Grayson Perry on popularity, pottery and class: ‘I still enjoy looking for discomfort in the faces of the overeducated’

The Turner Prize-winning artist talks to Mark Hudson about why art shouldn’t feel like homework, why he used to have a ‘screwed up’ relationship with art dealers, and his new retrospective ‘Smash Hits’

Grayson Perry has just hung the biggest exhibition of his career, and it’s brought on an epiphany. “I’ve come to realise I’m a very old-fashioned artist,” says the irrepressible Turner Prize-winning potter, relaxing in his London studio. His concerns, he tells me, were “do the colours go together, are the compositions working, is it a nice texture” – basically, “what looks good together”.

That might seem a surprising pronouncement from someone who is widely regarded as having changed our perceptions of what an artist can be. Since coming virtually from nowhere to win the 2003 Turner Prize – notoriously wearing a dress to accept Britain’s biggest art award – Perry has been hyper-visible across an extraordinary range of platforms. He’s traversed Britain in TV series challenging our ideas about art and taste. He’s published books detailing his harrowing childhood and redemption through therapy. He’s done stand-up comedy, newspaper columns, and a new musical about his life, for which he’s written the lyrics. Oh, and back in June he was knighted by Prince William, with Perry again, of course, wearing a dress and full make-up.

Yet it’s clear talking to him that – unlike, say, Andy Warhol or Tracey Emin – he doesn’t regard everything he does as art. “Those other activities are just me having a go at things. I take them on without any prior skill. I’ve learnt on the job with everything I’ve done, including pottery. And I really enjoy doing all these things, but I don’t consider them part of my visual art.”

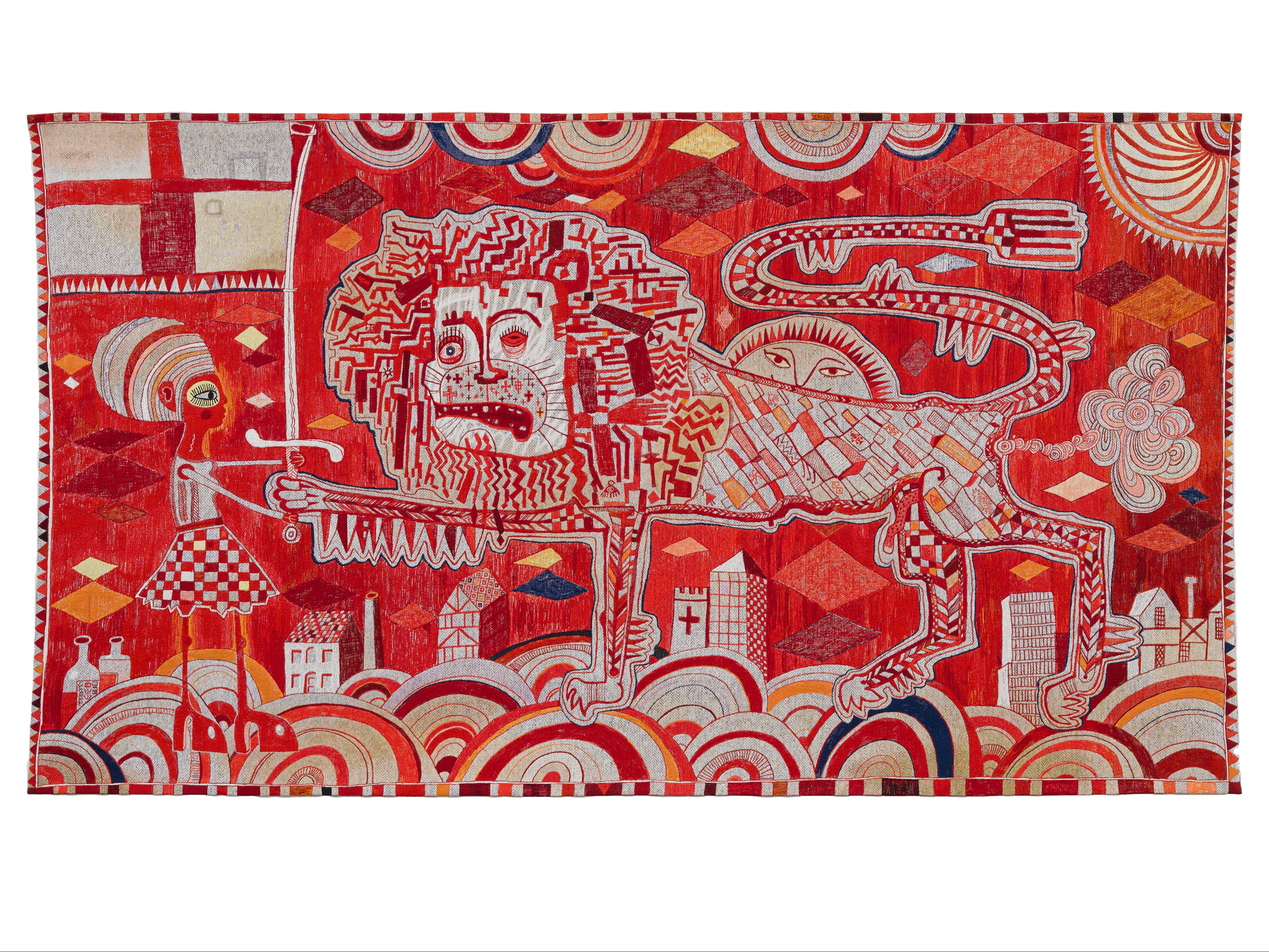

And those “other activities” haven’t prevented him from making the work to fill Edinburgh’s vast National Galleries of Scotland (Royal Scottish Academy) for his new career-spanning show. Wryly titled Smash Hits, the retrospective covers the full gamut of 40 years of his work, from the quirky pots that made his name to picture maps of British class and neon-frenetic tapestries inspired by Hogarth. “It’s just the most colourful exhibition,” he says with delight. That focus on how it looks – what looks good together – is clearly one he’s relished. It’s a consideration that he believes “a lot of artists today forget”.

“There’s a lot of emphasis on issues.” He says the word almost with distaste. “People forget that it’s got to look nice, that we go to galleries for fun. We go to galleries on our days off. We don’t go to get homework.”

Yet Perry has hardly harmed his career by dealing with issues, including identity, gender, class, taste and religion, to name just a few of those listed in his show’s catalogue.

“That’s true. But there’s a lot of art around today that has the dour veneer of seriousness, but is actually just a bit s***,” he says bluntly.

Success hasn’t dented Perry’s readiness to take a swing at whatever gets his goat. And at a time when even modestly successful artists surround themselves with protective networks of dealers, assistants and studio managers, Perry – arguably Britain’s most famous and popular artist – seems startlingly open and available. He answers the door to his studio himself, makes the coffee – “It’s instant, is that OK?” – and within moments we’re chatting away as though we’ve known each other for years. The studio is a surprisingly small, garage-like space, and Perry’s manner of dress is by his standards modest: pink T-shirt and brilliantly coloured dungarees. (The pattern proves on close inspection to depict female genitalia rather than flowers as I initially thought, but what do you expect?)

“There’s a lot of art around that feels like student work,” he says. “Like it hasn’t occurred to the artist that anyone else might have thought that climate change is a bad thing.”

With cancel culture making us all ever more desperate not to offend, Perry’s frankness is refreshing, whether he’s dismissing “upper middle intellectuals who are dead from the neck downwards” or young climate-conscious artists who are already “behind the times, mate”.

But his Edinburgh show, which opened on 22 July, is clearly the thing most on his mind today. “What I’d really like to do,” he says in a tone almost of wonder, “is to go round it with someone who doesn’t know me or my work, but is receptive to art. Just to see what they make of it.”

Which takes me back to my first sighting of Perry’s work at the 2003 Turner Prize exhibition. He was the outsider among the four contenders, with the Chapman Brothers firm favourites, and completely unknown to me. But peering at the ornate surface of one of his mock-grandiose vases, I caught sight of a sulky teenage girl’s face with the words, “F*** off you middle-class tourist”. I was instantly a fan. Perry lets out a ringing, almost satanic cackle at this recollection – a classic Perry laugh, and one of numerous that punctuate our conversation. “I’m glad you had that experience. That’s exactly the reaction I would like.”

Anyone who gets at all popular in Britain has to be aware that there are plenty of people who will relish seeing them fall

His work’s mixture of self-mocking craftsmanship – he denies to this day that he’s a good potter – and edgy humour clearly spoke to many. Within 48 hours of my first sighting of his work, Perry had accepted Britain’s best-known art prize as his female alter ego Claire, with the classic headline-grabbing utterance “What the art world needs is a transvestite potter” – and had instantly become a national figure. Over the subsequent 20 years, he’s made himself so ubiquitous across so many areas of British life that I feel I can hardly get to the thing that is supposedly his raison d’etre: his art.

“Yeah, all those things do affect my art, I’m sure. I’m well organised. I make sure there’s plenty of time for the work I need to produce. But popularity is something I’ve flirted with for years, precisely because it’s so frowned upon by the po-faced contemporary art establishment. And I’m talking about genuine popularity rather than, ‘Oh look, here’s a theme park ride we can all go on!’”

Theme park rides? Who could he mean?

“I remember watching people going on Carsten Holler’s slides” – the German artist’s stainless steel slides exhibited at Tate Modern to great excitement in 2006 – “and thinking, ‘They’re enjoying that, but do they think it’s good art?’”

Perry clearly thought it wasn’t. But does he now feel genuinely popular himself?

“Yeah,” he shrugs, with a “why wouldn’t I” nonchalance. And despite two decades of hyper-visibility, he has never faced a backlash. The idea that a transvestite is best placed to lecture British men on masculinity and the need to show vulnerability hasn’t become annoying. There have been grumbles from snooty critics – who, me? – but neither the British public, nor the media, nor the so-called art world have quite got fed up with Grayson Perry.

“Well, we’ll see,” he says. “I’ve been waiting 20 years for it to happen. Anyone who gets at all popular in Britain has to be aware that there are plenty of people who will relish seeing them fall.”

Perry is such an adept interviewee that it’s hard to get past the practised blokey affability and even start to get a rise out of him. He effortlessly shrugs off suggestions that would seriously annoy most other artists: that he is essentially a product of the British love for a “character” (“Of course, but it’s not an act”); that he’s the David Hockney of his generation (“Totally”). Perry only really raises his eyebrows when I suggest that he doesn’t just love the work of so-called “outsider artists” – now officially known as “self-taught artists” – he actually is an outsider artist himself.

Perry has made known his enthusiasm for, and debt to, marginal artists with startling personality particularities, such as Henry Darger – a great favourite of Perry’s. Darger was an American janitor who left behind a 5,000-page autobiography and hundreds of drawings depicting horrific battles between armies of baby girls. While “normal” artists have been taking inspiration from such figures at least since the interwar heyday of the Surrealists, and Perry clearly regards his own interest as falling within that tradition, he has far more in common with artists like Darger than he might like to admit.

Much of Perry’s work has little to do with the contemporary art mainstream. The conceptual framing that is such a feature of most contemporary art these days barely figures in his. His troubled family background (Perry fled his bullying stepfather, but was turfed out by his real father when he was found aged 15 putting on women’s clothes) isn’t an affectation. Works like his pink motorbike with a shrine to his childhood teddy Alan Measles on the back are presented as jokes on himself, but are actually much more genuine and “sincere” than we might assume.

“I make things that require a fair bit of skill, if that’s what you mean. They take a long time to make. They’re special! I don’t want to walk into a gallery and see any old bit of junk that’s been dragged in and anointed with the magic fairy dust of contemporary art in a way that goes back to Marcel Duchamp [who famously turned a urinal into a work of art in 1917]. That fairy dust is now worn out. It’s been done.”

Maybe the key to Perry’s popularity, far more than the jovial transvestism, is the fact that the ordinary gallerygoer can imagine themselves making his work in a way they certainly couldn’t with a piece of hardcore conceptualism. “Yeah, I think that’s why Grayson’s Art Club (his lockdown TV show in which he gave art classes) was so successful. People saw me working alongside them in a way they could understand. I’ve loved the fact that people have come up to me since my Edinburgh show opened and said they were inspired by it to make their own art.”

I was a very angry, messed-up 20-year-old, and I think I projected a lot of difficult parental stuff onto dealers

Yet at the same time I’m struck, talking to Perry, and reading his essay in the exhibition catalogue, by how frequently he uses that vexed term “the art world”. Where I’ve always understood it to mean the commercial art world, with its dealers, curators, collectors and hangers-on, rather than actual art or artists, for Perry it seems a catch-all for everything that art is. And while he’s made it his mission to call this milieu to account for its pretentiousness and elitism, he expresses anxiety again and again that he was “nervous of [his] position in the art world” or “lacked confidence” in it. Why, if he’s such a free spirit, did he even care?

“It’s a dance!” he says, in a tone almost of exasperation. “I was ambitious! The young person who wants to rebel is inevitably embraced by the art world. The 20th century was a succession of challenges to the art establishment. And by the time I came along, I felt we were running out of angles. I chose pottery because it was beyond the pale somehow, it had the taint of craft. Right up to when I won the Turner Prize, the powers that be were pushing back with, ‘Oh, they’re just pots.’”

Yet Perry’s approach to the art world seems to betray an almost childlike sense of need. Maybe after his troubled childhood, he was looking to the art world as a kind of surrogate family.

Perry concedes this could be true. “I used to have a very screwed-up relationship with the dealers who were trying to sell my work – before I had therapy. I was a very angry, messed-up 20-year-old, and I think I projected a lot of difficult parental stuff onto dealers.”

And that relationship seems to have had a strong element of the Oedipal. “It could be. You don’t get into the culture business without a desperate need for validation.”

Oedipus, of course, slept with his mother, then killed his father – or maybe the other way round. This elicits the biggest guffaw yet from Perry. But maybe, I suggest, his urge to destroy the art world has subsided a bit.

“I don’t think I’m alone in that. Maybe I’m more self-conscious around that world now. But I still enjoy looking for discomfort in the faces of the overeducated,” he chuckles. “If there’s one category of people who continually get in my crosshairs, it’s the upper middle classes – the Hampstead intellectual, book-lined study kind of person.”

I tell him his concept of intellectuals feels a touch dated. Nowadays intellectuals would be lucky to get a flat in Walthamstow, never mind a house in Hampstead. When he refers to the upper middle classes, he’s surely talking about what used to be called the intelligentsia.

“I’m talking about the intelligentsia, and they of course are my world. Most of my friends are in that category, and probably me too. That’s why I love teasing them.”

Indeed, as he admits in his catalogue essay, as Sir Grayson Perry he is now very much part of the establishment.

“God, yes. There’s nothing worse than the threadbare Mohican of the person who’s still banging on about being a rebel when they’re in the upper echelons of the culture establishment. And nowadays that’s an interesting place to be. You have a certain amount of power, and you can play with that.

“No,” he says with a sigh, “I can’t pretend to be a rebel any more.”

‘Smash Hits’ is at the National Galleries of Scotland (Royal Scottish Academy) until 12 November

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks