Mat Collishaw's new show 'In Camera': Death, sieges and crushed bugs

Mat Collishaw was once called 'the nastiest of the Young British Artists.' He shows his latest installation to Alice Jones

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It's Monday afternoon and Mat Collishaw emerges from the King William in Camberwell, blinking and with a cigarette in his fist. It might be the perfect vignette of former YBA behaving badly were it not for the fact that the cigarette is electronic and the handsome 1930s pub, still advertising LONDON STOUT in stone carving above the door, is Collishaw's studio and home.

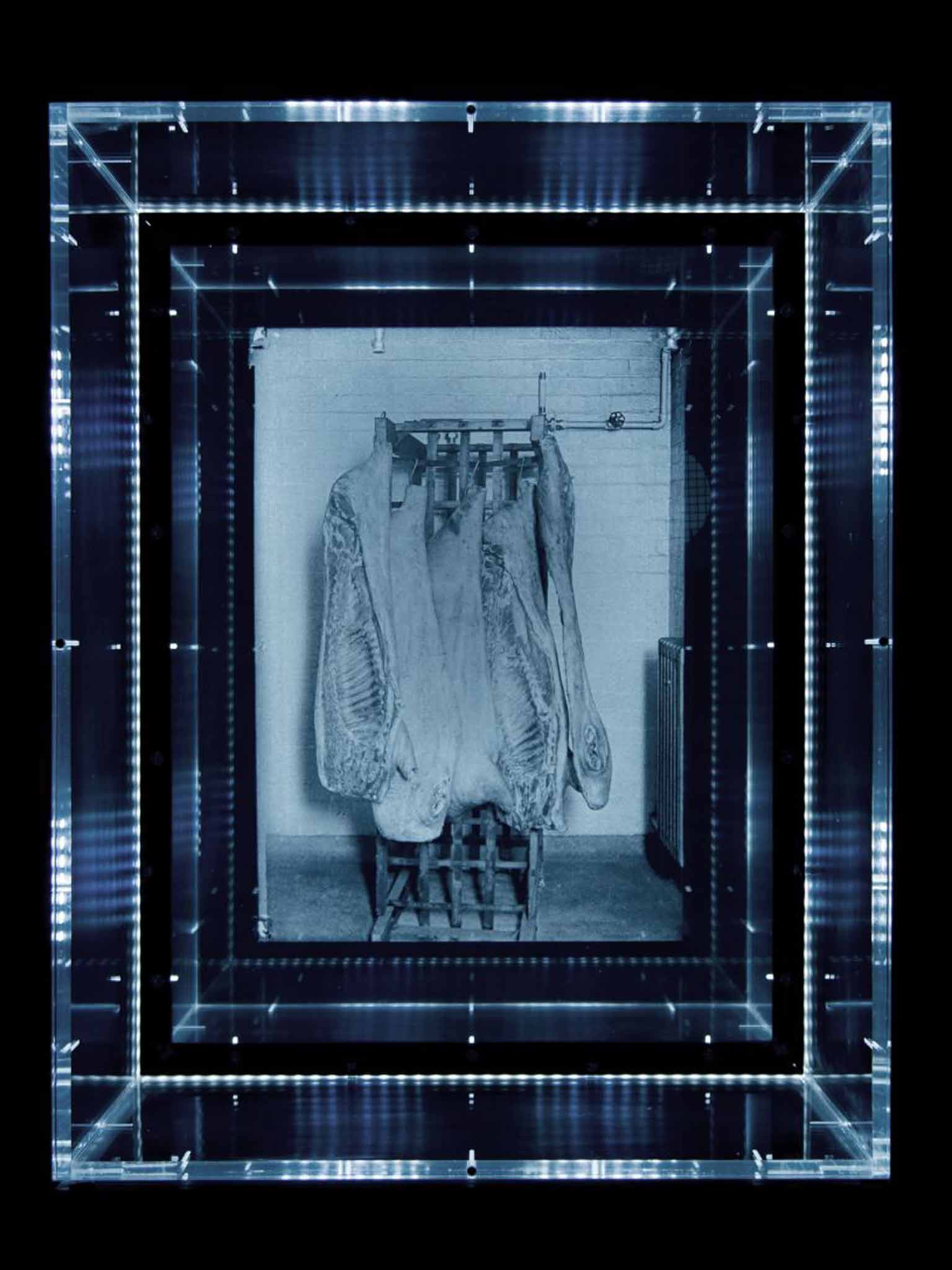

He ushers me inside – and into pitch darkness. The windows have been boarded up, and only odd flashes of white light pierce the black. "Shall we talk about this first?" he says gesturing into the gloom. OK. "This one is five sides of bacon," he says, pointing to a picture in a glass box. "And this one is a murder scene – child victim, injuries to the head or something…"

The grisly ensemble is Collishaw's latest installation, In Camera. Invited to create a work based on the Library of Birmingham's photographic archive, Collishaw dug up a box of uncatalogued crime scene negatives made for Birmingham City Police during the 1930s and 40s. "There were a lot of pictures of old men in top hats at the zoo – all very nice but there was nothing I could do with them," he explains. Instead, there will be a darkroom filled with 12 large negatives, printed in phosphorescent ink, that are lit up in turn as if by the flashbulbs of scenes-of-crime officers. "This one is an abortion," he continues in his low growl. "And that's an interesting one. It's a dentist's chair and… Well you can guess what went on there. Bit of chloroform… sexual abuse, basically."

It is a return of sorts to where it all began for Collishaw, now 48. His close-up, backlit freeze-frame of a head wound, Bullet Hole, taken from The Color Atlas of Forensic Pathology, gave the notorious 1988 exhibition "Freeze" its name – and gave Collishaw his big break, alongside Goldsmiths contemporaries Damien Hirst, Sarah Lucas and Michael Landy.

We go upstairs, into Collishaw's home. He moved in five years ago, taking over from a company who used the building for television shoots. "So nobody can argue that I'm closing pubs in the area." He stripped everything out when he bought it. "The AGA is the only thing left," he says, putting the kettle on. Upstairs are four bedrooms and a roof terrace for barbecues. A neat office leads out onto a terrace, dotted with Collishaw's diseased flower sculptures. In the kitchen a blackboard has the word "Alpen" scrawled on it but things get less domestic in the living room with its wall of antlers, funereal vase of lilies, large print of a crushed bug (one of his Insecticide series) and a bat in a glass box.

The latter is an antique, but it brings to mind Collishaw's partner, Polly Morgan, the artist/taxidermist, whose stuffed animals are collected by the rich and fashionable (he dated Tracey Emin for five years previously). They live here with Collishaw's grown-up son, Alex, and Morgan's dogs, Tony and Trotsky. Is he not tempted to leave the urban rush behind, like his old pals Sarah Lucas (now in Suffolk) and Damien Hirst (Devon)? "My girlfriend would like to but then it just means you've got to drive in every time you want to go out and party."

We sit down in front of a model of The New Art Gallery in Walsall, where Collishaw is about to open his largest UK solo show to date, and his first in a public gallery for 10 years. What took him so long? "I get bored very easily," he says. "If you want to be a successful artist, it kind of pays to have a readily identifiable brand…" Like spot paintings or neons, say. "It's possibly more difficult to get a handle on what I do because I'm moving around so much. But I think there's a core and by bringing it together, people might be able to see those threads and not see me as a loose cannon or flibbertigibbet."

How would he describe that core? "Kind of dark and what did you call it? Morbid." (I did). "For me it's not an unhealthy obsession but I do have an interest in the unhealthiness of society." So there will be his photographs of the last meals of death-row prisoners, sick flowers – sculptures of exotic species embellished with syphilis pustules, which he made by hand – and blown-up scans of crushed insects. He doesn't squash them himself. "I pretend but I send off for them on the internet and they arrive in a little envelope from Korea or wherever."

One can only imagine what his postman must think, what with Morgan's trade in stuffed chicks. Do the couple spend a lot of time talking about death? "I think she slightly resents making work in an area that can be seen as being morbid or dark and she's trying to extract herself from it. So basically I don't think she wants me to be mentioned in the same sentence as her," he says darkly.

The pièce de résistance of the show is a new zoetrope based on the Massacre of the Innocents, a migraine-inducing carousel of depravity with 300 3D figures, flashing lights and a motor. "Before you know it, you're complicit in it, you're watching it and enjoying it."

Collishaw was brought up in Nottingham as a Christadelphian, a Christian sect that forbids women to work and bans television. Do his parents like his work? "Yeah... When I made Bullet Hole I told them I'd made a picture of a flower. Then I brought them to the gallery and said, 'Look it's not quite a flower… It's more a skull with a wound in it.' They said, 'Oh that's nice.' They've always been very kind to me."

Does he tire, as he nears 50, of being called a "former YBA"? "It is a little tedious, but it's been going on for so long you become impervious to it." Is the gang competitive? "Yes, which is a very good thing. If somebody makes very good work, it makes you want to make better work." Does he wish he'd made as much money as some of his contemporaries? "I think it has become more apparent what some people's motivations are as time has gone by. Some crave more of a public profile, some don't."

He is already planning his show at Hirst's new Newport Street Gallery in London. "It's very strange but he's done stranger things. He ceases to shock, really, because everything he does is so spectacularly outrageous."

Speaking of outrageous, is he still the "nastiest of the YBAs" as he was once called, or has he mellowed? "Nasty? I hope so. Unfortunately, human beings are very prurient creatures so I like to make work that is about that prurience. If I then run the risk of being nasty that's just something I'll have to live with. Sometimes you need something to be a little bit abrasive to get people to engage. To see the festering hell beneath."

Mat Collishaw, the New Art Gallery, Walsall, 25 September to 10 January 2016; In Camera, Library of Birmingham, to 10 January 2016

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments