Freud and Eros: Love, Lust and Longing at the Freud Museum

This exhibition sheds intriguing new light on the psychoanalyst’s own collection of curios and his theories of female sexuality and love

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Last week, I read for the first time from my next novel, which is about a romance writer who gets locked in a mental asylum for pushing against the bounds of the genre. The event took place at Waterstones Hampstead; it celebrated the end of the year-long #ReadWomen2014 campaign, which has aimed to promote female writers, alive and dead. What was striking about it was how all of us – Deborah Levy, Juliet Jacques, Rachel Genn, and Joanna Walsh, who ran the campaign – read work that referred in some way to Freud’s theories. This was a coincidence.

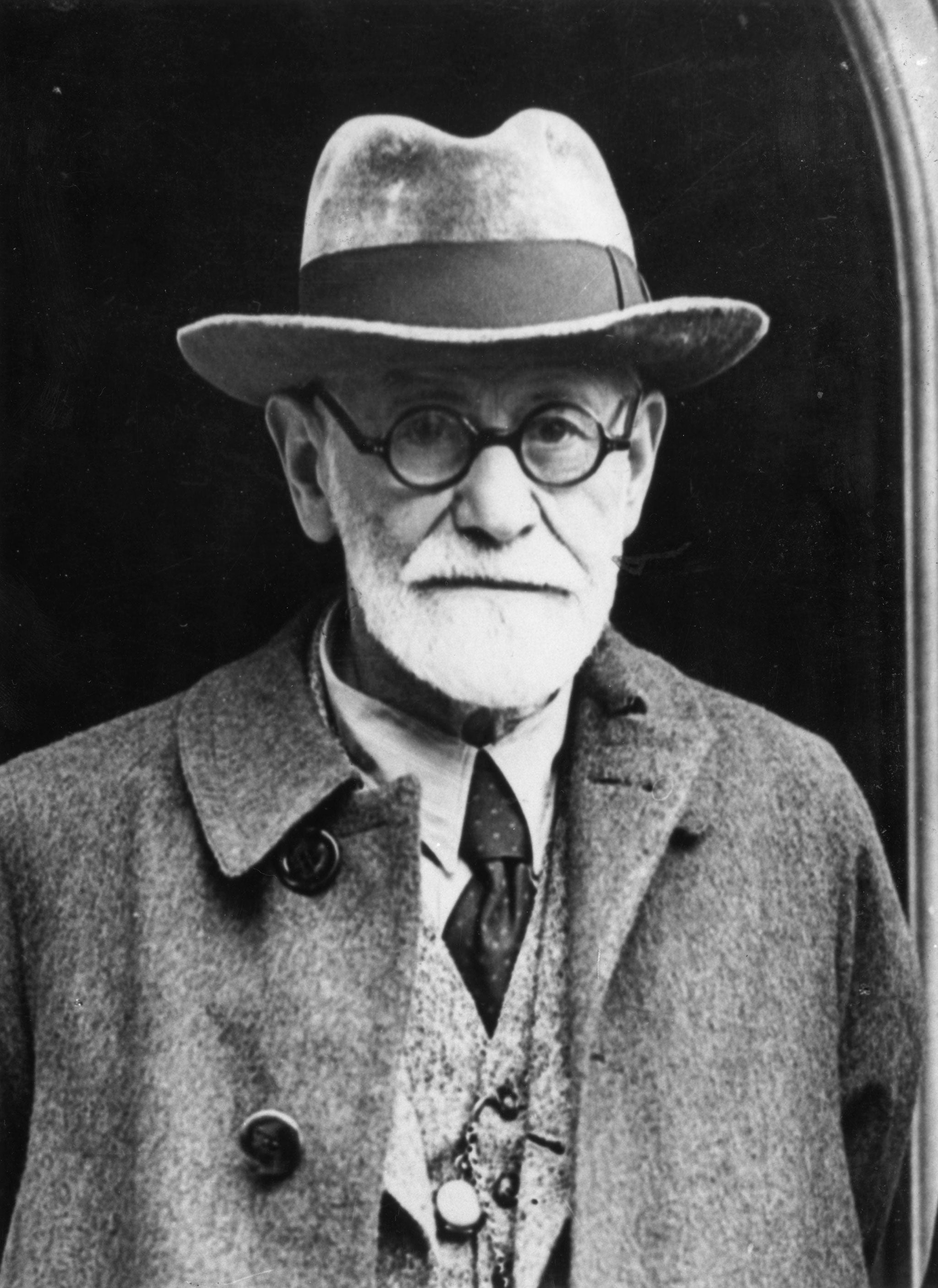

As feminist writers, it seems that we are still arguing with the old Viennese founder of psychoanalysis, who died in 1939. Despite the many patriarchal and frankly absurd aspects of Freud’s thought, he has given much to feminism: the theoretical tools to understand how oppression works – not merely in the exterior world, but in the unconscious, too. As Deborah said, Freud listened to women. Even this simple act seemed revolutionary at the beginning of the 20th century when he was writing.

An exhibition, Freud and Eros: Love, Lust, and Longing, is currently running at the Freud Museum, which is located just around the corner from the bookshop, at 20 Maresfield Gardens, a quiet residential street. It is the house where Freud spent the last year of his life, following his exile from the Nazis in 1938. His daughter, the child psychologist Anna Freud, continued to live there until her death in 1982.

The museum is remarkable: the study is preserved exactly as he left it, with the famous couch, replete with green velvet cushions, on which his patients confessed their dreams, phobias and fantasies. I was lucky enough to be in the museum alone, which was eerie. It seemed as though Freud could turn up any moment.

For several years, the museum has been inviting artists to respond to this sumptuous and strange environment by positioning their own artworks among Freud’s many curios. It’s a great way to bring new life to a permanent collection.

I enjoyed this exhibition a lot. It is small, elegant, and understated, carefully curated by Dr Janine Burke, who has invited contemporary artists to contribute works that respond to the theme of love and lust in Freud’s work. Influenced by the ancient figure of Eros, the “love-force”, who emerged after chaos at the beginning of the world, Freud’s views on love were miscellaneous. He wrote in 1921: “Language has carried out a completely justifiable piece of unification by creating the word ‘love’ with its many uses.”

One of his most interesting ideas is that love and hate can co-exist as “ambivalence”; that the life drive, Eros, competes with the death drive, Thanatos; in other words, human beings are not merely driven towards self-preservation and happiness, but self-destruction too. This often seems to be the case in matters of love.

In 1926, Freud wrote, “[Eros] strives to make the ego and the loved object one, abolish all spatial barriers between them.” This sense of collapsed boundaries is present in Rachel Kneebone’s triptych of white porcelain sculptures, Emerging Out of an Inconceivable Void into the Play of Beings (2014), which is displayed in the hallway alongside Freud’s overcoat and glasses. It is a fascinating and delicate work.

Each sculpture consists of a mound of dismembered legs, vines, and vaginal petals, erupting out of a cracked base. Kneebone is influenced by Ovid’s Metamorphoses; there is a sense of beings changing into other beings, the individual lost in a mass orgy, albeit made up of headless bodies.

Inside the study, a white minimalist sculpture by Edmund de Waal sits inconspicuously among Freud’s collection of 2,000 antiquities, as well as the 1,600 books that he managed to transport from Vienna. And Speech (2013) consists of tubular porcelain pots grouped together in two glass vitrines, which stand close together on a reflective wooden table, but don’t touch. The work has a coolness and stillness that is refreshing among all Freud’s decadent clutter.

De Waal writes that his work is about “wanting, having, and losing”. The sculpture represents a conversation between lovers; the pots are words, the space around them as meaningful as the pots themselves. As De Waal points out, Freud too liked vitrines, in which he stored his antiquities. While working on The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), he wrote that he was aided by these “old and grubby gods”.

Many of Freud’s antiquities related to love and lust are displayed upstairs. They point to his own obsessional tendencies, most notably the 17 different types of ancient phallus amulets. These penis-shaped talismans offered good fortune and asserted male power. In light of Freud’s more outrageous claims about femininity, including the idea that all women suffer from penis envy, the phalluses are not surprising. They appear to be almost a parody of the kind of thing you would expect Freud to own.

One in particular that stands out is a bronze amulet from the Roman era with a “man-bull” face, bull’s horns, as well two phalluses and testicles. It is ridiculously OTT. Also included are Freud’s collection of figurines of Venus, goddess of love and sex. One stands naked from the waist up, admiring her long hair in a hand-mirror. She was given to Freud by Princess Marie Bonaparte, who became his patient in 1925. Freud believed that penis envy contributes to women’s vanity because “[women] are bound to value their charms more highly as a late compensation for their original sexual inferiority”.

According to the gallery text, “his construction of femininity was both problematic and phallic”. To say the least. It is a credit to Burke and the museum that they are not afraid to include some critique of Freud, whose views seem so archaic yet contributed to the process of sexual liberation that took place in the 20th century.

One of the more unusual objects is a stone Baubo figurine from Ancient Egypt. It consists of a naked woman with large breasts, legs splayed, pointing to her vagina. This demonstration of female sexual assertiveness is ambivalent: she may be liberated from feminine modesty or simply intended as an example of vulgarity. In Greek mythology, Baubo was a comical and lascivious figure. Her open sexuality is counterbalanced by her tiny size, which means you have to look closely to see what she is doing; this operates as a kind of concealment.

The catalogue includes a lyrical essay by the former director of the museum, Michael Molnar. He writes that Freud believed “all moods and emotions, pleasant or unpleasant, should be submitted to study”. In this way, Freud’s long courtship and correspondence with Martha Bernays, who would become his wife in 1886, seems to be a prototype for his own investigations into love. Some of their letters are included here.

Freud’s vulnerability, or at least his declaration of vulnerability, is touching. He wrote to Martha in 1882: “When you return, darling girl, I shall have conquered the shyness and awkwardness which have hitherto inhibited me in your presence.” And yet he also wrote: “It seems a completely unrealistic notion to send women into the struggle for existence in the same way as men. Am I to think of my delicate sweet girl as a competitor? ….No, in that respect I adhere to the old ways.”

It is the tension in Freud’s work between the “old ways” of patriarchy and the dazzlingly new ways of understanding the human psyche that he developed that makes this exhibition so intriguing.

Freud and Eros: Love, Lust and Longing, Freud Museum, London NW3 (020 7435 2002) to 8 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments