalism, who as a student at Columbia University was arrested during the year, remarked on "The weird quality of 1968, the way that, for the first time since 1848, things took place nearly simultaneously all over the world... Is there, as Hegel thought, a universal history?"

Yet if similar things happened everywhere, what they meant to the participants could be wildly different. The Red Guards were running amok in Beijing and Shanghai, and Maoism became the dominant influence on the French students in May 1968, the insurrection that defined the year more than any other event. Yet the puritanical authoritarianism of the Chinese was worlds away from the libertarianism of the European students who imagined they were inspired by the Little Red Book.

For Italy and Spain it was "the end of the Middle Ages", the year when the right of the church to impose patriarchal rules on the entire society was challenged and rejected.

Until 1968, women in Spain could not have their own passports, and adulterers and homosexuals were sent to jail. Then suddenly everything changed. It would be another seven years before Franco died and democracy could be discovered – but the reason democracy came to Spain so quickly after Franco's death, said Fernando Savater, was that "he was already a mummy in his coffin – then the door of the coffin was opened and he turned to dust."

The holistic nature of the revolution of 1968 was nowhere more apparent than in the way it transformed relations between the sexes. "Feminism emerged from 1968 the way Eve was created from one of Adam's ribs," remarked Ida Dominijanni sardonically – but in the feminist revolution, 1968 produced what she and some other speakers felt was the year's one unqualified triumph, "the only really successful revolution of the 20th century."

Adam Michnik, the Polish historian and journalist who was deeply involved both in 1968 (he spent most of the year in prison), said that affectation was the year's keynote. "The year was like a masked ball, people carried their posters of Mao and Che Guevara and Trotsky the way people at masked balls used to come dressed as lords or chimney sweeps."

Bertolucci was too old at 27 to be a classic sessantottino ("sixty-eighter"), but in a languidly magisterial conversation to a rapt hall he evoked some of the sinister magic of the year. He pointed out how the crucial cinematic influences on 1968 happened years before: "Nineteen-sixty was the year the New Wave exploded, with A Bout de Souffle by Godard, Fellini's La Dolce Vita and Antonioni's L'Avventura. I saw La Dolce Vita before it was dubbed, it was my discovery of real sound as recorded by the microphone and it was what pushed me into being a director. L'Avventura was one of the first modern Italian films; it was hypnotic."

In November 1968 Bertolucci went to London with Godard for the premier of One on One, and was witness to the row that erupted in the National Film Theatre when Godard discovered that the British producer Iain Quarrier had changed the film's ending. Godard told the audience to demand their money back and send it the defence fund of Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver; the crowd rejected the idea on a show of hands. Godard wrapped up the evening's entertainment by punching Quarrier on the jaw and storming out. It was a quintessential 1968 eruption.

But it was also a demonstration of 1968's dead ends. In that year Bertolucci made his Godard-esque film Partner, but, he said, "I found a distance growing between myself and my friends and people like Godard who were enthusiasts for China's Cultural Revolution. I found it unconvincing. Next year I made The Conformist, which was totally different in character from Partner – a film that I do not have the courage to see again."

If a cloud of gloom hung over the philosophy festival it was not only because Berlusconi had just won Italy's general election. "There were many 1968s," said the philosopher Paolo Flores d'Arcais, "but politically all have lost except the German Greens." Jong was scathing about the consequences of 1968. "The revolution of 1968 produced Reagan and Bush," she said. "A tiny minority of Americans believes in the right to life, but it has captured the White House. And the backlash against 1968 is still going on: we have an extremely conservative Supreme Court, we are giving more money to the war machine than at any time in history. For the first time in my life I feel ashamed to be an American..."

Yet if the political pendulum quickly swung back, the personal-political ratchet was another matter. Last year, Nicolas Sarkozy told a rally: "In this election, it is a question of whether the heritage of May 1968 should be perpetuated or whether it should be liquidated once and for all." Liquidation was his answer. But, as Schneider pointed out in Rome, "Without 1968, Sarkozy's marriage to Carla Bruni would have been inconceivable..."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments