The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Light Years: the exhibition proving photography is an art form in its own right

Sue Davies pioneered London’s first-ever artistic space for camera snapshots when no one else would. Now, Alex Marshall delves into its 50-year anniversary exhibition at the Photographers’ Gallery

In 1968, Sue Davies was working as a secretary at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London when a colleague got sick, and she found herself left to finish off a photography show they had been working on.

The exhibition, held the following year and focused on images of women, was a hit. Visitors lined up down the block to get in, and Davies asked the institute’s founders if they would consider showing more photography. The response, she said, was not what she had wanted: they had only commissioned the last show, they told her, because they were offered the pictures for free.

That made Davies lose her temper, she later told The British Journal of Photography. So she made a decision: if museums didn’t want photography in their spaces, she would start her own.

Three years later, in January 1971, Davies opened the Photographers' Gallery in a former tearoom in the West End of London. It was the city’s first exhibition space dedicated to photography; its aim, Davies wrote in her original proposal, was “to gain recognition for photography as an art form in its own right”.

Fifty years later, the Photographers’ Gallery has succeeded — it is now housed in a grander, five-story building and is celebrating its half-century with a series of exhibitions, called Light Years: the Photographers’ Gallery at 50, through 1 February 2022.

David Brittain, a former editor of Creative Camera magazine who curated the anniversary shows, says the gallery “put up the scaffolding” for photography to be considered seriously in Britain.

Martin Parr, a photographer known for his humorous images of British life, echoes the sentiment. “Here was somewhere you could feel part of a community,” he says of the gallery. “It became a place of pilgrimage, almost.”

Oliver Chanarin, a winner in 2013 of the gallery’s annual Deutsche Börse prize, says that the greatest success of the Photographers’ Gallery “was, in a way, to make itself redundant,” noting that it had paved the way for many other dedicated exhibition spaces and museum shows to open around Britain. (Another pioneer, Impressions, opened in York in 1972.)

Here was somewhere you could feel part of a community

Davies, who died in 2020, is widely praised for her pioneering role, but the project could easily have ended in disaster. “Sue had to remortgage her home and went without a salary for 18 months,” Brett Rogers, the gallery’s director since 2005, says in a telephone interview. (In 1973, Davies told The New York Times, “We suffer from a chronic lack of money”.)

But the exhibitions she organised soon found an audience willing to pay a small entry fee.

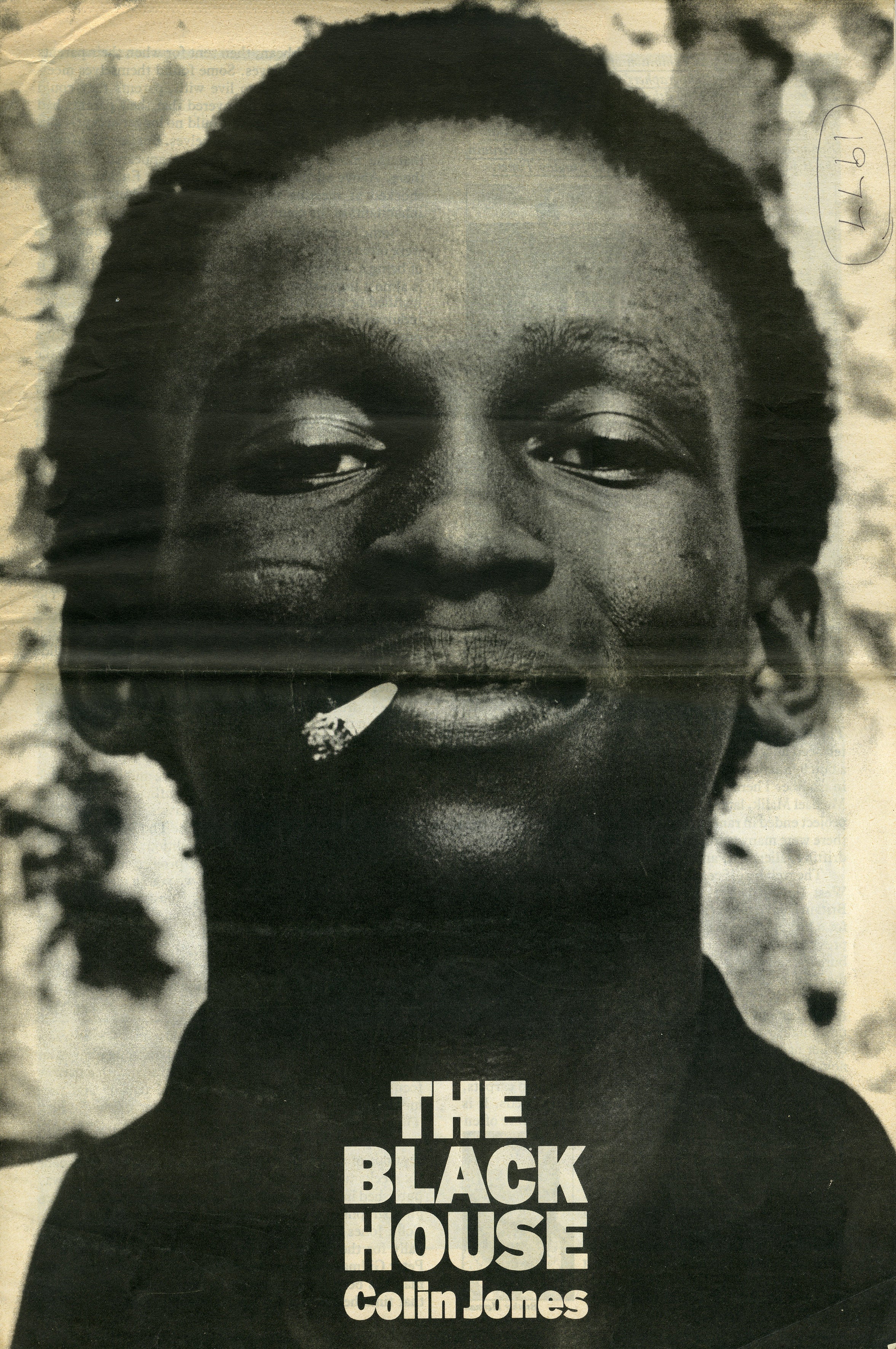

The gallery’s initial focus was on reportage, displaying socially conscious photographs shot for newspapers and magazines. Among those were the striking images of the residents of “the Black House,” a London hostel for young black people, taken by Colin Jones and featured in a 1977 show.

Yet soon Davies was branching out, hosting a retrospective of work by fashion photographer David Bailey, and another of images by Floris M Neususs, a German photographer who made lifesize portraits of his subjects.

In the 1980s, the gallery showed work by black photographers, including the group D-Max, as well as more photography by women. In the Nineties and beyond, thematic exhibitions explored issues such as photography’s role in the age of computers and its use in surveillance. There have also been shows featuring star artists such as Catherine Opie, Taryn Simon and Wim Wenders.

The gallery’s variety sometimes proved too much for traditionalists. In 1978, it held a show, called “Fragments,” of photo collages by John Stezaker. The artist recalled in a recent telephone interview that his cut-and-paste approach had gone down badly. “I can remember the chairman of the patrons writing a several-page diatribe against me in the visitor’s book, hinting very strongly that Sue would lose her funding if she kept promoting this rubbish,” he says.

Stezaker didn’t exhibit at the Photographers’ Gallery again until 2012, when he won the Deutsche Börse prize. “Sue felt as vindicated as I did,” Stezaker says.

In the 1980s, the gallery received complaints of a different kind for its show of photographs from The Face, a youth culture magazine. According to Brittain, some photographers felt that the images glorified consumerism, undermining photography’s true mission: to expose social ills. “It showed the fault lines emerging between generations,” he says.

Occasionally, the controversies were more serious in nature. In 2010, the gallery held an exhibition by Sally Mann, an American photographer who shoots portraits of her children, naked, and who has been accused of producing child pornography. After hearing about the show, London police investigated but decided that the images were not obscene. “We defend it as art, and we always will,” Rogers says.

Two years later, the Photographers’ Gallery moved out of its original premises, near Leicester Square. With two exhibition spaces on either side of a West End theatre, accessible to each other only via the street, the original setup was awkward, Rogers says. When it rained, visitors got stuck, she noted, and only one of the spaces had restrooms.

The gallery’s current home, in a redeveloped warehouse near Oxford Street, will next year become the anchor for a local council initiative called the Soho Photography Quarter, intended to rebrand and develop the surrounding area.

So what role is there for the gallery today, when photography is so accepted and admired that part of London will be renamed after the art form?

Chanarin says that the gallery was “needed more than ever”. Photography had “become a more complex and layered medium” thanks to smartphones and social media, he notes. Photographs now watch us and the choices we make, as much as we look at them, he added, pointing out that apps like Instagram log every image a user likes. Spaces like the Photographers' Gallery are needed to explain the changing context of photography, he says.

Rogers agrees that the gallery’s role is vital in a time when “everybody thinks they’re a photographer”. The challenge for the institution, she adds, is to say, “Well, yes, but what makes a memorable photograph of the kind that lasts centuries?”

Despite all the changes, this sounds a lot like Davies’s mission when she started the gallery 50 years ago: to bring exciting photography to the public and to make them want to come back for more.

Light Years: The Photographers’ Gallery at 50 runs at The Photographers’ Gallery until February 2022. tpg.org.uk

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks