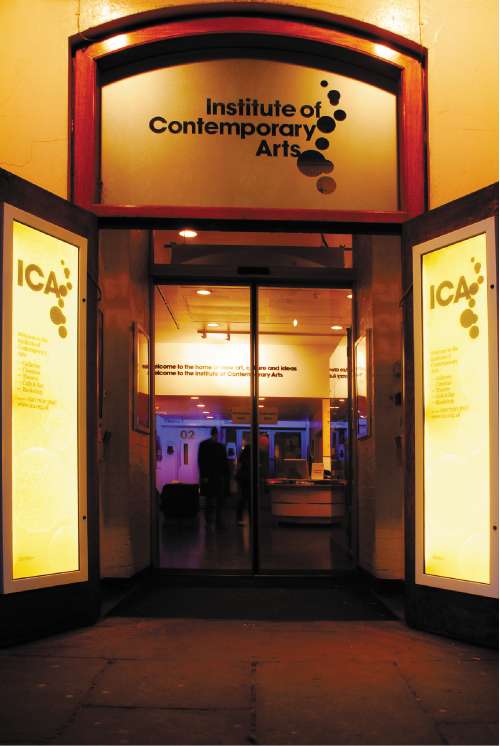

In praise of the ICA, home of the avant-garde

Last night's concert by REM celebrated the sixtieth anniversary of the Institute for Contemporary Arts. Ciar Byrne and Emily Dugan pay tribute to an organisation that remains as modern as ever

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When REM stepped out at the Albert Hall last night in honour of the 60th birthday celebrations of the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), it can be safely assumed that Ivan Massow was not present among the assembled well-wishers. Six years ago Mr Massow, a businessman, was forced to resign from the ICA's board of directors after making outspoken and deprecatory remarks about modern art.

He had to go. For better or for worse, the modern, the challenging, the outré and even the downright odd is and always has been the raison d'etre of London's most determined defender of the avant-garde.

The first exhibition staged by the ICA, in 1948, was held not in the splendid surroundings of The Mall, but in a dingy Oxford Street basement. Entitled "40 Years of Modern Art", the exhibition displayed some of the greatest works in the burgeoning Cubist movement alongside a lavish range of international artists. It was an attempt to move away from the orthodoxies and conservatism of the London art scene, a desire which has maintained its intensity for the next six decades.

The REM gig is being accompanied by an exhibition of photographs of the group at the ICA's gallery. "There isn't a historical connection," admitted Ekow Eshun, the current artistic director of the centre. "But you could say there's been a history of mutual admiration." He added that REM's interest in artistic projects outside of the purely musical, such as the lead singer Michael Stipe's schooling in video art, provided a connection.

The seeds of iconoclasm were sewn in 1947, when a collection of modernist artists and thinkers sought to deliver a stark, exciting alternative to the post-war austerity and mainstream fare on offer at galleries elsewhere; this was to be a private members' club that would revolutionise the way Britain thought about art.

Led by the poet, literary critic and philosopher Herbert Read, the surrealist painter, poet and art historian Roland Penrose, and the artist Eduardo Paolozzi, the group founded the ICA with the intention of breaking down barriers between different artistic disciplines and presenting an ever-changing series of talks and exhibitions, in contrast to the stultifying permanent collections of the existing national institutions.

Mr Eshun said: "The story is the coming together of the great modernists who were around in Britain in that period. It was a celebration of pre-war modern art in the post-war era. Very quickly it became a gathering point for advocates and supporters of modernism."

Herbert Read was perhaps the most outlandish of the three founders. An anarchist, he wanted the institute to be "an adult play centre", where free-thinkers of the arts and science world could meet. This statement was no joke, for in the years after the Second World War, he believed that aggression could be "kept in check via sublimation – namely through play".

In his ICA manifesto, Read talked about creating a place that didn't have a fixed culture, although he admitted he and his colleagues might be mocked for their "naïve idealism".

Penrose and Read had already established themselves on the cutting edge of the art scene after collaborating on the 1936 London International Surrealist Exhibition – a show which has since been credited with launching the British surrealist movement.

The first major art phenomenon to be pioneered by the ICA, however, was the British pop art movement. This was largely down to the Paolozzi, who was becoming established as a pop artist in his own right.

In the 1950s their first exhibition space was in Dover Street, Mayfair, where they held some of the first major pop art exhibitions. From this small building they also pioneered the careers of modernist classical composers, such as Stravinsky and John Cage, and began to screen arthouse films chosen by members. Over the years, T S Eliot, Jackson Pollock, Jacques Derrida, Yoko Ono, Vivienne Westwood and Zadie Smith have also played a part in shaping the most distinctive art venue in Britain.

In the 1970s the ICA became notorious, and wildly unpopular with the political right, for its radicalism and ever-more daring commissions. The tabloids had a field day when the gallery hosted an explicit exhibition on prostitution. A battle ensued over the legitimacy of public funding for material so challenging to the public taste. Eventually, in one of the ICA's rare defeats, the show was forced to close within four days of opening. Since then, however, an invitation from the ICA has been a cultural springboard for generations of artists such as Damien Hirst, Luc Tuymans and Steve McQueen, who all had their first solo shows there. In the 1990s the gallery also served as a starting point for many Young British Artists, most notably Jake and Dinos Chapman who staged their first show there in 1996, Chapman World.

Then there has been the music. It is no accident that REM were keen to play the anniversary show. Stipe and his bandmates are among the many international artists who have sought inspiration at the institute, which has been at the forefront of the music scene since the 1950s. The Clash and The Smiths both played early gigs there while many other venues let them languish in unsigned obscurity. The Stone Roses, Franz Ferdinand and Scissor Sisters have also been showcased in its 300-capacity theatre. Continuing the spirit of musical innovation, last July the ICA hosted a series of 31 free gigs by performers including Amy Winehouse, Mika and Stereophonics, with tickets allocated by prize draw.

In 2008, the shoals of tourists continue to float by the ICA en route to Buckingham Palace, most with no inkling of the cultural riches housed within the relatively modest frontage. Stopping to investigate, they would discover a vibrant programme of exhibitions, films, concerts and talks – including studies of Brazil's urban beaches; a documentary about a 93-year-old barber in Beijing; the film-maker Peter Greenaway telling stories about storytelling and indie bands playing to intimate audiences.

Mr Eshun believes that staying true to its roots has helped the institute thrive. In the past two years, visitor numbers have soared 24 per cent to half a million and membership has risen.

He explained: "The purpose of an institution like this isn't to be a museum, but it's not about storming the barricades any more. It's about the most exciting, innovative and urgent creativity. There's a need to keep rethinking what's happening.

"When you don't have a permanent collection, you have a real responsibility to think about what is a contemporary moment. One of the reasons the ICA still exists and is still important is because we have exhibitions and talks programmes, major thinkers and artists and writers. The combination of all these different spheres means we have an ongoing conversation with the public."

The arrival of Tate Modern in 2000 might have been seen as a rival for the ICA's audience, but Mr Eshun insists that has not been the case.

"The Tate has grown the audience for art," he said. "Also, we do different things. The ICA excels at showing artists at an early stage in their careers. We don't do mid-career retrospectives."

That theme will play a central part in the remaining anniversary celebrations.An exhibition opens in May of 60 young artists. Each artist will stage a two-week solo show over a six-month period, providing a career launchpad like those offered by the gallery to so many of today's most famous artists.

"We're bringing on to the public stage artists who we think have a significant role to play in the future," said Mr Eshun. "For me that's a really exciting statement of intent."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments