Indigenous Australia at the British Museum: It's time to give the Aboriginal art back

The artworks in the British Museum's new exhibition may be striking, but even looking at them colludes in an act of theft, argues Zoe Pilger

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 1821, a teenager named Mary Palmer was convicted of tying up and robbing a gentleman in Whitechapel, London. She was my great-great-great-grandmother. While her gang was sentenced to death, Mary was saved by the fact that she was pregnant. She was deported as a convict to the penal colony of Australia, which was deemed terra nullius, nobody's land, by the British colonial authorities.

Of course, Australia wasn't uninhabited; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people had lived there in harmony with the earth for over 40,000 years. The idea of emptying the prison population of Britain into a country on the other side of the world, and thereby creating a new nation, is surreal – a dystopian experiment. But it was real, and it was violent.

The rape of indigenous culture by the British colonisers is bound up with the acquisition of indigenous art by the British Museum, which was founded in 1753, not long before the British flag was raised in Australia in 1788. The museum quickly filled with the spoils of empire. Now activists are fighting for the return of the 6,000 indigenous objects owned by the museum on the grounds that they were plundered.

Many are included in a new exhibition, Indigenous Australia: Enduring Civilisation, which opens on Thursday at the British Museum. To look at these beautiful baskets, shields, spears and masks is arguably to collude with the on-going denial of indigenous rights. The descendants of the people who made them want them back. Therefore they should go back.

Indeed, this exhibition is half in denial. It both acknowledges the violation of the indigenous people and censures that violation. It uses terrible metaphors: the histories of the indigenous people and the colonisers are "entangled", "interlinked", born of "encounters" and "misunderstandings". These words are ways of repressing the fact that white Australia is founded on murder. The drama and dignity of the story of indigenous colonisation and resistance is thereby muted. This also has the effect of draining the exhibition of vitality – it is quite dull, which indigenous art emphatically is not.

Aboriginal art is rooted in the Dreaming, a mythic time when creation ancestors brought into being all that exists, and moral and spiritual law began. The Dreaming is not past, but past, present and future all at once. Aboriginals believe that time is cyclical, not linear. Like the people, the objects are inseparable from the country. To separate the people from the country is to separate them from themselves. Similarly, the dispossession of these objects to institutions like the British Museum is not simply a political issue, but an existential one. It undermines the very nature of their being.

Protests are expected at the opening due to the inclusion of two works in particular: a rare bark etching of what the museum has controversially described as a kangaroo hunting scene, and a bark figure of an emu, made around 1854. These were acquired (according to the catalogue, there is no record of how) from the Dja Dja Wurrung people of Victoria by a Scottish settler, John Hunter Kerr (1821-1874), and later became part of the British Museum's collection. In 2004, they were lent to Museum Victoria in Melbourne for an exhibition, Etched on Bark 1854. Legal action was brought by the Dja Dja Wurrung people to stop the works' re-exportation to Britain, but this failed, and in 2013, the Australian government introduced the Protection of Cultural Objects on Loan Act.

This raises questions about the responsibility of colonial institutions in post-colonial times. The British Museum does not want to set a precedent for the return of objects acquired during empire. In this case, they would have to return the Elgin Marbles to Greece, and many other works from the collection.

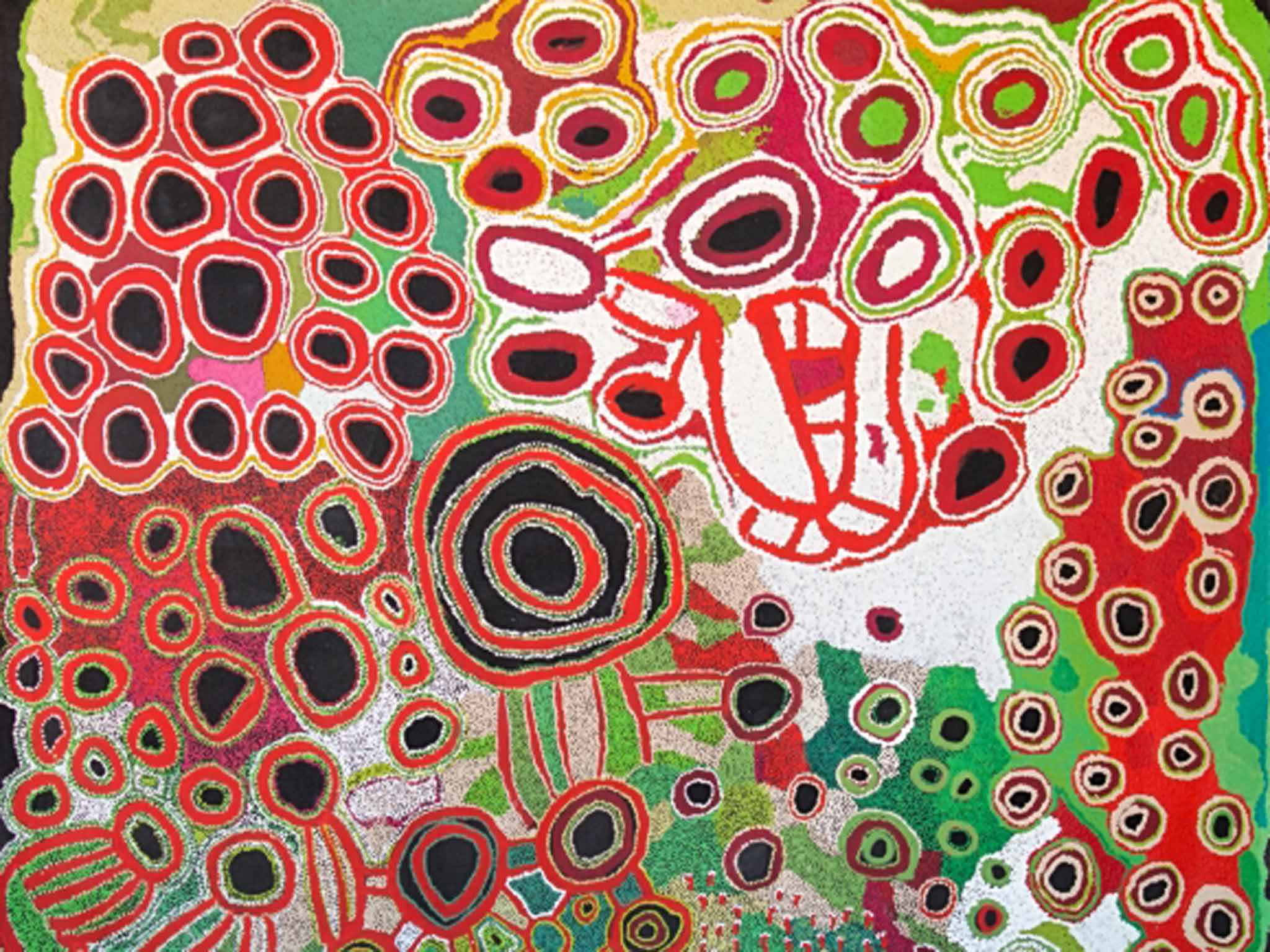

Some of the most striking works in the exhibition are contemporary. Kungkarangkalpa (Seven Sisters) from 2013 is a large acrylic painting by six senior Spinifex women of the Great Victoria Desert. It is a joyous assemblage of black dots and red lines, of luscious green and pure white background. Each shape corresponds to an element in the landscape. The work refers to the story of the Seven Sisters from the Dreaming: a group of women were pursued by Nyiru, a lustful man disguised as a python. They escaped into the sky and transformed into stars, which enabled the people to find their way across the country.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Spinifex land was used for British and Australian nuclear testing. A clue to the bias of this exhibition is shown in the wall text; it states that the Australian authorities removed the Spinifex people from their land. In fact, they were not sufficiently warned in advance, making them vulnerable to radiation sickness.

Another striking work is Yingarna (The Rainbow Serpent), which was created before 1978 and is made of natural pigment on bark by the senior artist Bilinyara Nabegeyo (1922-1978) of the Kunwinjku people of the western Arnhem Land. It shows another story from the Dreaming: the powerful female rainbow serpent who lives in lagoons or underground. Here she appears to have swallowed a series of white people, who are shown inside her. Outside her, brown people swim. This may not refer to race; the precise meaning of the works is often not disclosed to people outside the community.

Art is one of the few aspects of Aboriginal culture that has been historically prized, first as ethnographic curiosities and later as tourist souvenirs and symbols of Australian nationalism. The Aborigines themselves have seen little reward, however. Artworks have been bought by white traders at a price lower than market value and resold, or worse, exchanged not for money but alcohol. This is disgraceful as rates of alcoholism are high in the Aboriginal community.

The inclusion of the memorial pole, Barama / Captain Cook at the Sacred Waterhole of Gangan (circa 2002), should be viewed with suspicion. Made of pigment on wood, it is the work of Gawirrin Gumana of the Dhalwangu people in the northeastern Arnhem Land. One side of the pole is painted with the face of Barama, a creation ancestor who brought into being the laws of nature and society. On the other side is the face of Captain Cook. The symbolic coexistence of the laws of the Dreaming and those of the coloniser is presented by the exhibition as a vision of harmony and forgiveness. According to the wall text, the design is "a gesture of historical and political generosity." But why should the artist be generous?

There are hints at a more brutal history. A photograph from the late 19th century of Aborigines chained at the neck, being led to trial for cattle theft, is difficult to look at. Also displayed are the spear and boomerang collected during the hunt for Jandamarra (1873-1897), an Aboriginal resistance fighter of the Kimberley region. He was eventually shot. His head was sent back to England and displayed in a gun factory to demonstrate the brilliance of English weapons.

While this information is given in the exhibition, the extent of Jandamarra's achievement is played down. It seems safer to celebrate the creation ancestors of the Dreaming, rather than real historical figures such as Jandamarra, who represents the possibility of indigenous people fighting back with force.

Indigenous Australia: Enduring Civilisation, British Museum, London, 23 April to 2 August (britishmuseum.org; 020 7323 8181)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments