Mark Wallinger: Turner Prize-winning artist's new exhibition shows he still has a sense of humour and mischief

The enormous 'id paintings', which are 360cm by 180cm, demonstrate that with this artist size always matters

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Good to see that Mark Wallinger has not entirely lost his sense of fun. In Ever Since, one of the video installations that make up half of his new solo show ID, a truncated barber’s pole rotates mysteriously over the otherwise motionless, life-size shop-front of Pall Mall Barbers. Although Wallinger doesn’t inform us, this piece shows the branch of the gents’ grooming emporium beside the National Gallery. On its Victorian façade, you can just about read the come-on line for shave-and-trim nostalgists: “Traditional Service in a Modern Manner”.

Just so. The Essex lad, a bit too old, smart and versatile for YBA status, has long known how to brush up retro imagery and time-encrusted rituals so that they tell another story. After all, he has bought a real racehorse as an artwork, taken a Union flag customised with his own name to an England international at Wembley, and won the Turner Prize with the reconstruction of lone eccentric’s anti-war protest. The other portion of his first exhibition at Hauser & Wirth in Savile Row does take Wallinger in a fresh direction. More later about the massive “id paintings” in the North Gallery. But the film, video and sculptural works in the South Gallery hint that he has not quite reached the end of the well-trodden path that leads from satire to metaphysics, politics to psychology.

For the most part, time and its passing haunt the camera-based works in ID. In Shadow Walker, the artist – or rather, his sandal-shod lower limbs – strolls through Soho. On this sunny day, an elongated shadow precedes the solitary walker over the London pavement’s gunge and grime. Perhaps this highly literary creator thought not only (as he writes) of Baudelaire’s flâneur through the city, but T S Eliot’s “The Waste Land”: “I will show you something different from either/ Your shadow at morning striding behind you/ Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you;/ I will show you fear in a handful of dust.”

The disquieting experience of time also spins around Orrery. Here, four screens depict a circuit by car around a roundabout besides an oak at Fairlop in Essex, close to Wallinger’s birthplace. Each screen shows the tree in a different season, while – like the sun in an “orrery”, or articulated mechanical model of the solar system – the viewer stands in the centre. We become (Eliot again, this time from “Burnt Norton”) “the still point of the turning world”.

Yet a sense of mischief rooted in pop-culture allusions has not quite deserted him. Take Superego. It recreates the revolving cheese-wedge of the New Scotland Yard sign, which turns ominously behind every TV report of mayhem, murder or police malpractice in London. Wallinger’s pole-mounted prism replaces the Met’s iconic lettering with mirrors. Dutifully, the artist cites chunks of Michel Foucault to explain the guilt-inducing power of the ultimate police badge that represents “the seat of authority, the all-seeing eye”. Yes, good old Mick Foucault: that obligatory theoretical prop of Eighties art-school degree-shows. The philosopher must count as a cult vintage brand himself these days.

Those mirrors also reflect Freud, and indicate the self-punishing function of the social superego. In a country crowded in world-record numbers with often-inoperative CCTV cameras, the unseen powers-that-be induce us to monitor, convict and perhaps condemn ourselves. So far, so 22-carat Goldsmith’s College: where Wallinger studied and taught in the 1980s. But recall as well the Yard sign’s role as a symbol of inexorable justice in public-service cop shows such as Police 5, presented by the lugubrious Shaw Taylor throughout Wallinger’s Essex childhood. He was born in Chigwell in 1959, and grew up in a left-leaning and arts-loving family: his fishmonger father took the kids to the ballet. “Keep ’em peeled”, Taylor would sagely advise viewers as he signed off another bulletin of burglaries, frauds and GBH. One finger in English popular culture, another in Parisian theory, a third in post-Duchamp modernist art practice, Wallinger has always supped on a variety of pies.

The pay-off from this eclecticism came in a capacity for resourceful self-invention. A life-long fan of the turf, in 1994 the high-concept prankster bought, and ran, a racehorse called A Real Work of Art. By 1999, he had morphed into the lightning-rod for postmodern spirituality who filled the fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square with the enigmatic sculpture Ecce Homo. Then, in 2006, admirers found a cultural focus for post-Iraq dissent when he rebuilt Brian Haw’s marathon sit-in for peace outside Parliament. As State Britain, it won the Turner. His major projects, though, did have a continuity and coherence: above all, in the quizzical interrogation of institutions that borrowed the heraldry and pageantry of sport, of nation or of faith, then turned them inside out or upside down. The mirror-faceted Scotland Yard sign belongs in this vein.

As with many British creators of the Eighties and Nineties, a delphic ambiguity marks the tone of many works. You couldn’t simply label these sardonic explorers of the way we live now as satirists and social critics, although satire and critique did lend them fuel. Rather, they held a slyly polished mirror up to the times. Think of Wallinger, at least until recently, in the company of a photographer such as Martin Parr, a film-maker such as Patrick Keiller, or a writer such as Iain Sinclair. You might call this team the Higher Deadpan squad. Perplexed more than furious about the state of their nation, they inspected the entrails of its culture – its customs, habits, iconography – for symptoms but left a final diagnosis to the audience. Remember those post-cinema arguments about the films of Mike Leigh: is he having a laugh, and at whose expense? Bigging us up, or putting us down? With the British school of Higher Deadpan, beauty – or banality – often rested in the eye of the beholder.

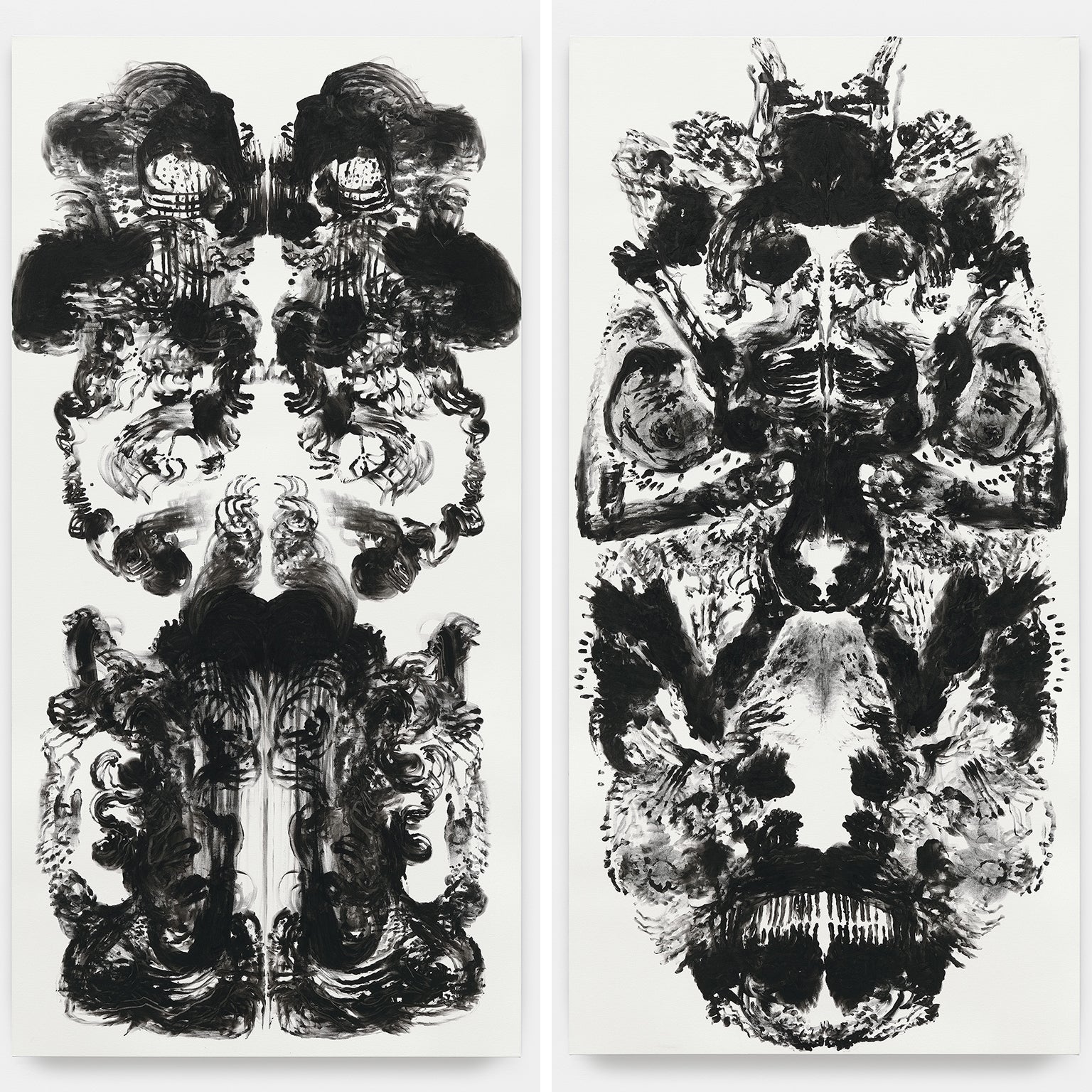

So it feels apt that the idea of the Rorschach Blot should spring to mind when you enter the North Gallery and encounter the vast monochrome acrylics of Wallinger’s “id paintings”. Here, the self is no longer the anxious slave of time and power evoked in the video works but a free agent able to make and paint, though still prey to unconscious drives. Before we reach these paintings, Wallinger juxtaposes two prints of iPhone photos of his hands. They make up a homage to, or parody of, God’s fingertip gift of life to Adam on Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling. He calls this work Ego. Then we meet the Id.

The paintings are enormous: 360cm by 180cm, or twice the artist’s height by his span across. Their bilateral symmetry echoes, so Wallinger says, the Vitruvian Man of Leonardo: that familiar trademark of post-Renaissance creativity. Here, though, these matching labyrinths may remind you more of the human brain, with its parallel hemispheres. Seemingly form-less and figure-free, these abstract explosions of black on white aim to drive deep beneath the ego into Freud’s mutinous id, “primitive, illogical, irrational and fantasy-oriented”.

To be human, though, is to seek order in chaos. Hence the Rorschach allusion. Of course, every visitor will look for shapes, for stories, here. As Wallinger writes, “Recognition of figures is a reflection of our own desires and predilections, a mapping of the territory. We invite your introspection.”

Not only the works encourage us to spin a yarn. The setting does too. I imagined not just the slides and sections in a neuroscientist’s lab but the great hall in the palace of some toppled dynasty, as its outsize Gobelins or Aubusson tapestries fade into near-indecipherable memories of heroes, gods and myths. Do you see that double-headed imperial eagle? Or the thunderclouds from which a deity flings bolts? Surely, you can’t miss that Gothic dance of death with its cavorting skeletons? Not to mention the giant pudenda that engulfs us…

And so on. Rorschach-style, every viewer can trace a tale to suit them here. That includes the artist. Treat these works as some sort of deeply coded self-portrait, encrypted in a language beyond the reach of shrinks. Wallinger relates his “instinctive” and “intuitive” method in these paintings to prehistoric mark-making in a cave: a primal release of energy. He has dispensed, he claims, with “the paint-loaded brush of expressionism”. Perhaps. However, some art-loving spectators will find it hard to forget the large-scale sequences into which post-war non-figurative painters have poured a form of spiritual autobiography. Think, for example, of Mark Rothko’s chapel in Houston.

Stripped down to monochromes, Wallinger’s id paintings may betray a self diminished by the technology of control and surveillance evoked in the show’s other works. Still, with this artist, size always matters. Remember that one of his most discussed artworks does not yet exist: the gigantic white horse, 50 metres high, that will – if it comes to pass – greet travellers at Ebbsfleet in Kent. The state may shrink us. Time imprisons us. We can still dream epic dreams.

Mark Wallinger’s ‘ID’ continues at Hauser & Wirth, 23 Savile Row, London W1 until 7 May (hauserwirth.info)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments