Ruin Lust at Tate Britain, art review

The eerie beauty of ruins has seduced artists from Turner to the YBAs, as Zoe Pilger discovers at Tate Britain

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“Walking along the beach some years ago, I noticed a dark structure emerging from the mist ahead of me,” the novelist JG Ballard wrote in 2006. “Three storeys high, and larger than a parish church, it was one of the huge blockhouses that formed Hitler’s Atlantic wall… A flight of steps at its rear led me into the dank interior with its gun platforms and sinister letter box view of the sea. Generations of tramps had dossed here, and in the stairwells were the remains of small fires, piles of ancient excrement and a vague stench of urine.”

This stunning piece of travel writing inspired twin YBAs Jane and Louise Wilson to visit the Atlantic Wall in 2006 and photograph the ruined blockhouses or bunkers, built by the Nazis to defend the coastline from France to Denmark and Norway. Their extraordinary images are some of the most poignant and powerful in a new exhibition at Tate Britain, which explores our lust for ruins (from the German ruinenlust) over the past three centuries.

Why do we lust after that which is past? How can the past somehow exist in the present? This is the conundrum of the ruin, which seduced aristocratic tourists on the Grand Tour of Europe in the 18th century and continues to appear in twitter feeds, captured through the romantic filter of Instagram. The condition of lusting after ruins seems both human and slightly obscene.

Co-curated by the writer and critic Brian Dillon, this exhibition is conceptual without being cold. From Turner to Tacita Dean, across painting, film, and sculpture, it explores the idea of the ruin “of the mind” as well as the real human history that underscores these monumental and often beautiful wrecks. It’s utterly absorbing and educational. I emerged from the gallery and looked at the skyline of London anew – the ruins we live among.

Urville (2006) is a vast black and white photograph by the Wilsons. It shows a hulking Nazi bunker, seemingly toppled on its side. The bunker looks like a broken Transformer toy – cartoonishly brutalist. The walls have been vandalised, as Ballard describes, and there too is the letter-box view of the sea. The bunker is surrounded by sand, and there are footprints leading up to or away from it. The sky overhead seems about to break into a storm. There is a sense of violence, held at a distance. It is a spectacular image – bold and tragic.

There is great sensitivity to the workings of power in this exhibition. Ballard saw a link between Nazi brutalist design and the postwar city planning in Britain that contained and controlled the working classes. This was one of the most radical elements of his thought and fiction. He wrote: “I realised I was exploring a set of concrete tombs whose dark ghosts haunted the brutalist architecture so popular in Britain in the 1950s… sprung from the drawing boards of enlightened planners who would never have to live in or near them.” Dillon pursues this Ballardian theme with subtlety. Several works explore the ghettoization of the poorest in London, and the waste of uninhabited urban spaces. This brings the idea of ruin right up to date.

Estate Map (1999) is a large work of acrylic paint and marker pen on an aluminium background by the artist collective Inventory. It shows a damaged and degraded map of the Marquess Road housing estate in Islington; the letters are eroded and the yellow blocks that signify houses are partly erased. The image is like an abstract painting, and, indeed, this is a living space abstracted out of existence. Across the bottom of the image, the artists have written about the “feeling of absence” created by the fact that such estates are not included on city maps. They are blanks, their inhabitants both symbolically and actually excluded. This is part of “the ideological stranglehold of space which organizes any city”.

It is important that these politically committed works are included. While the idea of the ruin was aligned to the picturesque in the 18th century, referring to charmingly decayed medieval abbeys and classical temples, here the ruin is an issue of urban deprivation. One of the most influential writers on the picturesque was William Gilpin, who described Tintern Abbey in 1782 as “a very enchanting piece of ruin. Nature has now made it her own.” And Denis Diderot wrote in his Salon of 1767: “The ideas ruins evoke in me are grand. Everything comes to nothing, everything perishes, everything passes…” Instead, many of these ruins are about contemporary Britain.

I love Laura Oldfield Ford’s large painting TQ3382: Tweed House, Teviot Street (2012). It is striking because it shows an interior, domestic space rather than the exterior of a building. The domestic is historically feminine, but this is more riot grrrl than girly. Two women sit on an unmade bed, writing. They are ambushed on all sides by florescent pink paint. Oldfield Ford is influenced by punk, squatting, and rave subcultures, and the painting looks as though it were made in the Eighties. The women’s hairstyles are retro. Tweed House is a block of flats next to the Blackwall Tunnel in east London, an area of industrial spaces used by artists. Always precarious, this is a scene of creative life under threat. Artists are being priced out of London.

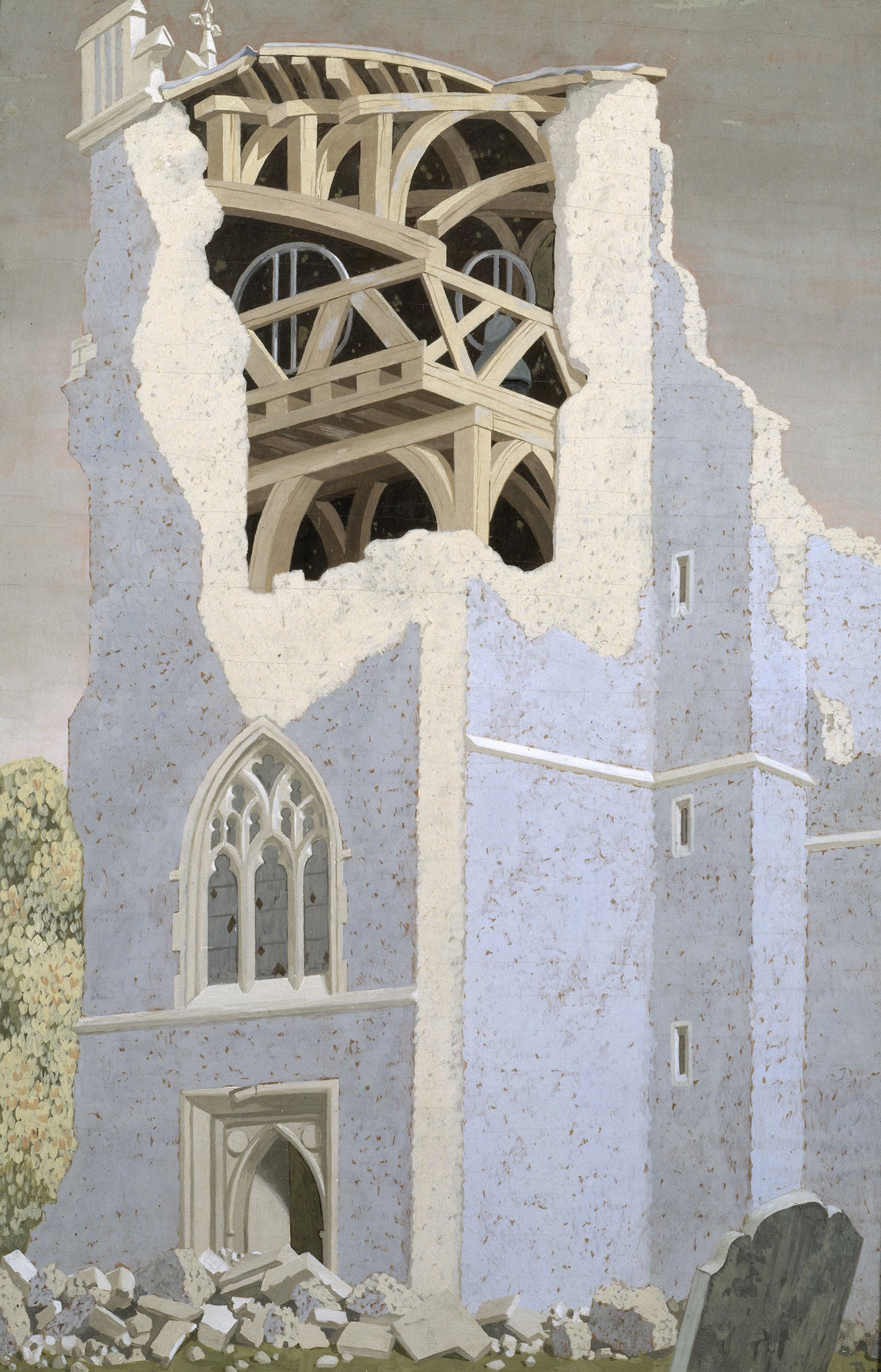

Joseph Michael Gandy’s A Bird’s-Eye View of the Bank of England (1830) appears all the more astonishing in light of the political anger of these works. It is a surreal and timely example of how the British establishment has evoked the idea of ruins in order to cement its own power. The large gold-framed watercolour painting was commissioned by the architect Sir John Soane, who designed the bank, to celebrate his own retirement in 1830. Rather than show the building in pristine condition, Soane asked Gandy to imagine it in a state of decay. The cutaway perspective allows you to see the interior of the building, evoking the ruins of the Colosseum in Rome. By accelerating the ageing process in this way, Soane is aligning his creation with the classical world. It’s absurd.

The painting itself is whimsical, nostalgic, lightly Romantic. The pale sandy palette and shafts of blue light falling from the left are Turneresque. Far from the busyness of central London, the bank is surrounded by an exposed red cliff face and a fallen classical statue. The suggestion is that civilization may fall, but the bank will remain. It belongs to the grace of things past, not present. This is mystification in action. It is an instance of how art has served the elites through the centuries.

This exhibition is astute and critical rather than cosy. It shows in a fascinating way how our understanding of the ruin has changed. Following the mass violence of two world wars, the smoking, nightmarish cities left in their wake, the ruin was no longer an aesthetic ideal, viewed from a distance. It was no longer picturesque, but an immediate reality for those bombed out generations who were forced to rebuild their lives from nothing. To aestheticize such disaster without awareness would be wrong.

It is with great compassion, then, that Graham Sutherland painted the destruction of London during the Blitz. Employed as an official war artist, Sutherland’s gouache, graphite, pastel, and ink on card, Devastation, 1941: East End: Burnt Paper Warehouse (1941) is one of the most affecting works in this exhibition. It is full of pain and energy. Workers watch as the paper warehouse writhes like an animal, torn apart by a bomb. It seems to be spewing mechanical entrails. Paper is a symbol of civilization – here destroyed. In some way, the painting brings to mind the hubris of those Nazi bunkers, “left behind by a race of warrior scientists obsessed with geometry and death”.

Ruin Lust, Tate Britain, London SW1 (020 7887 8888) to 18 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments