On the wall: Michael Jackson's impact on contemporary art, a decade after his death

48 artists offered their responses to the King of Pop, for an exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery

“I know the creator will go, but his work survives.” Michael Jackson is quoting Michelangelo in an interview for Ebony magazine in 2007; it’s displayed at a new National Portrait Gallery exhibition named after the singer. “That is why to escape death, I attempt to bind my soul to my work.”

In August this year, the so-called “King of Pop” would have turned 60. As we also approach 10 years since his death, the gallery has launched Michael Jackson: On the Wall, an exhibition set to tour Paris, Bonn and Finland over the next two years.

Encompassing works from 48 diverse artists from different generations, backgrounds, nationalities and ethnicities in a plethora of mediums, one way to define the exhibition – as curator and gallery director Nicholas Cullinan tells me – is to say what it is not: “This is not a biography or a memorabilia collection, a retrospective of his career through the prism of music, dance, fashion or a study of his fame. This exhibition is dedicated to his influence on contemporary art.”

As such, Jackson is everywhere and nowhere in the exhibition.

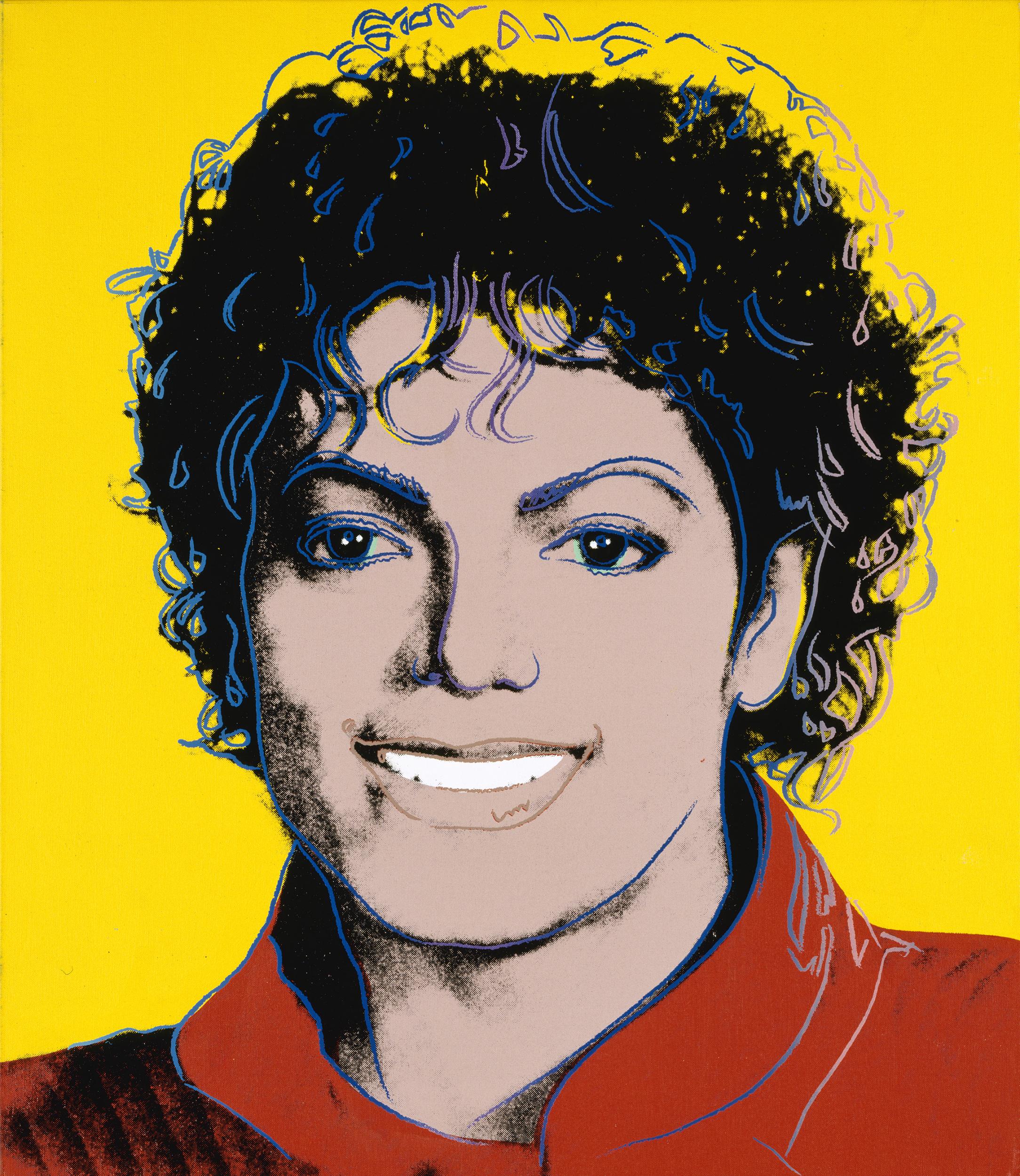

Cullinan’s idea was sparked while conducting research for an Andy Warhol exhibition nearly a decade ago. Starting from Warhol’s own screen print portraits of Jackson for Time magazine in 1984, a point of focus in one room of this show, he realised just how many artists have been drawn and continue to be drawn to Michael Jackson as a subject.

Cullinan was also fascinated by how Warhol and Jackson together were the perfect marriage of concepts in contemporary culture: the King of Pop Culture with the King of Pop.

Some of the most visually striking pieces from the diverse display are by David LaChapelle (who began his career working for Warhol). His hyper-real large-scale photographs include 1998’s An Illuminating Path, which features a still from Jackson’s “Billie Jean” short film, and a later series entitled American Jesus which use religious iconography to depict aspects of Jackson’s life which LaChappelle felt were almost biblical: his becoming both a saint and a martyr.

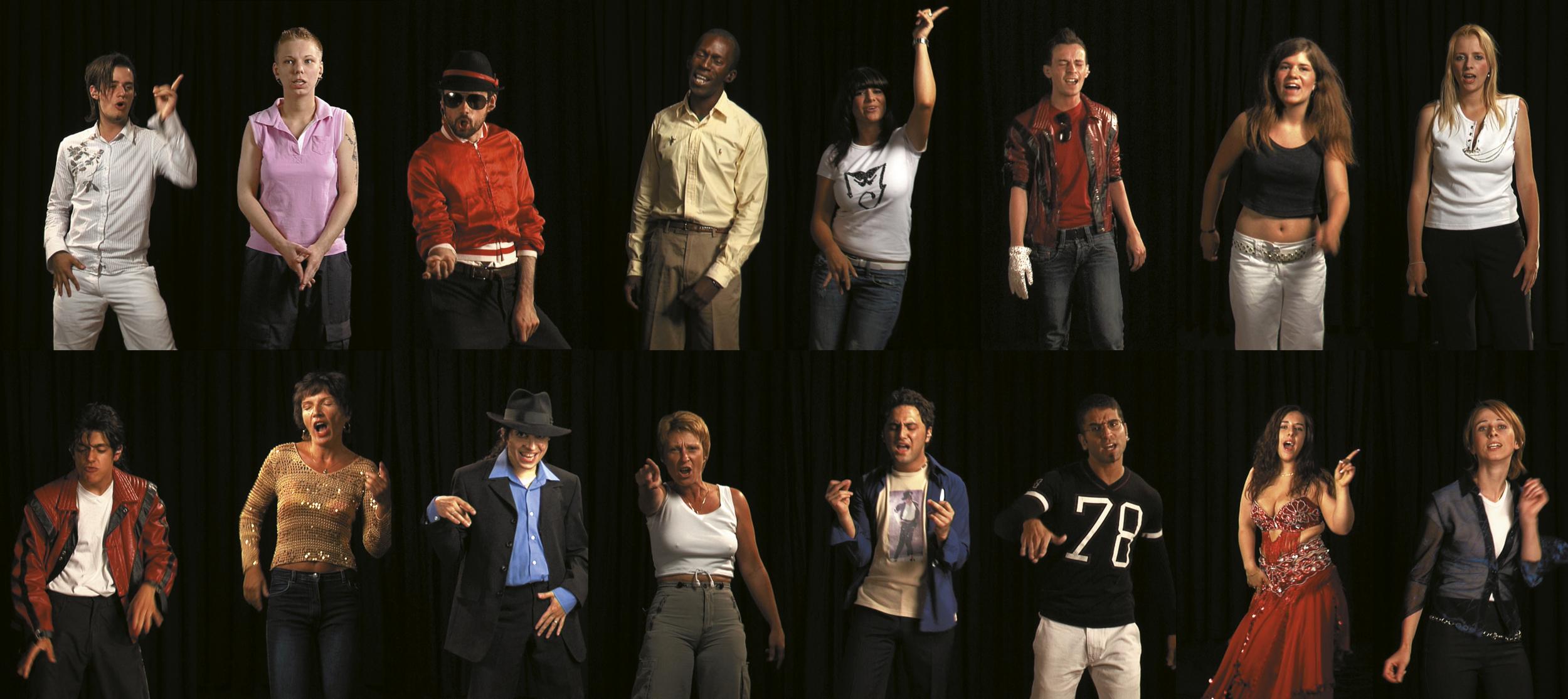

Other highlights include South African Candice Breitz’s videos of 16 German-speaking Michael Jackson fans singing all his songs since “Thriller” from start to finish, while Jordan Wolfson’s Neverland video – with an almost entirely white screen – shows only Jackson’s eye movements as he reads a statement after a high-profile court case.

A never-displayed-before portrait – commissioned by Jackson before he died but only completed posthumously – is Equestrian Portrait of King Philip II (Michael Jackson) by Kehinde Wiley, which reinterprets Ruben’s painting of the King of Spain, making comment on our expectations around race within history.

A film of Jackson’s Dangerous tour concert in Bucharest forms part of an installation, which Romanian artist Dan Mihaltianu explains came to represent the onslaught of Western propaganda which arrived after the fall of communism in the region.

A story quilt named Who’s bad? (1988) by activist and artist Faith Ringgold is displayed for the first time while priceless photos show a youthful Michael Jackson and Andy Warhol rubbing shoulders in the 1970s in New York’s infamous Studio 54. Fans will no doubt salivate over an extraordinary ‘dinner jacket’ by Michael Lee Bush, literally hung with miniature knives, spoons and forks as if tassels, that had been designed and worn by Jackson himself.

New York-based conceptual artist Lorraine O’Grady reflects on the execution of the exhibition: “There was a great potential for Michael to be diminished by the approach,” she reflects. “But I feel that instead he’s been elevated by it. Because there are so many geniuses here working with him seriously – and he still remains the greatest genius in the room.”

O’Grady wasn’t overtly influenced by Jackson growing up: born in 1934 she was not of his generation. Her point of contact came the day he died: “One billion people found themselves crying that day, half of them didn’t really know why. I was one of them. I wanted to find out why.”

In her resulting pieces, O’Grady parallels Jackson with images of Charles Baudelaire in four diptychs The First and Last of the Modernists (2010). In explaining the unlikely pairing to me she says: “The point I’m making here is there really is no difference between popular art and high art at a certain level of accomplishment and seriousness. I do feel that Michael and Charles Baudelaire are equal in genius, are equal in accomplishment.”

American painter Michael Gittes created an experimental video for his contribution, as he felt any painting simply would not capture his favourite thing about Jackson: “his movement.”

Syncing MJ dancing with Frank Sinatra’s “Fly Me to the Moon”, Gittes wanted to throw a spotlight on Jackson’s movements through recontextualising them, as well as harmoniously drawing together two masters of their art from two very different eras and backgrounds “whose work will continue to echo through time.”

Scottish artist Donald Urquhart’s A Michael Jackson Alphabet provides an alphabet’s worth of memories of Jackson’s life and career, from A for Jackson 5 song “ABC” to Z for the zombies in his “Thriller” video. For him, Jackson “was a romantic in an unromantic age. His influence on my generation was like mass hypnosis.”

In a time when the world is in “such bad shape”, Urquhart says he wants us to remember Michael Jackson and his attitude: “Life can be like a Hollywood musical if you want it to be.”

Some sections of the show delve into the more political aspects of Jackson as a figure, particularly his positioning as an African American artist brought into the mainstream. Todd Gray was the singer’s personal photographer from 1979 to 1983, documenting his skyrocketing fame from The Jackson 5 through to Off the Wall and Thriller.

Gray has a room here, where these images are transformed through collaging and juxtaposition with photos he took in Ghana. The intention is “to put Michael in the African diaspora; to start a conversation about colonialism.”

He confesses that the initial idea was a critique of Jackson, looking at him through the lens of race, class and gender. But while writing his masters thesis he had a realisation: “I am also a subject of mental colonialism, thinking my blackness makes me inferior. I was accusing [Jackson] of being inferior because of straightening his hair, straightening his nose, taking on these Western notions of beauty and suppressing the African qualities. And then I thought, ‘oh my god this is systemic, Michael Jackson is not a weird person at all.’

“It’s this American or Western culture that elevates whiteness and a certain aesthetic, and denigrates anything that’s not within that purview. That was why I made this work – so that other people can start thinking about the hegemonic power that is our media.”

British artist Graham Dolphin, who has created two new pieces that continue a series using Michael Jackson album covers, thinks that now, nearly a decade after Jackson’s death, we may finally be able to take step back and “reevaluate and reposition” him as an artist and cultural phenomenon, with some distance from the “weirdness“ that began to engulf his image towards the end of his life.

“For me, he is like Warhol in that it feels like he could be relevant for the next 50 years for different people to relook at,” he suggests.

In his new works, every lyric from each of Jackson’s songs – 160,000 words – are painstakingly handwritten written across tiles of original vinyl copies of Off the Wall and Thriller. It’s an extension of the way teenagers obsessively write or doodle on an object in order to proclaim ownership, as well as illustrating the shift between analogue paraphernalia and today’s ephemeral digital world.

Dolphin also points out how the stars we feel connected to today, such as Ed Sheeran, Adele and James Corden, feel so much more normal than artists like Jackson and Prince: “They were unique kind of alien figures that were dropped into the world and did their unique thing. I don’t think we’ll see the like ever again.”

Cullinan, however, conversely points out that what was seen as eccentricity and exoticism then can now be seen in many contemporary ideas around gender fluidity, race and identity. In this respect we can see Jackson as simply for being “ahead of his time”.

Many of the artists involved point out that, in exploring Jackson’s impact on contemporary art, the exhibition in fact throws up many wider themes acutely relevant to today, as discussions around race, identity, gender, fame, and image versus reality only seem to be intensifying. As a study of how audiences and artists reacted to Jackson and his art then and now, the show reveals just as much about us as it does about the “Man in the Mirror”.

A 1985 quote from James Baldwin included in the exhibition sums it up: “The Michael Jackson cacophony is fascinating in that it is not about Jackson at all. He will not swiftly be forgiven for having turned so many tables. Freaks are called freaks and are treated as they are treated – in the main, abominably – because they are human beings who cause to echo, deep within us, our most profound terrors and desires.”

‘Michael Jackson: On the Wall’ is at the National Portrait Gallery until 21 October (npg.org.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks