Time to rise up: the story behind Tate Britain’s feminist artwork made from cake

In 1976, performance artist Bobby Baker invited strangers into her home to feast on an edible family in the name of feminism. Almost half a century later, visitors dreaming of a batter world can tuck in again as it’s restaged outside Tate Britain. Annabel Nugent speaks to the artist ahead of its opening

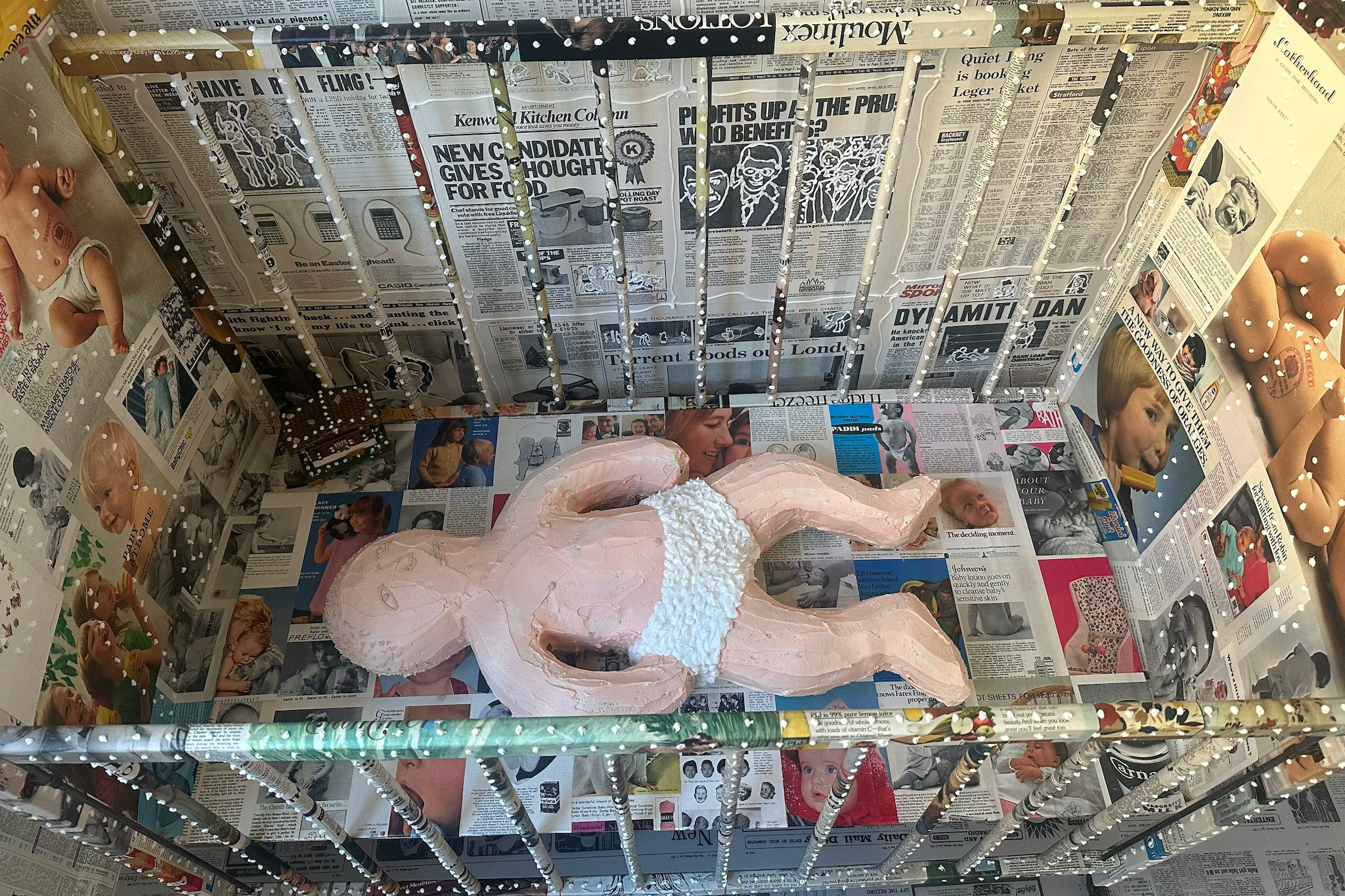

A woman is marvelling at the bright blue frosting above her head. “How do you pipe icing on a ceiling?” she asks. It is one of many fantastical questions I hear while wandering through Bobby Baker’s An Edible Family in a Mobile Home. Almost 50 years after its original installation, Baker’s show-stopping feminist artwork is back – this time on the south lawn outside the Tate Britain. “Who baked Coconut Cake Baby?” is another question I overhear.

The big question, though, is how does a family made of flour, eggs and sugar end up outside of the Tate? Baker was invited to restage her seminal installation as part of the museum’s Women in Revolt! show, which opens this week and offers the first major survey of feminist art in the UK, with Lubaina Himid, Sonia Boyce and Mona Hatoum featuring on a lineup of over 100 artists. Baker’s work, situated outside the museum’s entrance, is the amuse bouche.

Just as when it was first seen in 1976, visitors are welcomed not only to look and touch but to eat her sculptures. coconut cake baby is one of five edible family members who have been faithfully recreated for the installation; there is also a daughter made entirely out of meringue, listening to Donna Summer’s breathy vocals piped out of a vintage radio in the bedroom, and a teenage son constructed from Garibaldi biscuits, bathing in a tub of moist chocolate cake. Presiding over the living room is a fruit cake father sunken in his armchair, while the mother is (of course!) in the kitchen. Built from a dress mannequin with a teapot for a head, she serves up crackers and dried fruit from her hollow abdomen. The house is covered floor-to-ceiling in newspaper pages, magazine clippings and, in the son’s bathroom, comic-book strips all dated to the mid-Seventies.

It took two months for the installation to come together, but Baker’s work is not yet done: today, she plays the polite female host, a role she first embodied in the Seventies. “Milk and sugar?” chirps the artist from the kitchen, wearing an apron and chunky spectacles. This time around, Baker has trained a small troupe of others to share in the hostess duties. Mother, daughter, son, father, baby, Baker; the whole gang’s here – housed in a replica of Baker’s prefabricated home in east London where at 25 years old, she first staged the exhibit. Now 73, the performance artist has had plenty of time to digest its meanings.

Baker has lived up to her surname for nearly three decades now. Over the years, she has grown a reputation for making work that subverts traditional ideas around domesticity. Typically, her art – meringue ladies, breadstick antlers, emotions manifest in black treacle – strives to bestow importance on the undervalued aspects of women’s daily lives. It makes sense then, to interpret Edible Family, with its edible ménage and domicile setting, as part of her wider purpose. Back then, though, Baker says she had other intentions.

“I had studied painting at Central St Martins, and I found myself in an environment that I enjoyed but one in which I was clearly not going to be taken seriously,” she recalls over the phone a few days before Edible Home 2.0 opens. “I found it very elitist and very, very male; you had to sort of pretend to be a man or you weren’t taken seriously. I abandoned that art world and discovered the delight in making work out of food. It felt very subversive and radical and witty to be making bad things out of rather pathetic objects.”

It was around this time that Baker moved into a small estate house in Stepney courtesy of Acme, a charity dedicated to supporting artists in economic need. “Families were being gradually moved off but there were still plenty there and so I was surrounded by people with young children, and I knew immediately that I wanted to make a life-sized family. It just seemed a very obvious thing to do at that stage without too much questioning.”

In its original iteration, Baker did everything on her own. “My impression was that for a work to have integrity, you have to do it all and that’s what I did,” she recalls. “I made the cake, I sculpted the cake, I made the invitations, posted them, and printed them. Everything.” She does confess, however, to asking her friend (and partner at the time), photographer Andrew Whittuck, for help plastering the ceiling with newspaper. “I thought it was cheating, but I needed him because he was so tall!” Her boyfriend’s freezer, which he used to store his camera film, also came in handy when it came to preserving the cake for weeks on end.

Preservation is, however, not the point of Edible Family. Today, as I enter the replica home it’s the smell that hits me first. The air is dense with the scent of spun sugar and whipped butter; it’s delicious – and yet you can’t help but imagine what it will smell like a month from now. “Rancid,” Baker laughs as she recalls the stench of her Stepney home after just one week. “It was utterly beautiful at the beginning and by the end it was macabre, there were crumbs and remains. The whole family was destroyed.”

By the end, it was macabre... the whole family was destroyed

Interestingly, it was only then, seeing the family decimated by hungry mouths, that Baker realised it was, in fact, her own family that she had modelled her work after. “I hadn’t consciously realised that when I was making it,” she says. “I’d had rather tantric sort of experiences when I was young; my father died when I was 15 and we had a very troubled time afterwards. We remained a strong family but I think I was probably reflecting on that.”

Barker had not set out to make any feminist statement with her edible family – that message is something that has emerged with time. “My experience has taught me increasingly that these strange ideas and images can become more clearly understood as you make them in hindsight – and that’s what has happened,” she says. “I’ve subsequently had children and grandchildren and I have become more clearly focused on the notion of unpaid domestic labour. The pandemic really crystallised that it is such an incredibly important part of life; how essential it is to how the world operates, how we look after each other and how we care for our children – and yet it still has words like ‘menial’ attached to it. I think it has a lot to do with class and women and poverty.”

A few things have changed since that first installation (for one thing, pumps of hand sanitizer are duly doled out before entry; the newspaper on the floor is sealed in plastic for a mess-free experience; one of the cakes is vegan-friendly) but mostly, Edible Family remains unchanged, a testament to the lasting, enduring power of great art – even when that art is gobbled up and gone within a few days.

‘Edible Family’ is open to the public at Tate Britain from 8 November – 3 December 2023 and from 8 March – 7 April 2024

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks