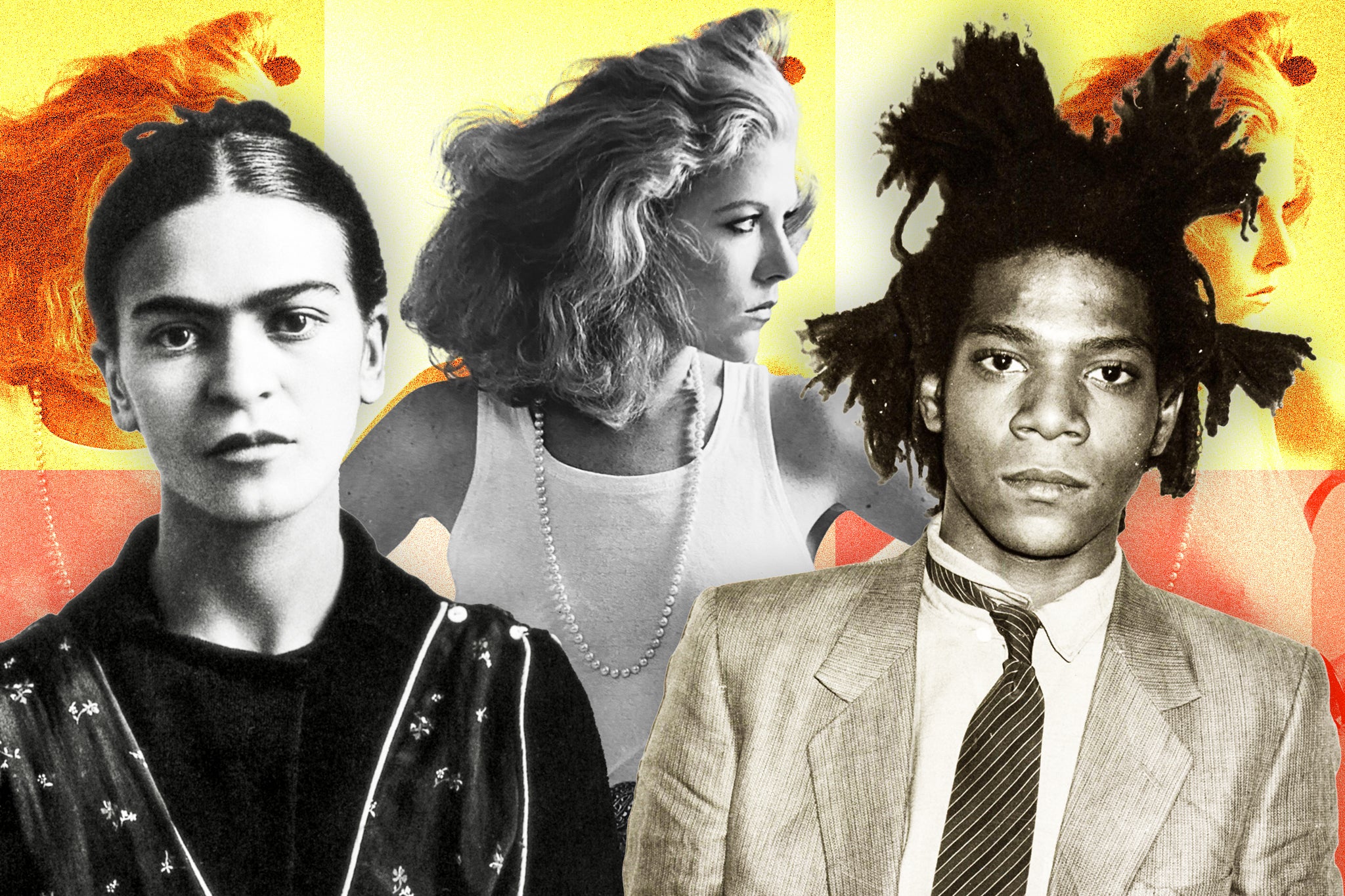

Growing up in the shadow of Frida Kahlo, partying with Basquiat: my life with art’s A-list

As a child she splashed around in Frida Kahlo’s bathtub, in a house that still smelt of the artist’s oil paints. At 16, she partied with Madonna and Basquiat in New York, living off ‘coffee, coke, Coca-Cola and Camels’. Jennifer Clement tells Chloe Ashby why she had to write about coming of age with a set of art superstars

On hot May days in the Sixties, when Jennifer Clement was a little girl, she used to bathe in Frida Kahlo’s tub. Together with Ruth María, Diego Rivera’s granddaughter, she would fill it with water and treat it as a swimming pool, a place in which to cool off. Back then in Mexico bubble bath didn’t exist, so they would tip in half a bottle of old shampoo and kick and stir and churn. They didn’t know that the bathtub had once contained the great Surrealist’s body, too, and was preserved in a special and wild self-portrait.

“It was just normal life,” Clement tells me from her second home in San Miguel de Allende, a small storied city in the Mexican highlands. We’re talking via our screens ahead of the release of her new memoir, The Promised Party: Kahlo, Basquiat & Me. Comprising brief and rhythmic chapters of anecdotes and recollections, it’s a tale of two cities, as well as a tale of the writer as a young woman, from her bohemian childhood in 1960s and 1970s Mexico City to her early adult years in 1980s New York City. It’s also a tale of the artists and writers she met along the way, and those whose legacies lingered both physically and in her imagination.

Clement, eloquent and assured in conversation, is the former president of the worldwide writers’ association PEN International, as well as the author of multiple books, from novels to poetry collections. The Promised Party sees her return to some of the territory of perhaps her most popular publication: her first, Widow Basquiat, a memoir about Jean-Michel Basquiat’s relationship with muse and mutual friend Suzanne Mallouk – Dua Lipa has cited it as one of her favourites. In person, Clement is the same as she is on the page – curious and candid – and eager to talk: this is her first interview about the memoir.

We begin with her parents move to Mexico in 1960; her older brother was almost three and she was a baby. Her mother was a painter from Nebraska, her father an engineer and self-made intellectual from a Jewish family in New York. They just so happened to land on a street two blocks from Kahlo and Rivera’s house and studio, before it had become the museum it is today; the artist couple had died some years before, but the rooms still smelled of their oil paints, turpentine and cigarettes. Rivera’s daughter, Ruth, lived there with her children, Pedro Diego and Ruth María, who became Clement’s first friend. They went to a British school together with Gabriel García Márquez’s boys and Leonora Carrington’s kids.

Clement’s childhood was filled with art, books and theatre; from a young age she wrote poems and danced, and on weekends her father would take the children to the opera. It was, she writes, a childhood “steeped in Surrealism”, which was part of the impetus for her to write The Promised Party. “I felt like I was covered in the dust of the golden age of Mexican muralist and surreal art and ideas, and that I needed to write about it,” she says. “Surrealism isn’t just about crazy paintings. As [Mexican poet] Octavio Paz said, it’s also a spiritualist movement, a way of being in the world, where love is a centrepiece, and tolerance and reason.”

The Mexico City of her childhood had a dark and prickly undercurrent. Clement writes about rabid dogs and nightwatchmen, one of whom, an acquaintance, was knifed and killed. She describes the terrible brutality of the police force: “We knew there was theft, corruption, drug trafficking, the trafficking of women and girls, torture and murder. People disappeared.” A chapter is dedicated to the harassment she experienced daily as a girl – being grabbed by men on the street, having her hair pulled, encountering exhibitionists. Thanks to her father’s involvement in the Civil Rights Movement and her mother’s ground-breaking work on the birth control bill, she and her two siblings (a younger sister was born a couple of years after they arrived in Mexico) were politically aware. “I think they instilled in us a consciousness of social service and doing good in the world,” says Clement, who is certain that the foundations of her becoming president of PEN were “grounded in that – the idea that you serve, that you give back”.

In 1976, aged 16, Clement left Mexico City and went to boarding school in the US, and two years later enrolled at NYU to study dance before switching to literature and anthropology. And, once again, in what she calls “a stroke of luck”, she found herself moving in circles with artists and writers whose names nobody knew at the time, but who are now famous the world over. Madonna? “She was just a bartender.” Jean-Michel Basquiat? “He was just the not-so-great boyfriend of my great girlfriend – we all know how that goes,” she says, with a wry smile.

Clement met Basquiat, of both Haitian and Hispanic heritage, through that great girlfriend, Suzanne Mallouk, who had bought a one-way ticket from her home in Ontario, Canada, to New York City in 1980. In Widow Basquiat, Clement describes their passionate love story, and in The Promised Party she revisits the way Mallouk inspired several of his paintings, and how the pair were always breaking up and getting back together. “There was a good feeling between us because he was a good person and I think he was happy that Suzanne, who’s quite eccentric, had a good friend,” Clement tells me. “We also related as Spanish speakers and as Latinos. He used to ask me to recite all the television shows that were dubbed in Mexico, and then he would write down words and phrases. I was a strange Latina, and he was a strange Latino in a way, but we both were.”

In New York, Clement never slept, and lived on “coffee, coke, Coca-Cola and Camels”. She gave poetry readings at Keith Haring’s Wednesday poetry nights at Club 57 on St Mark’s Place. She worked as a waitress at Max’s Kansas City, where bands such as the Ramones and Blondie played on Thursday nights. She served the glamorous performance artist Colette Lumiere martinis before they became friends. After a shift, she and her great friend Lili Dones would go to CBGB’s or Studio 54. (Clement was sure that Dones was a member of anonymous feminist art collective the Guerilla Girls: “She always had inside information, which she’d tell me followed by, ‘Forget what I just said’.”) It was on a night out at Studio 54 with her friend Hal Ludacer – “the most beautiful creature in New York” – that she first met Andy Warhol. She writes: “Andy was the worst. He really harassed Hal, as if his fame and fortune gave him rights. We kept away from Andy as much as possible.”

The fantastic freedom of life before Aids never really came back

I ask Clement what it felt like, to be a part of this scene, to live among these now-starry characters and, in a way, to be the person taking notes. She tells me that’s another reason she realised she’d better write it all down – “because I’d been a witness to so many things”. Also, to commit to the page two worlds that are gone. “Mexico is no longer that Mexico, and New York is no longer that New York,” she says. “The fantastic freedom of life before Aids never really came back.” Her neighbour, the otherworldly German-born singer Klaus Nomi, was the first person she knew who died of the disease that ravaged the world.

“So, yes, I felt this need to bear witness,” she continues. “I also felt a desire to explore who I am and how I came to be this way, what formed me intellectually.” The people and ideas she encountered along the way.

Aged 27, Clement returned to Mexico City, which is where The Promised Party ends. She writes: “As every other Mexican abroad, from the richest to the poorest, we’re all thinking about Mexico.” She tells me it never crossed her mind to stay in New York or to move elsewhere in the United States. That she went on to have her children in Mexico – they’re Mexican. “I think that many people, but especially artists and writers, are very affected by Mexico. Something happens here,” she says. “There’s the anarchy. There’s the feeling of being closer to the dead than to the living, which is real, it’s not a cliché. And then there’s the magic – which is that there’s going to be a miracle, you’re going to win the lottery. There’s possibility.”

‘The Promised Party’ is out on 18 January, published by Canongate (£16.99)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks