Piss on pity: How a new archive captures the radical spirit of the Disability Arts Movement

The Disability Arts Movement led to social inclusion and political change in the UK – so why don’t more people know about it?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ever heard of the “social model” of disability? It’s the idea that disability is actually caused by the way society is organised, rather than a person’s impairment or condition – and so it’s this that has to change.

This inspiring theory sits right at the heart of an arts movement that first bloomed towards the end of the 1970s, and led to major advancements in Britain, such as increased accessibility on public transport and the passing of the 1995 Disability Discrimination Act.

Yet strangely, the UK’s Disability Arts Movement isn’t something that’s widely spoken about – except among the disabled creative community. Even as the parent of a four-year-old autistic son, I’m ashamed to say I hadn’t really heard of it until I started working with the team behind the National Disability Arts Collection and Archive, or NDACA as it’s known.

Although a highly successful protest group, the Disability Arts Movement is also inspiring because it brought together a wealth of people from Britain’s creative communities – from comedians and film directors to sculptors and artists. Set up to raise awareness, provoke social discussion and dispel the myth that disabled people want or need to be pitied, it was quite simply ahead of its time.

And with the launch of the million-pound archive later this year – and its digital arm this month – this radical protest movement is now taking its place in the spotlight. The initial plan was to include a thousand pieces in the archive, but cheeringly it has mushroomed to more than 3,500, with more to come; the archive, which is funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, Arts Council England and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, will continue to be added to.

“The Disability Arts Movement broke the struggle for social equality down to peoples’ stories and that’s what I’ve always been interested in – how individuals can change society,” says David Hevey, film producer and director and project director of NDACA. “This project is all about harnessing the power of art to achieve social change.

“The stereotype of disabled people used to be that they were a group who needed our pity, when actually in my opinion it’s always outsiders in society who are the agents of change,” he adds. “You can’t necessarily play football with a disability but anyone can be creative. Art allows people in.”

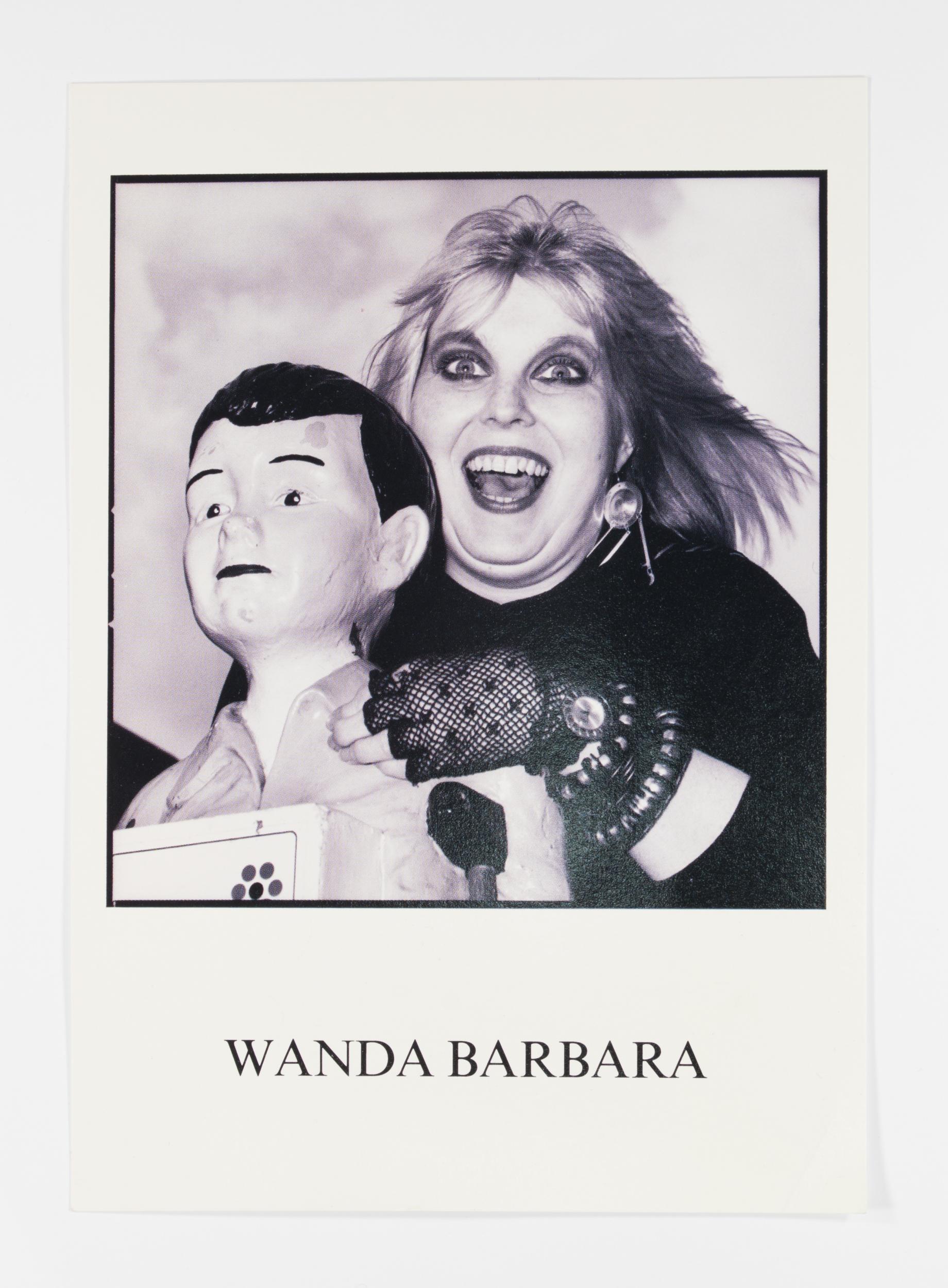

Barbara Lisicki was the first disabled female stand-up comedy artist in the UK, taking to the stage in 1988 at a roving London cabaret night called Workhouse. She was right at the heart of the Disability Arts Movement, and has continued to be involved with disability arts ever since, as well as working as an equality trainer.

She co-founded the Tragic But Brave show with musicians Ian Stanton and Johnny Crescendo in the late Eighties and toured for more than five years across the UK, Europe and America. Johnny’s song “Choices and Rights” later became the unofficial anthem of the disability protest movement.

“My comedy was always satirical and political rather than being about me – just all those stupidities and absurdities you encounter daily as a disabled person. I tried to take the stigma out of it all,” Lisicki recalls.

“A big issue fuelling the protest arm of the Disability Arts Movement was how charities in the 1980s and 1990s portrayed us. The only stories you’d see, were ‘tragic, but brave’ ones – hence the name of our show.”

Advertising billboards would display “the most offensive images”, but that simply did not reflect the reality of the disabled community, Lisicki says.

“We wanted to fight back against these and to counter stereotypes you’d see in films in which disabled characters were either stupid or evil. Even movies like Born on the Fourth of July and Scent of a Woman were troubling, because you had non-disabled actors like Al Pacino and Tom Cruise playing parts that then became almost a caricature.”

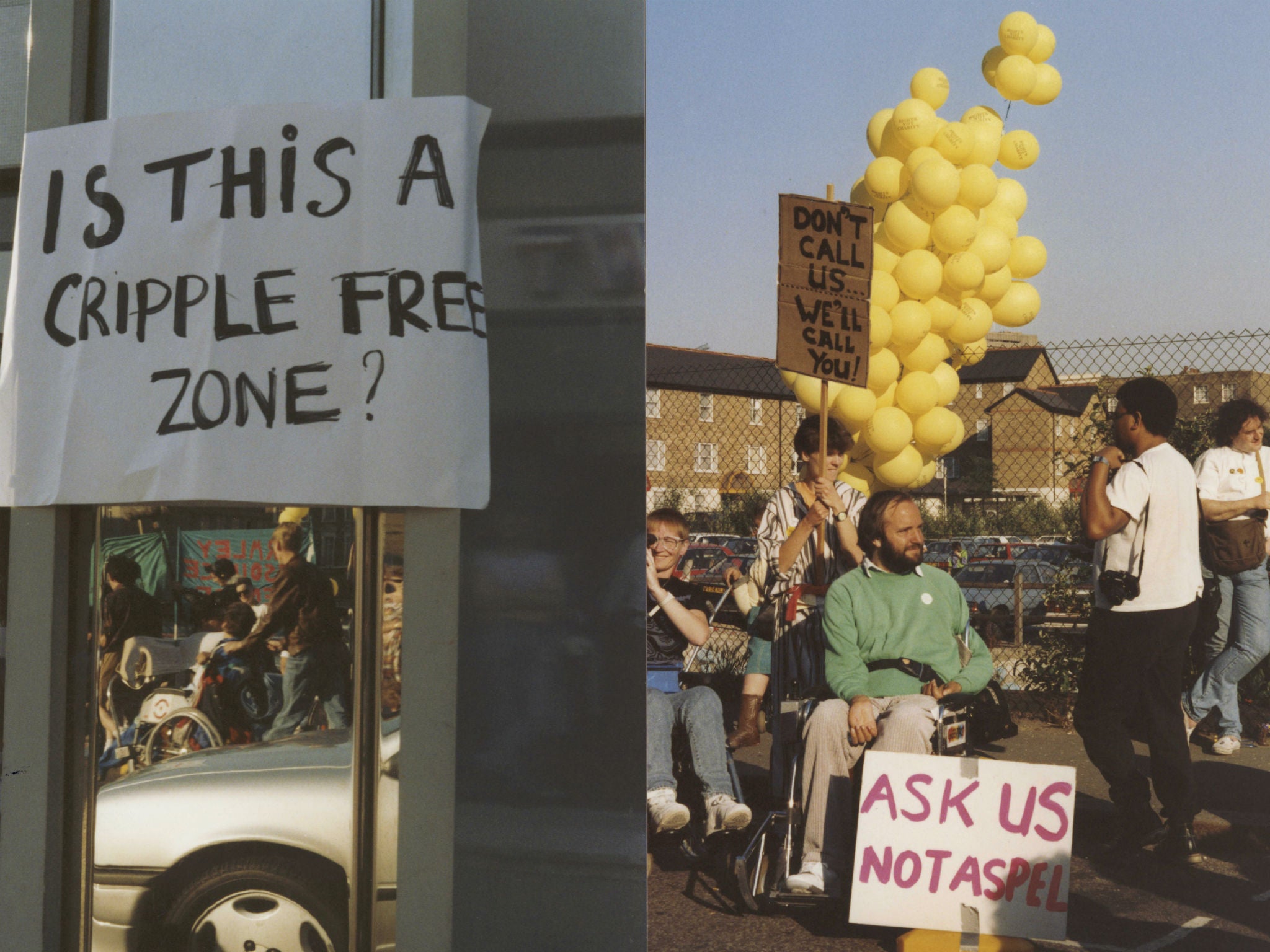

Among the most famous demonstrations that the Disability Arts Movement were involved in were the Block Telethon protests of 1990 and 1992 which took place outside ITV Studios as a stand against these celebrity-studded TV fundraisers.

“These were hideous TV telethons that lasted something like 27 hours and portrayed disabled people in a manner where they should be pitied. It wasn’t representative of the disabled community and was patronising,” she says.

The 1990 protest was organised at short notice, but still managed to attract a lot of media coverage. Two years later, the activists upped their game.

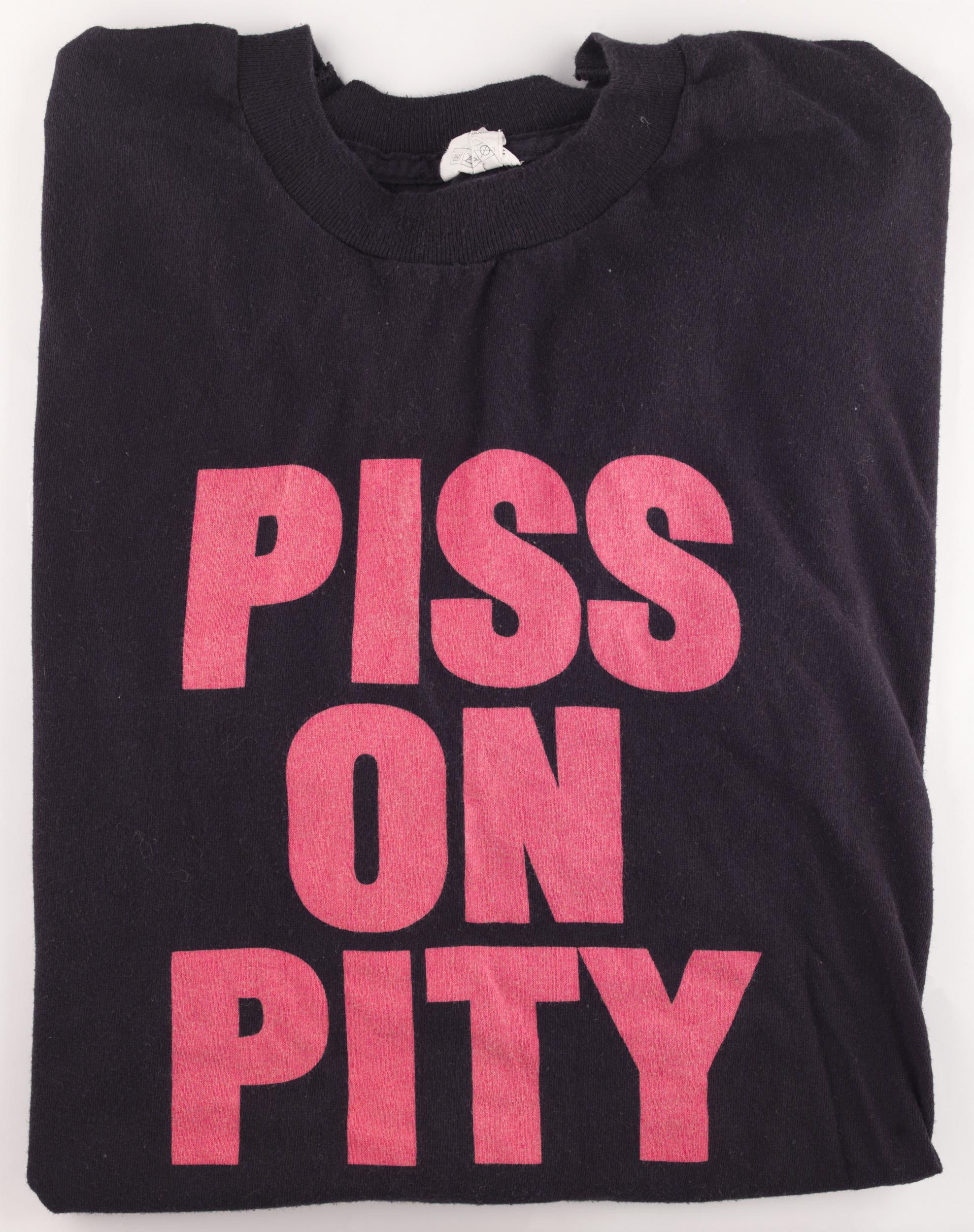

“We took six months to organise the 1992 protest – and that’s where the famous ‘Piss on Pity’ slogan came from,” recalls Lisicki. “The Disability Arts Movement was profoundly political and was there to get people talking. It was completely radical at the time and unique.”

She’s thrilled that NDACA will not only reflect this, but also showcase “all the amazing work across all genres that the movement inspired”.

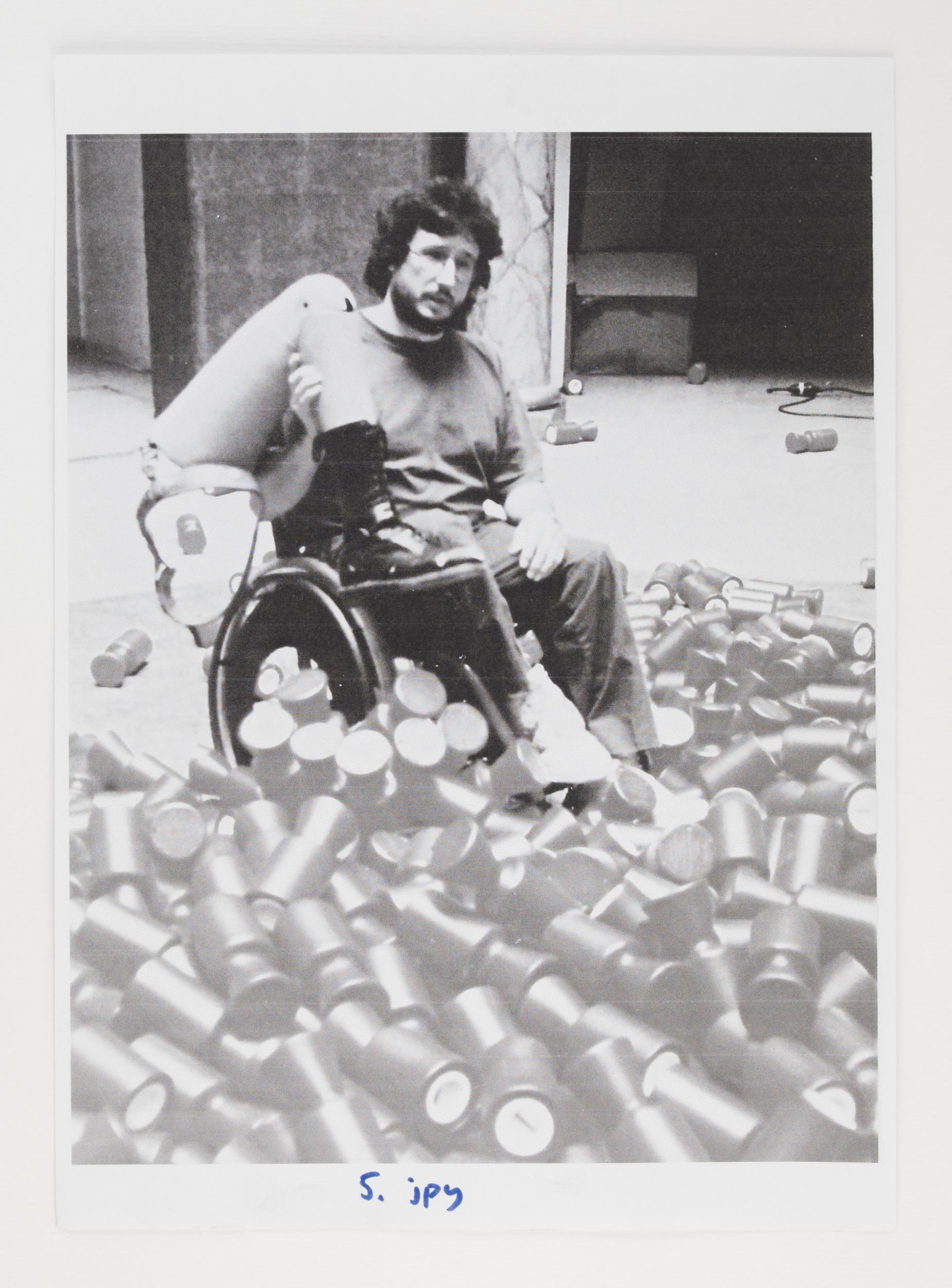

Disabled sculptor Tony Heaton has been central to the archive since its very conception and has worked within the field since the late 1970s. In 1994 he became known for his sculpture Great Britain From A Wheelchair, a map of the nation made from the parts of two NHS wheelchairs, but he’s now perhaps best known for his work on the 2012 Paralympics: his piece Monument to the Unintended Performer celebrated those who took part, and was erected outside Channel 4 studios.

“I first became involved in thinking about an archive some 20 years back,” Heaton says. “The writer Allan Sutherland and I would have rambling phone conversations about how mainstream galleries didn’t seem to be interested in disabled art so we needed to document it.”

Heaton went on to become the first professional director at a facility in Dorset called Holton Lee, and built a gallery and four artist studios there. It is now a wellbeing discovery centre providing respite and rehabilitation to people with spinal cord injuries, but still offers studio space for hire.

“We used to almost exclusively show work by disabled artists and gave them residency, and started collecting pieces,” he remembers. “The work inspired by the Disability Arts Movement was challenging and exciting, but we could never manage to convince curators at the Tate or National Gallery to cover it – despite them championing black art and feminist art. Now, at last, the archive tells “the story of those people, the outsiders.”

While Heaton expresses the hope that people focus on the work rather than the impairments of contributors, he also acknowledges that disability arts can have a powerful educational impact.

“It can enlighten, challenge, and make you remember, and I hope people will visit or log onto the archive and and then go away and think about it – maybe even change their behaviour,” says Heaton.

NDACA’s project manager, Zoe Partington, is an artist herself, with work ranging from photography to digital installations. She says that the very human story of exclusion that the archive charts should resonate with many.

“Disability arts has had a hidden history in Britain,” Partington says. “We want to get the story heard.

“I still think we’re facing discrimination today – it’s just more subtle,” she adds. “People are clever with the language they use but we still have a long way to go. NDACA can help society to become more understanding.”

For project Archivist and Collections Lead Alex Cowan, it has been important the art included “stands on its own merit”: “The quality and range and inventiveness of the art that’s been included in the archive to date is very important.”

But he points out that there’s also an important story of social change to tell here: “It makes stories of struggle recognisable. Many people have been excluded from wider society, but NDACA lays out the story in a nice, clear way.”

And he’s delighted that it will be a “living archive” that will continue to change and evolve: “The plan is to create opportunity for artists as well as provoking discussion.”

But how far do we still have to go to make the arts more accessible in Britain?

“The 1980s and 1990s were a thrilling time in terms of disability activism and saw so much change, but I think over the past couple of decades we’ve lost momentum,” Lisicki laments.

“But I think NDACA will get people talking again. I’m so glad that work we did back then has been captured for future generations. The NDACA means the history of disability arts won’t get lost – it’s a crucial tool to create momentum for disabled people and change.”

The National Disability Arts Collection and Archive launches later this year at Buckinghamshire New University, with the digital launch at the end of June (the-ndaca.org)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments