Paul McCarthy, WS SC exhibition: The Naked Truth

His new set of paintings are shocking and frequently nauseating – but crucially they also have something to say about the dark heart of our society

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The word abject is defined in the OED as that which is “rejected, cast out, expelled”; it also means “despicable, wretched, self-abasing”.

Abject is a tricky word; it was given new life in 1982 when the psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva published “Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection”. She argued that the abject may be anything from “a wound with blood or pus, or the sickly, acrid smell of sweat, or decay” to a corpse that reminds us of our own mortality or “the pangs and delights of masochism.”

The abject is that which provokes horror and revulsion; it is often natural, part of us, but disgusting. We must reject it in order to conform to the rules of normal society. The abject is taboo and transgression, “beyond the scope of the possible, the tolerable, the thinkable.” Not surprisingly, artists love it.

Kristeva’s essay was hugely influential, and helped to define what came to be known as abject art. However, artists and writers were fascinated by themes of abjection long before it was named as such.

In the Sixties and Seventies, for example, the American artist Paul McCarthy was making films such as Rocky (1976), in which he wears boxing gloves and punches himself repeatedly in the face in mimicry of the Hollywood blockbuster starring Sylvester Stallone. He wipes ketchup over his penis, the fake blood of Hollywood, before collapsing on the floor. Rather than Stallone’s machismo, McCarthy’s fight with himself appears masochistic. It suggests the failure of a cartoonish kind of masculinity.

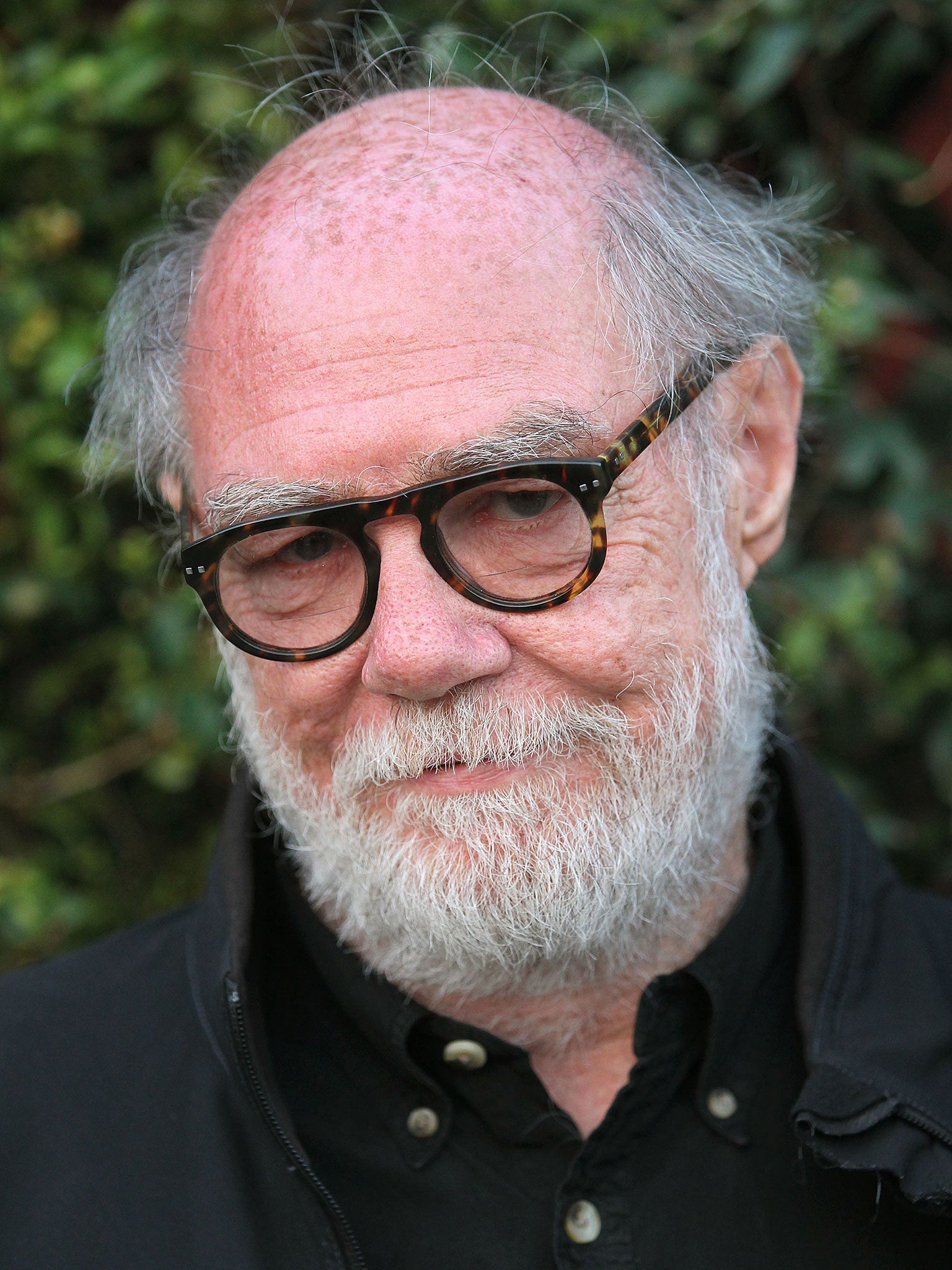

McCarthy did not sell any of his art until 1990, when he was middle-aged. Now 72, he has quickly and belatedly become a big name West Coast contemporary artist, working across film, sculpture, installation and performance. His work has always been inspired by the garish imagery of Disneyland and Hollywood. He was born in Salt Lake City in 1945, but moved to LA in 1970 and has lived there ever since. Prior to his success as an artist, he sold office furniture, installed smoke alarms, and then taught at UCLA.

The discovery of his work in the Nineties coincided with the art world’s love affair with the abject in the work of YBAs such as the Chapman Brothers, with their sculptures of limbless bodies hanging from trees. But while the work of the YBAs often seemed pointlessly nihilistic, shallow, opportunistic, McCarthy touches on something powerful and true in our culture. His work concerns violence, hyper-sexuality, and humiliation – you need only search for porn online to find a visual panoply of similar themes that would satisfy the Marquis de Sade. So much of capitalist culture seems to depend on a fetishization of inequality; he expresses it, and reflects it back in weird form.

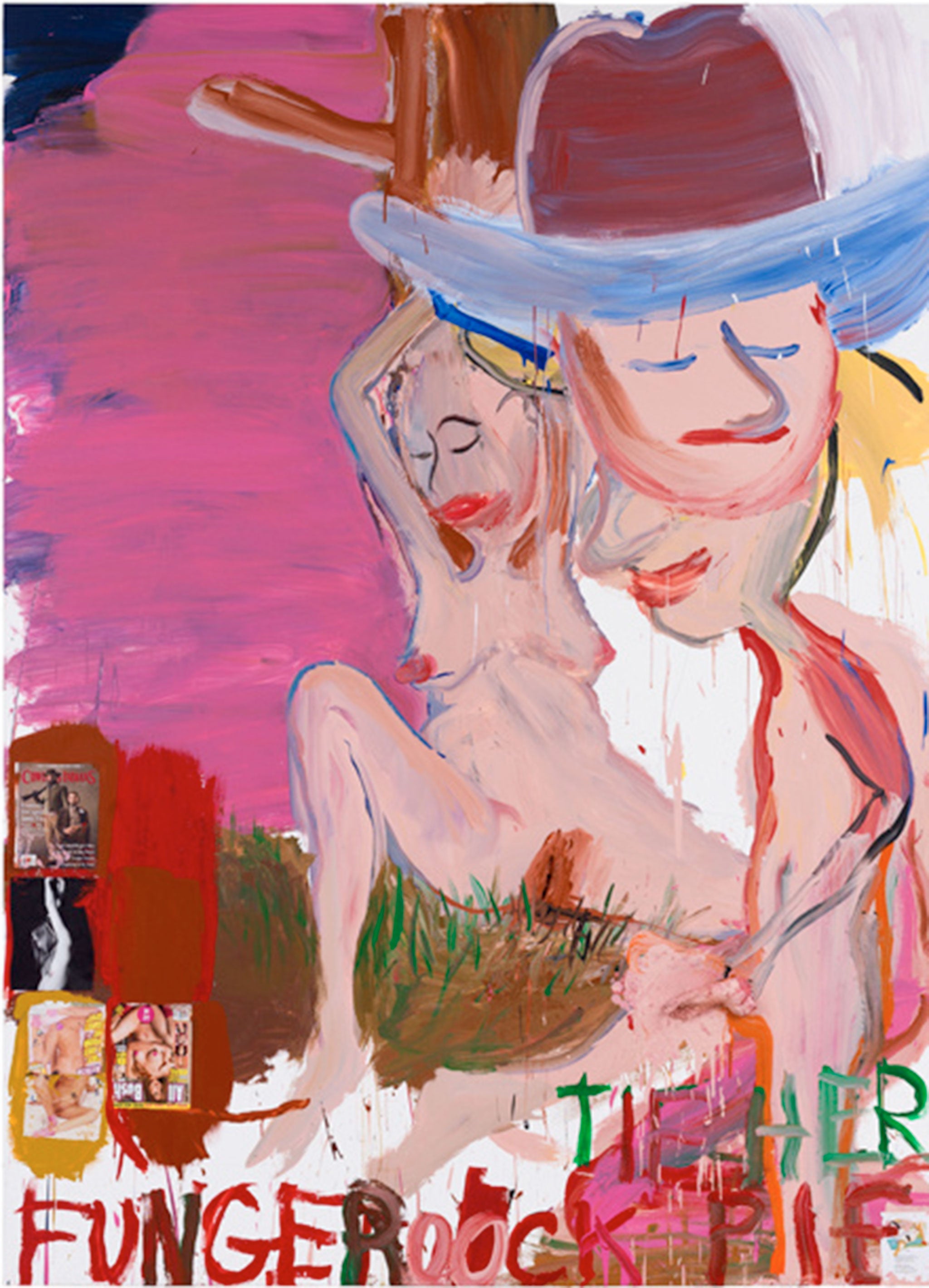

McCarthy’s first exhibition of new paintings since the Eighties has just opened at Hauser & Wirth in London. It’s called WS SC, which stands for White Snow and Stagecoach, respectively. White Snow is a reversal of Snow White, referring to both the 1937 Disney cartoon and the Grimm fairy-tale. Stagecoach is the classic 1939 Western directed by John Ford. If these films provided inspiration for the paintings, it is oblique. There is a flash of cowboy hat and Disney cuteness here and there, but most notable is the fact that the paintings show scenes of hardcore pornography.

The 16 large-scale acrylic works are obsessive and oppressive, manic and terrible, rendered in a bouncy, bright palette that evokes Californian vitality. The dominant colours are bubble-gum pink, sky blue and sunshine yellow; the weather is always wonderful in these nightmarish tableaus. Like Rocky and other early films, which are more affecting and restrained, the power of these paintings derives from their repetition. They continue to scream their obscenities at you until you can’t take it anymore. They are abject with a vengeance.

The first painting in the exhibition, SC, ECK (2014) shows a naked man and a woman hanging by ropes around their necks. Their eyes are closed; they appear mournful. Their bodies are rendered in expressive, loose brushstrokes, and supplemented by bits of collage: the woman’s hair is a real dark red curly clump of wig, which protrudes off the canvas, somehow obscene. There are other protuberances: the man’s penis is represented by a real cuddly toy with googly yellow eyes. Surrounding the couple are cut-outs from magazines: a perfume ad, and a close-up of a vagina, waxed. Here is suicide, jubilantly depicted.

While other explicit media – from films to video games to porn – may deaden you after a while, immunising you to representations of others’ suffering, these paintings have the opposite effect; they make you feel sicker and sicker, seemingly intensifying as the exhibition goes on.

One of the least explicit but most unsettling is SC, Brad Pitt (2014), in which a naked woman rides on the back of a naked man, as though he were a horse. Indeed, he appears to have four legs like a horse, as well as a mutant fifth leg that appears to be a huge penis. His face is a swirl of dirty pinks and greys; his mouth is a gash in the canvas. His head is tilted back, seemingly in sexual ecstasy. To the left, the front cover of Cowboys and Indians magazine has been pasted onto the canvas, which shows Brad Pitt looking rugged and handsome, staring into the distance, presumably a symbol of what masculinity should be.

What is unusual about McCarthy’s sadomasochistic imagination is his treatment of the female figure. Both men and women are objectified and degraded in these paintings; this is a warped kind of gender equality, whereby punishment is shared by both sexes. SC, Luncheon on the Grass (Déjeuner sur l’herbe) (2014) is named after the Manet painting, created in 1862-63, in which two women, one naked, one dressed in a flimsy white slip, picnic in a forest with two men who are fully clothed. Inequality is expressed by their varying stages of undress; the women are exposed.

In McCarthy’s reinterpretation, both the men and the women are naked. Indeed, one of the women is defecating into one of the men’s mouths. She crouches over his face and what appears to be a sock, stuck onto the canvas and painted a sour brown-yellow, emanates out of her anus. He lies below, his penis erect, his entire face discoloured by faeces. There is no trace of the forest or the picnic of Manet’s original, but instead cut-outs from porn magazines adorn the canvas, which celebrate the joys of scatology. A particularly disturbing cut-out shows a woman wearing a beanie hat with thinly plucked eyebrows: her mouth is open and filled with faeces. In the centre of the canvas, two reproductions of Manet’s painting are shown.

Unless you have a fetish for scatology, these paintings become progressively more difficult to look at. The urge to throw up gets stronger. They are disgusting and delirious, but also controlled. McCarthy’s painting is both figurative and energetically abstract, with plenty more references to the history of art.

One of the most striking paintings is the long-windedly titled WS, Statueism, Masochism Erection Statueism Frozen Pose file Spiritualism Philosophy (2014). These words are scrawled across the canvas in orange, pink and blue, alongside the figure of a naked woman standing on a plinth in a park. The painting appears tame compared to the others; the fetish emerges in her stillness. She is a human statue. McCarthy seems to be drawing a parallel between classical sculpture and contemporary pornography; in both high and low culture, the naked female body has been objectified and rendered less than human.

Despite the violence depicted in these paintings, most of the sex seems consensual. The participants will their own degradation, derive pleasure from it. In the words of Kristeva, they appear “on the edge of non-existence and hallucination.”

Paul McCarthy WS SC, Hauser and Wirth, London W1 (0207 287 2300) to 1 November

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments