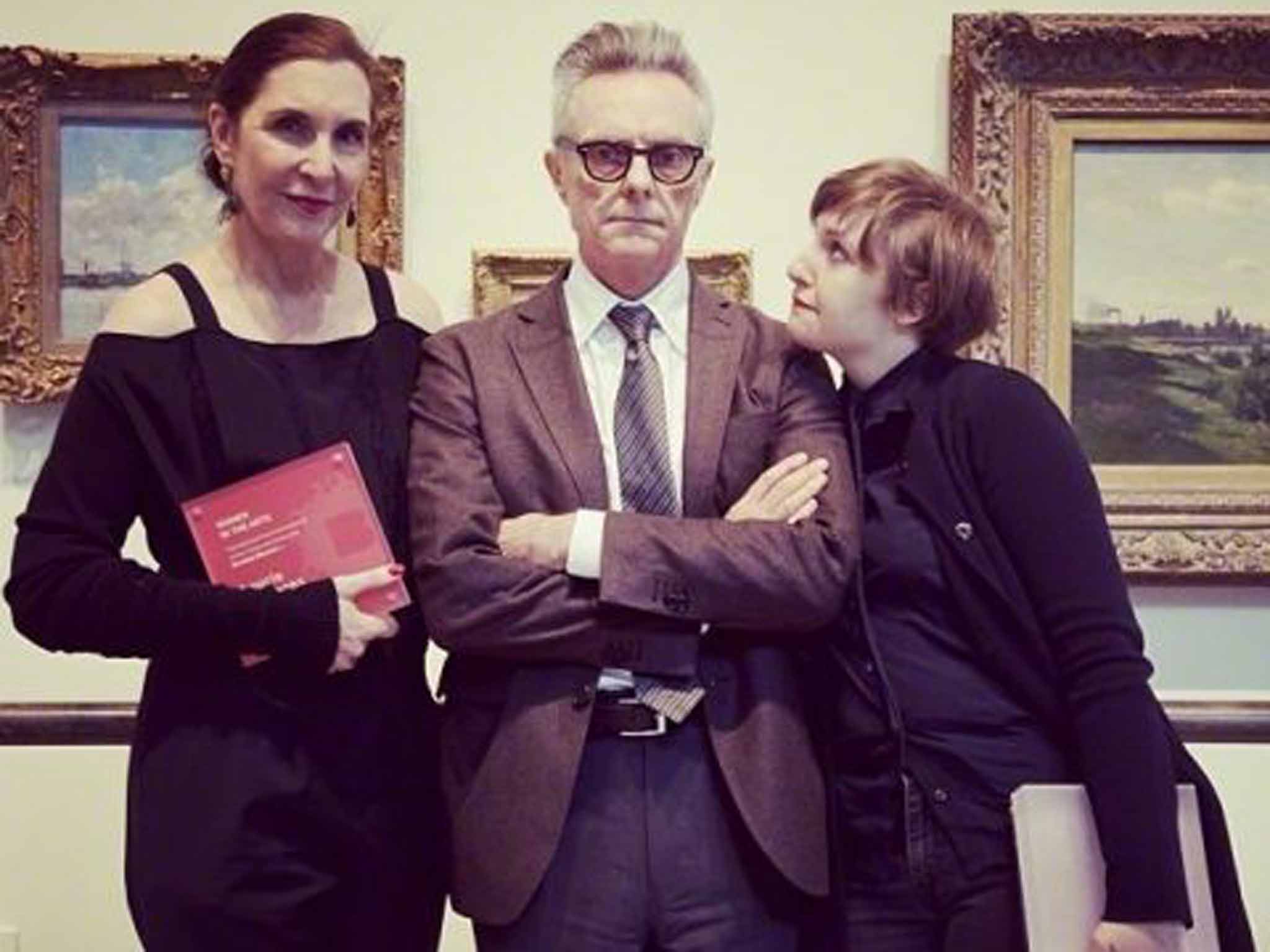

Lena Dunham and her family of artists

How many artists – and egos – can one home accommodate? Sarah Thornton, author of the new '33 Artists in 3 Acts', steps into the lives of celebrated artists Laurie Simmons and Carroll Dunham and their daughters Grace and Lena (with whose work you may be familiar...)

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What is an artist? And who do artists think they are? That was the question I set out to answer in my book 33 Artists in 3 Acts. I spoke to a broad range of living artists – from superstars like Ai Weiwei, Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons and Grayson Perry, to lesser known 'artists' artists' and unheralded teachers, to ask them those two questions and to ask how they organise their lives in ways that allow them to summon up self-belief.

From the start of my research in summer 2009, I was keen to find an artist couple through whom I could investigate how artists handle competition, embrace muses, and the like. It was difficult to find a pair who enjoyed equal stature. Indeed, artist couples are usually governed by an unspoken agreement that one partner's career is more important than the other's. When I did interview artists with comparable levels of recognition, they were cagey and controlling. For example, one couple were happy to be interviewed apart but never together. Another would only speak to me at the same time. An added hurdle to casting the right couple was that I had to admire the artwork of both.

Thankfully, it didn't take me too long to encounter Carroll ('Tip') Dunham, a painter represented by New York's esteemed Gladstone Gallery, and Laurie Simmons, a photographer whose work I had studied as an art-history undergraduate. At first glance, their work has little in common. His paintings appear obsessed with formal structures, while her photographs seem driven to explore social codes (particularly issues of gender and domesticity). Over the years, however, the two artists have circled around similar subject-matter, lately focusing on sexually-charged images of lone women. Dunham's recent paintings often feature naked bathers with giant, almost smiling vaginas, while Simmons' photographs depict the lifelike sex dolls that the Japanese call 'love dolls' and others call 'Dutch wives'.

Luckily, Dunham and Simmons were fans of my previous book, Seven Days in the Art World (Sidenote 1 - Thornton's 'Seven Days' was split into seven chapters looking at the sociology of the contemporary art world, from auctions to the Turner Prize), so they knew where I was coming from and trusted that my intrusive questions weren't just prurient. I started visiting and interviewing them regularly. The conversations were always feisty; they weren't shy about disagreeing with each other in front of me. For example, one afternoon when I was sitting in the kitchen of their country house in Connecticut, I asked how their respective triumphs affected each other's self-esteem. "A rising tide lifts all boats," asserted Dunham > forcefully. "End of discussion! If it's good for her, it's good for me. There is no competition!" Simmons frowned and raised her eyebrows. "Can I give a more nuanced answer?" she asked. "We are both very ambitious for our work. Ambitious people feel competition. But even if I feel jealous, I never wish him the worse or want to tear him down. We do feel competitive with each other, but we do not begrudge each other's success." Dunham nodded in agreement, then added, "I could kill you with nuance".

During that conversation, the younger of their two daughters, Grace, called in from Paris (where she was on holiday with friends) while their elder, Lena, was napping in the TV room. Lena's film Tiny Furniture, which she had written, directed and starred in, had just secured a limited theatrical release. Her parents had given her the option: they would pay for grad school or a low-budget independent film. She chose the latter.

Over the course of the four years in which I researched 33 Artists, Lena went from being a university graduate to being the executive producer of her own HBO TV show, Girls, and a household name. Meanwhile, her parents trudged on, making their art, having shows, enjoying the appreciation of their peers and support of discerning curators. "We joke about being soldiers, marching forward regardless of how much flak we're taking," explained Dunham. "You need strategies to overcome resistance and negativity. You enter troughs where you don't feel motivated. These are battles."

"We also like the artist-as-farmer metaphor," added Simmons. "We get up early, work hard all day, and grow our stuff."

"The Roman citizen-farmer-soldier!" declared Dunham, who loves working a metaphor. "We will fight if needed but generally we'd like to tend our fields."

Some time later, I called Simmons for a scheduled catch-up, which just happened to be the morning after Lena won two Golden Globes – one for creating the best comedy series on television and one for performing in it. "Did you hear us screaming in Connecticut?" said Simmons, shortly after answering my phone call from London. She was thrilled that Lena was doing the kind of work she really wanted to do and was being so widely recognised for it. Nevertheless, having a famous daughter was affecting her sense of self. "It's only been a year that I've been known to the world as Lena Dunham's mother. I have to figure out how to navigate my life with this new information attached to me... Tip just casts it off." To be sure, Tip Dunham told me that he regards celebrity culture as "a fucked-up pile of ridiculous crap" with nominal interest as an "anthropological event". Reflecting on Lena's success, he marvelled at the differences between the "platform size" of a television show and a painting, but reaffirmed his interest in making works that "punch harder, go deeper, and do what paintings can do that other things can't". In his mind, he didn't have a choice because "anything else would be undignified".

Simmons enjoys the threat of potential indignity. She was then and continues to be working on MY ART, a feature film about an artist in which she plays the lead. The only other time that Simmons has acted in a feature and, indeed, played the role of an artist, is in her daughter's Tiny Furniture. "Nobody gets an artist right, even the child of two artists. Tiny Furniture left me feeling that something was missing," Simmons told me. "I will play the lead in MY ART, probably against everyone's better judgment, because it will create comparisons to Lena." In order to avoid repeating herself, Simmons forces herself out of her comfort zones. It's a means to the end of making fresh works. For Simmons, the agony of embarrassment pales in comparison to the "terror" of feeling invisible. "It is excruciating not to be seen," she explained. "Invisibility taps into something from my childhood. Other artists may have different neuroses, but the feeling of not being seen tips me over the edge."

"My mum is the biggest diva I've worked with in this business. She changed all her lines. She chose her own costumes."

From ‘33 Artists in 3 Acts’ by Sarah Thornton

"I was told that I should go on a date with Maurizio," says Lena Dunham incredulously about the artist who is 26 years her senior (Sidenote 2 - Each act of '33 Artists in 3 Acts' revolves around recurring characters who function as foils for one another. 'Act I: Politics' casts Ai Weiwei in opposition to Jeff Koons, while 'Act III: Craft' pitches the performance artist Andrea Fraser against Damien Hirst. In between, the familial theme of 'Act II: Kinship' gives rise to clusters. The entire Dunham-Simmons family is juxtaposed with Maurizio Cattelan, a Duchampian bachelor, and his brothers-in-crime, curators Francesco Bonami and Massimiliano Gioni. They are all, in turn, put into perspective by encounters with Cindy Sherman, who once described Simmons as her "artist soulmate".).

The writer-actress-director-producer has just ordered buttered scones and camomile tea in the quiet lobby of a hotel in the West End of London. The front desk knows her only by a pseudonym. She is wearing earrings in the shape of small bats and a slimming black jacket that she describes as a "pleasure to own" and looks much more beautiful than she does on Girls.

"When I was little, I thought the New York art world was everything," says Lena in her distinctly sweet and scratchy voice. "I can't remember a time when I wasn't aware of the mechanics. You go into your studio, you have studio visits, you have openings." Until the age of eight, she wanted to be an artist. "I thought that was what people's jobs were and I thought it was cool to be the same thing as your parents."

During adolescence, Lena decided that being a visual artist was "old-fashioned" and "small". It felt like "a trap". In her view, the audience for art is "rich people" and "those who wander into the white box". In a world of new communications technologies that have the power to reach millions, "it didn't seem germane". Being an artist felt stifling in other ways, too. "My dad is such a verbal, funny person," says Lena, "but he does this job where, for the most part, talking doesn't exist."

When Girls first launched, bloggers attacked Lena for benefiting from nepotism, as if Carroll Dunham ran HBO or Laurie Simmons had sway in Hollywood. "People were complaining before they had figured out who my parents were," she explains. Shortly afterward, the internet was flooded with articles about Lena's "not-so-famous" artist parents. "No one is going to give you a TV show because of your parents," she declares as she slips off her shoes and swings her legs up on to the velvet couch. "It is just not going to happen."

Growing up in an artistic household, however, had positive effects. > "I was given the tools, the space, and the support to do whatever I wanted," she explains. "New approaches to old problems were encouraged." Lena thinks about creativity as "an ineffable bug that takes you over but also something that you can learn". The idea that you need to be inspired is unhelpful, if not obstructive. "My parents taught me that you can have a creative approach to thinking that is almost scientific," she explains. "You don't have to be at the mercy of the muse. You need your own internalised thinking process that you can perform again and again."

Although Lena abandoned her desire to be an artist in the strict sense, her definition of an artist could be applied to her current role. "As an artist," she says, "you get the opportunity to write the world – or create the world – that exists in your fantasies. It's a really beautiful thing to do."

From afar, Lena's work in TV might look closer to her mother's collaborations than to her father's solitary practice of painting, but Lena doesn't see it that way. "Everything that I do comes out of writing. It's the genesis point," she explains. "You go within yourself, wrestle with your demons, scribble some stuff up and come out with a vision of what the world is like. It is closer to being a painter." By contrast, Lena views being a director as akin to being a photographer because both are "managerial and social". She shines as she admits: "It rescues you from the lonely life of a writer".

Lena is also a producer. Ironically, in television, the term 'producer' is used interchangeably to describe either 'the creator' or a person with the financial skills to raise and allocate money. It's hard to imagine that happening in the art world, where artists who act like dealers are often viewed suspiciously.

When it comes to artists and actors, Lena finds few parallels. "You can't indulge your private creative brain when you are following a script," she says. An actor is more like a musician in an orchestra. "When I am acting, I don't feel like a boss," she explains. "I feel like I am working in service to myself as a director. And I wish every actor was thinking that way, too!"

When Lena cast her mother as a dealer in Girls, Simmons behaved on set like the artist she is. In an interview broadcast after the programme, Lena said, Simmons is "the biggest diva I've worked with in this business. She changed all her lines. She chose her own costumes. She gave direction to other actors as well as the DP." Lena wavers comically between smiling and frowning when I confront her with her words. "I recognised that I was casting someone who can't be complacent. It's not in her DNA," she explains. "My mum always said to me, 'The talent is allowed to act weird'. She embraces the idea that, as an artist, she can act a little persnickety and say exactly what she wants."

Your mother told me that she uses embarrassment as a tool in her creative process, I say, leafing through the transcript of an old interview with her parents. "If I am starting to feel like I am alone with my pants down in my studio," said Simmons, "I think, OK, let's keep travelling slowly in this direction." Girls is full of humiliating situations. Do you use discomfort as a means of gauging the emotional importance of an idea, I ask.

"The kind of shame I deal with in my work is about returning to the scene of the crime with all my senses operating," replies Lena. "I agree with Woody Allen's theory that tragedy plus distance equals comedy." The writer-director-actress describes herself as "insanely close" to her family so it is difficult for her to get perspective on their influence. "My dad is a little more consistent and unwavering in his work process and he's more apt to display it to those around him," she says, "whereas my mum goes away, hands flying, comes back, and something has been made."

Lena sips her tea delicately, with the porcelain cup in one hand and its saucer in the other. She is calmer and more refined than her persona in the series, whose tagline is 'Almost getting it kind of together'. Indeed, Lena sits a few rungs higher up the class ladder than her Hannah character.

Lena's comfort with her public persona is one area where she and her father, despite their affinities, drastically diverge. When Dunham refused to be in Tiny Furniture, Lena wrote him out of existence. As he told me, "Father, what father? The kid was created by parthenogenesis or something." Lena is adamant that the film's "complete avoidance" of a father figure was "not in any way a 'fuck you' to him". Rather, she felt that no one else could embody him.

Despite her intimacy with artists, Lena accepts that she has trouble depicting them. Among the quirky, complex male characters on Girls is an artist named Booth Jonathan, who is portrayed two-dimensionally as an arrogant egotist. One of the leading female characters, Marnie (played by Allison Williams), compares him to Damien Hirst and then has funny-gruesome bad sex with him. "Artists are hard for me to write," admits Lena. She imagines her "father's disapproval when something doesn't feel real" and she doesn't want to contribute to the comic cliché that contemporary art is a con that dupes through pretension. "Booth Jonathan," she admits, "was based on douche-y college boys more than any of the cool, smart artists I've met through my parents" µ

‘33 Artists in 3 Acts’ by Sarah Thornton is out now (£20, Granta)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments