Helen Muspratt: The woman who photographed the Cambridge spies

As an experimental photographer, she pushed boundaries while shooting the cream of society. At home, she was the principal breadwinner. And all this in the 1930s. As a new book by her daughter reveals, Helen Muspratt was a true pioneer

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Cambridge in the 1930s was a hotbed of left-wing and academic brilliance, dominated by some of the greatest names of 20th-century intellectual life (the economist John Maynard Keynes, the writer CP Snow, the biochemist and Nobel Prize winner Dorothy Hodgkin) as well as some of the most notorious: the spies Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean, the art historian/spy Anthony Blunt.

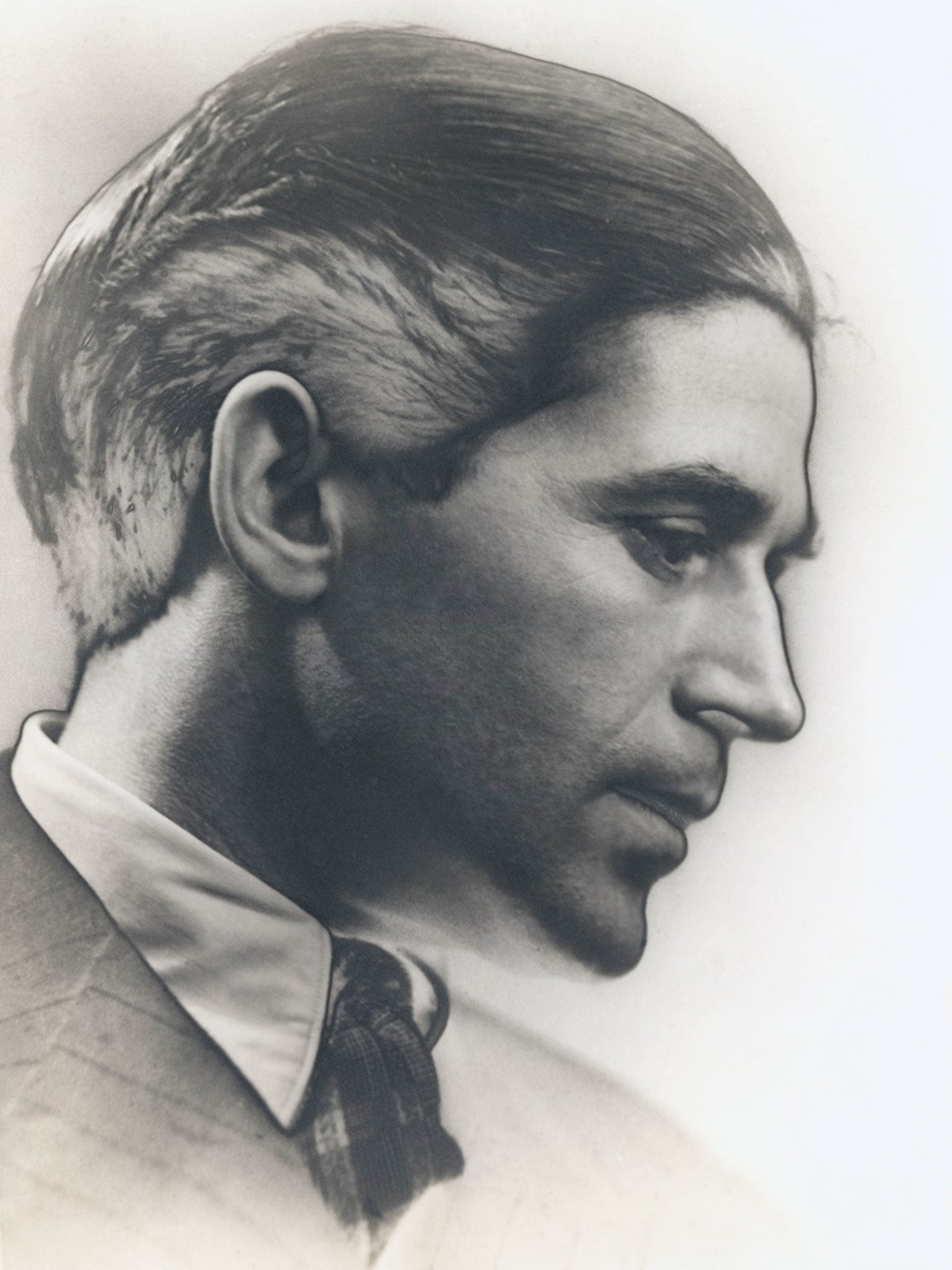

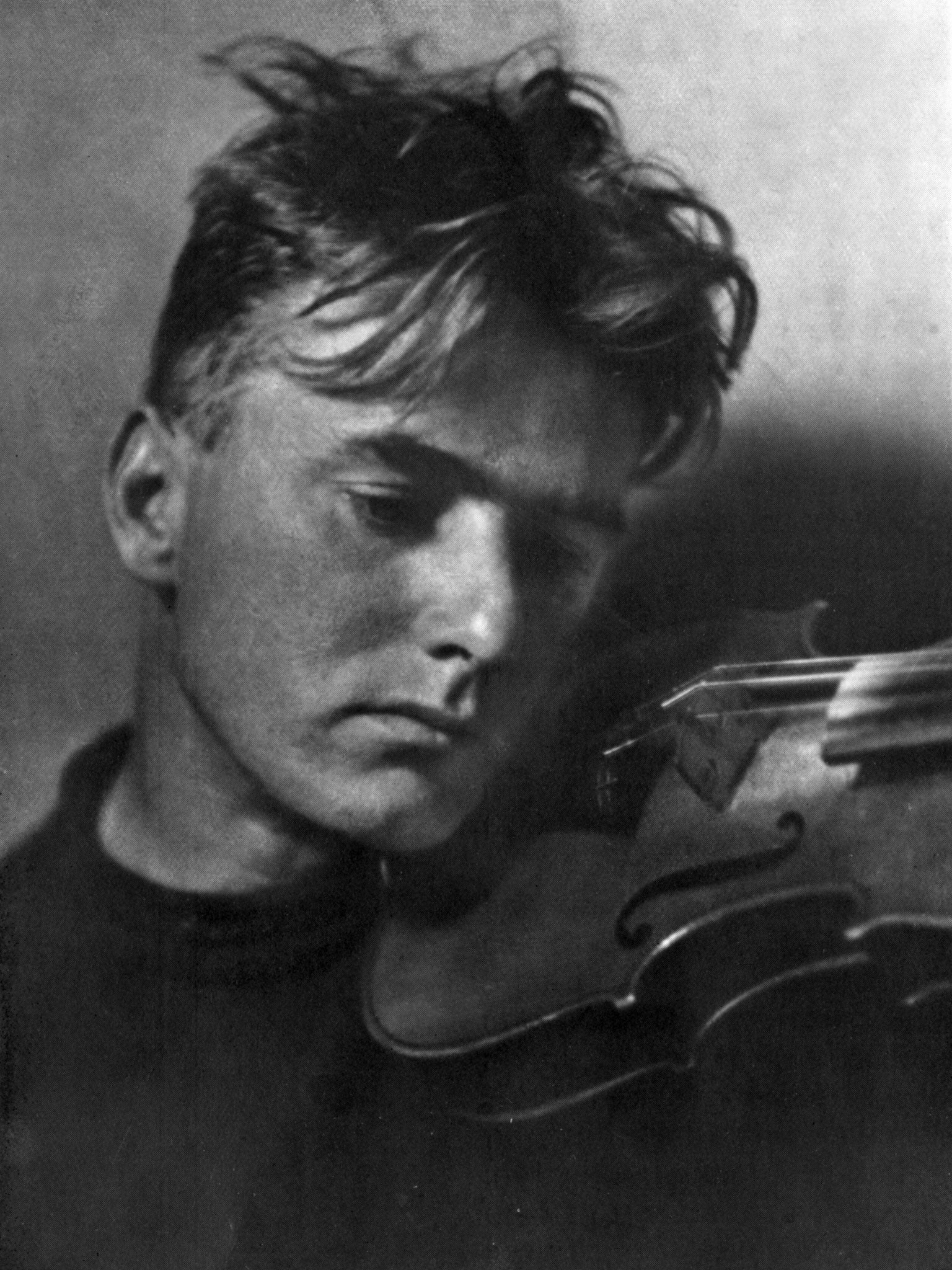

The intimate connection between all of these luminaries: each had their portrait taken by Helen Muspratt, a little-known but extremely impressive photographer who, along with her artistic partner, ran a studio in Cambridge and spent much of her time shooting the town's most famous alumni.

Whether capturing them pensive in posed portraits, playful out punting on the Cam, or sporty in their rowing shirts, the images evoke their book-lined world, but they also pay tribute to Muspratt, a rare example of a working mother, her family's main breadwinner, who was also responsible for some extraordinary and experimental photography. As a woman and as an artist, she was way ahead of her time.

Muspratt (1907-2001) was born and raised in India, the child of a family of high-ranking civil servants, and it was the experience of living so far from "home" that awakened in her an interest in photography, believes her daughter Jessica Sutcliffe, whose book about her mother is out this month. "Because the family was separated, with some of them in England and some in India, photographs were extremely important," she says. "Images were taken and sent back and forth between the family in England and my grandparents and their children in India; they were crucial in keeping k everyone in touch. It gave Helen an early awareness of what photography could mean to people."

Back in England, the young Muspratt was much influenced by a friend of her parents, Francis Newbery, who had been head of the Glasgow School of Art. He encouraged her to study photography, which she did at the Regent Street Polytechnic in London. Her first job was as a photographer's receptionist, but her mother, who had found life as a Raj wife uninspiring, had always encouraged her to take her career seriously, and before long she had opened her own studio in Swanage on the Dorset coast, specialising in snapping holidaymakers.

In 1932, Newbery introduced her to a young widow named Lettice Ramsey, whose gifted mathematician husband, Frank Ramsey, had died two years previously. It was one of the most important meetings of her life. "Helen and Lettice clicked, right from the start," says Sutcliffe. The pair decided to set up in business together and to open a studio in Ramsey's home town of Cambridge, where Ramsey was plugged into academic and social circles.

Muspratt divided her time between Cambridge and Swanage, where her studio continued to flourish. Together, the two women became fascinated by the groundbreaking work of many new exponents of photography, among them the surrealist Man Ray, who was experimenting with a technique called solarisation (which reverses the tone of the dark and light on a negative, making the dark areas appear light and vice versa). They were interested, too, in techniques such as double and triple exposures.

"At the time, this sort of work was cutting-edge," says Katy Norris, curator of a new show of Muspratt's work opening next week. "One series where solarisation worked incredibly well were her images of the mime artist Hilda Spencer Watson and her daughter Mary. The way Muspratt used solarisation techniques suited them perfectly: it was an exotic style of theatre, and this was an exotic way of portraying it."

There were opportunities for documentary photography, too: in 1935, Muspratt, a committed communist, travelled to Russia, and was very taken with the more egalitarian way of life, particularly the availability of crèches for working mothers. Later, she visited south Wales, and took some remarkable pictures of miners and their families. "These documentary photographs are extremely moving," says Sutcliffe. "They show her skills as a photojournalist; although that's not the career she followed, she had a talent for it."

In the other major partnership of her life, with her husband, Jack Dunman, Muspratt was pioneering in another way. Dunman, a fellow communist, wanted to devote his life to the party, and they took the decision that she would be the family breadwinner. Three children followed, including Sutcliffe, and Muspratt and Ramsey expanded their business with a new studio in Oxford. But, says Sutcliffe, though the arrangement was ground-breaking in its time, it was certainly not egalitarian when it came to family life. "Jack was very much the absent father," she says. "My mother was running the family, looking after us children, at the same time as being the earner. It was quite a struggle, and very hard work."

As businesswomen and as mothers, Muspratt and Ramsey understood the needs of working parenthood in a way that not many people did at the time: they gave one another space, and breaks, and were pioneers of what so many working parents have to do today, juggling the needs of their children with the needs of their work.

As professional partners, they were also unusually lacking in ego: many of their photographs now held in the National Portrait Gallery – and there are plenty of them – are neither clearly Muspratt or Ramsey, because they didn't think ownership or differentiation was important.

One casualty of being the breadwinner, though, was Muspratt's experimental photography: she was forced to make commercial decisions because of the need to provide for a family. If she had been the wife of an earning academic, she would quite probably have had the time to continue her more artistic photography. As it was, conventional portraits became her mainstay. They, though, are remarkable in their clarity, honesty and intimacy. "She was always fascinated by the shape and angle of people's faces; she used to say she was never in any situation where she wasn't thinking about how to photograph the people she was with," says Sutcliffe.

Muspratt lived out her later years in West Yorkshire, surviving long enough to see her work acknowledged by a Channel 4 programme and an exhibition at the Bradford Museum of Film and Photography, part of a project to reassess the work of 20th-century female photographers.

Though she and Ramsey uncoupled themselves as business partners soon after the war, they remained close. "Until the end of Lettice's life in 1985, they would meet up at least once a month. They would talk about photography, show one another their latest work, and discuss techniques," Sutcliffe remembers. "It's wonderful that their work – because this show is really about Lettice as well – is having a moment now, after their deaths and after lives of comparative obscurity."

'Face: Shape and Angle – Helen Muspratt Photographer' by Jessica Sutcliffe is published by Manchester University Press, priced £25; an exhibition of Muspratt's work is at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, until 8 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments