How Jack Kerouac left a legacy of rarely seen 'beat paintings'

Just as Kerouac’s work featured real people from his life and adventures turned into fictional pastiches, so did his art

We think of Jack Kerouac and we think of writing – urgent, spontaneous writing, a rush of Proustian prose, unreliable memoirs of a time of change and upheaval in mid-20th-century America.

We think of On The Road, that astonishing yet divisive piece of work bashed out on a long roll of paper, we think of the contemporary, drug-and-booze soaked image of a romanticised latter day cowboy roaming the highways of an America in flux. We think of the man who ushered in the Beat Generation, and who died, middled aged and reactionary, of cirrhosis of the liver.

What we don’t often think about when we think of Jack Kerouac is the artist.

Few of the many biographies of Jack Kerouac, who was born in 1922 and died in 1969, even mention his paintings or talent for art. And yet, alongside his incredible body of written work, he also left behind a huge amount of rarely seen artwork.

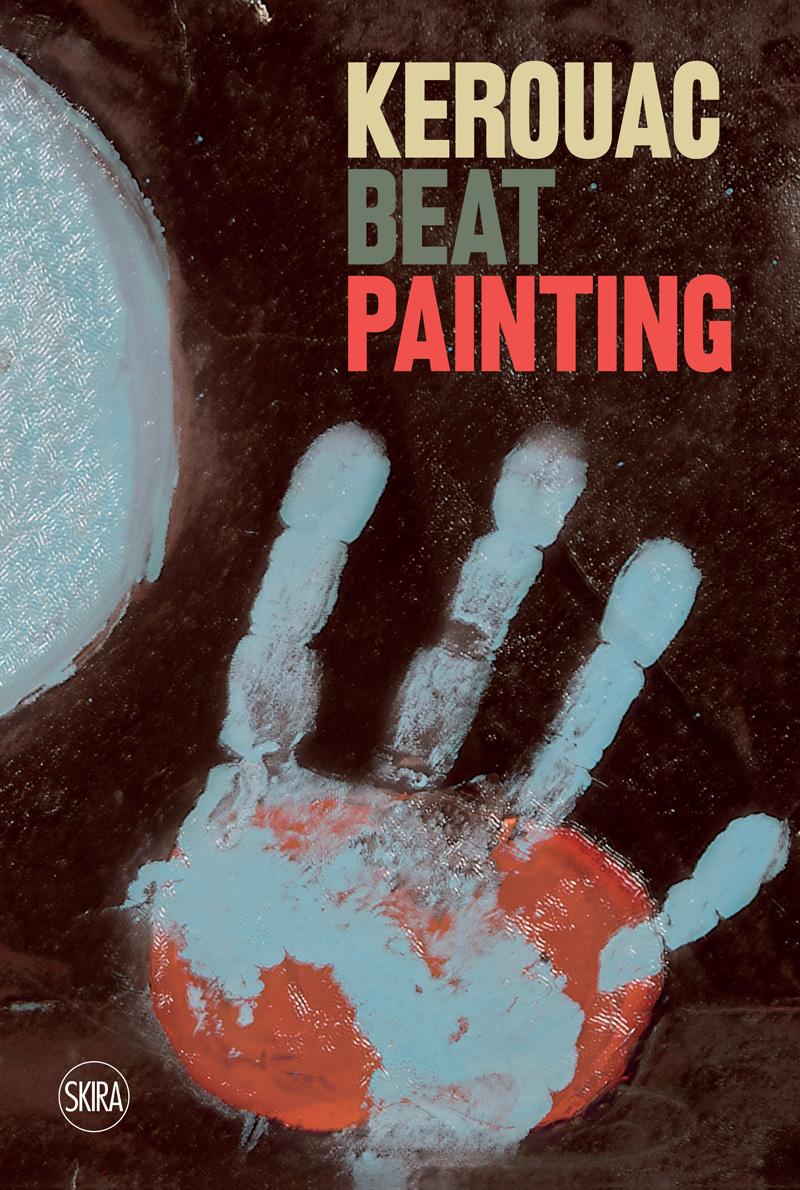

Earlier this year, the Museo Maga in Gallarate, a town just outside Milan, collected as much of Kerouac’s artwork as it could find and staged an exhibition of more than 80 pieces. A new book has also been published, featuring some of the artworks, many of them seen for the first time.

John Shen-Sampas, the son of Kerouac’s brother-in-law John Sampas (his sister Stella Sampas, was Kerouac’s third wife, and they married in 1966) wrote an introduction to the exhibition. Kerouac's brother-in-law was one of his oldest childhood friends, growing up with him in the town of Lowell in Massachusetts. He died last year aged 84.

Shen-Sampas said that, while Kerouac was never really known for “his artistic endeavours in painting and drawing”, when he died he “left a trove of portraitures, drawings and sketches behind”.

According to Shen-Sampas, Kerouac’s artistic leanings emerged when he was just nine years old and he drew his first self-portrait. He later said that he would rather be a painter than a writer, and when he was writing, he filled his notebooks and journals with sketches and doodles.

Famously, Kerouac was unhappy with the cover his publishers gave his very first novel, The Town and The City, when it was published in 1950. That first novel was a very different beast from the work he became known for – more of a family saga in the mould of Kerouac’s hero and novelist Thomas Wolfe. The cover attached to it was a pastoral, gentle affair that Kerouac wasn’t too fond of, so when he’d written On The Road and before it was eventually published after a five-year battle in 1957, he designed his own cover.

It was a rough pencil sketch of himself embarking on an infinite road, the title of his work diminishing in perspective towards the vanishing point, with the accompanying typewritten note to potential publisher A A Wyn saying, “I submit this as my idea of an appealing commercial cover expressive of the book. The cover for The Town and the City was as dull as the title and the photo backflap.”

Neither the cover nor the book appealed to that particular publisher at that time, but it wasn’t long before Kerouac did find a publisher for On The Road, and his reputation was cemented as one of the most important writers of the second half of the 20th century.

Meanwhile, he continued to draw, and paint, and if that quick design for a book cover that never happened was rough and ready, his later work suggests a far more serious attempt at artistic endeavour.

The book begins with a series of portraits of people Kerouac knew or admired. They also highlight Kerouac’s complicated spirituality; brought up a Catholic, he later embraced Buddhism and developed an almost “holy fool” persona.

One of his early, post-On The Road paintings is a portrait of Cardinal Giovanni Montini, who would later become Pope Paul VI in 1963. Kerouac never met him, but based his oil painting on a photograph in Time magazine. It’s an expressionistic piece, almost medieval in its execution.

Just like Kerouac’s work featured real people from his life and adventures turned into fictional pastiches, so did his art. Another oil on canvas piece from the same period is Woman in blue with black hat, the subject leaning on a wall and smoking a cigarette. It’s an image of the character Joan Rawshanks, who appears in his novel Visions of Cody, and who was based on Kerouac seeing the Hollywood femme fatale Joan Crawford filming in the streets of San Francisco in 1952.

Kerouac was introduced to the New York art scene, specifically the Expressionist community, by artist Dody Muller in 1959. He liked veering between styles, from using oils to scribbled pen drawings, to watercolours that plumbed his religious leanings. But are they actually any good?

“It would be wrongheaded to read these artworks using an art critic’s traditional method,” says Sandrina Bandera, one of the curators of the exhibition and editor of the book Kerouac: Beat Painting, which has just been published. Why? Because Kerouac was not wholly an artist, but almost a pop-cultural phenomenon whose paintings and drawings were, as Bandera puts it, “an essential part of that potent entity known as Jack Kerouac. These works are like the limbs of a single body spinning on its own axis, so dynamic that it needs an abundance of different tools to express itself.

“It would be a serious mistake to consider these illustrations and sketches as divorced from the artist’s writings, judging them, that is, from merely a stylistic point of view from that of the subjects they portray.

“The artworks are an integral part of the writings and should be interpreted in the same way as Kerouac’s own writing style, for which he coined the term ‘spontaneous prose’: the composition of sentences by association, in a stream of words free from syntactic constraints and with all the immediacy of a rushing river.”

In other words, how you get on with Kerouac’s artwork will probably depend on how you view his writing. Almost 50 years after his death, Kerouac is, on the one hand, fêted as an almost supernatural genius, and on the other, disparaged in the way best epitomised by Truman Capote’s droll put-down of Kerouac’s work: “That’s not writing, that’s typing.”

Interestingly, Kerouac did an oil portrait of Capote in 1959, around the time the Breakfast at Tiffany’s author was directing his vitriolic attacks against the Beats in general and Kerouac in particular. It’s dark and brooding, a painting with – as Bandera describes it – “a dynamic, almost violent quality.” A direct response to Capote’s criticisms? “Probably,” says Bandera.

Perhaps the most interesting section of the book to fans of Kerouac’s work will be the one that gathers, what the curators call, his “Beat Paintings”, ones that are infused with the urgency and themes of his writing.

Born into a French-Canadian family, Kerouac always felt an affinity with France (one of his later books, Satori in Paris, details his search for his Breton heritage) and many of the paintings in this section are influenced by surrealism and abstract art.

According to Bandera, Kerouac was almost as serious about his art as he was about his writing, especially from 1952 onwards, when he entered the phase where he would begin writing what would become his most well-known works.

Indeed, he drew up a “manifesto” for painting, a set of rules which he followed, the handwritten note of which, written in 1959, was presented at the exhibition in Italy this year.

“Only use brush,” advocated Kerouac. “No knife to mash and spread and obliterate brush strokes. Only use brush spontaneously, ie without drawing, without long pause or delay, without erasing … pile it on.” And perhaps the most typically Kerouacian advice from a writer who knocked out his magnum opus On The Road in a three-week writing jag: “Stop when you want to ‘improve’ – it’s done.”

Whether Jack Kerouac’s paintings and drawings have any artistic value is probably as vexing a question to many as whether his writing is actually any good. Should we even be asking the question, even be probing the inner meaning of Kerouac’s paintings? Perhaps the final word should go to the man himself: “An art dies when it describes itself instead of life.”

"Kerouac: Beat Painting" edited by Sandrina Bandera, Alessandro Castiglioni and Emma Zanella is published by Skira Editore, priced at £30

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks