British Art Show 8: Computers and cameras dominate and leave painting and sculpture out in the cold

Since its inception, every five years different curators have taken on the challenge of presenting a snapshot of the contemporary art scene

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The British Art Show 8 makes big claims, saying it is now the most ambitious and significant survey of British contemporary art today. Visiting it, then, one should get an overview of the current state of British art. Having been to all three venues spread across Edinburgh, I am pleased to say that artists residing in Britain are producing much to applaud and admire. That praise comes with the caveat that it would be good for some of them to turn off their computers, and for others to put down their film cameras, and revisit some of the more traditional art forms that most here seem determined to eschew. Painting, still photography and sculpture are thriving in Britain but you would be hard-pressed to find them here.

Since the British Art Show’s inception in 1979, every five years different curators have taken on the challenge of presenting a snapshot of the contemporary art scene. This year curators Anna Colin and Lydia Yee selected 42 artists, bravely opening up the doors to designers as well as several collectives. Part of the Hayward Touring Programme, British Art Show 8 premiered in Leeds City Art Gallery and will travel to Norwich and Southampton after Edinburgh. It hopes to highlight artists before they become household names, and its roll-call of alumni, including Anish Kapoor, Sarah Lucas and Damien Hirst, prove that to be the case.

There are many highlights; top among at the Scottish National Gallery must be Rachel Maclean’s Feed Me, an engaging hour-long film juxtaposing sickly sweet colours with nightmarish imagery. Maclean, always centre stage, plays multiple roles in the film, which examines the nature of adolescent innocence alongside shocking moments of precocious knowingness. This is a film worth sitting through and an artist we will be hearing more about.

Andrea Büttner has mined the internet for images to accompany her exploration of Immanuel Kant’s Critique of the Power of Judgement. One of several works that is based on archiving, it seemed sadly more worthy then gripping to me. John Akomfrah and Trevor Mathison’s film also explores archival material, in particular the juxtaposition of image and sound. Laure Prouvost’s installation Hard Drive is activated by the movement of the viewer. We are invited to enter and sit on one of the benches, a gravestone by another British Art Show contributor Alan Kane. Prouvost speaks to us while electric fans and spot lights bedazzle and confuse.

When I ask Yee whether she and her fellow curator Colin are imposing lengthy works on the visitor, she responds that film is one of the most vibrant areas of practice at the moment and it is up to the viewer to decide on how much they choose to watch. She points out that the vast majority of non-art viewers feel more comfortable with film as a medium to engage with. There is a large proportion of film and installation work across all the venues and, sadly, only a very small smattering of sculpture and painting. For me, the amount of time spent in darkened rooms seems much too high.

Yee dismisses my criticism, saying that contemporary artists have largely moved away from more traditional, studio-based practices. Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, however, gracefully proves that painting can still be relevant, in a beautiful suite of recent canvases in the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art.

Her figures are drawn from the imagination, often in one day, and show a loosening of paint and an ever-growing fluidity of materials. Nearby are large conceptual paintings by Jessica Warboys made on the beach, with pigments scattered on canvases that are then washed by the waves into interesting patterns. Accident and incident inform these dramatic works.

I think a trick has been missed here by not including other painters and sculptors with which England is awash. Why not throw Rose Wylie, Sarah Barker or Chantal Joffe into the mix?

The Talbot Rice Gallery within the university gives generous space to Benedict Drew, a musician by training who has benefited from the placement of Sequencer in the large Georgian Gallery. The word “dystopian” is freely bandied around in this show and it does seem a particularly apposite description of this work. What was a smallish installation in Leeds has blossomed in a much larger space. I can imagine visitors losing themselves in time and space.

Ryan Gander’s large installation Fieldwork, also in the Talbot Rice Gallery, reveals playfulness and morbidity in equal degrees as a revolving track of objects presents itself. This diverse collection includes the urn that had contained his Auntie Deva’s ashes and a group of Playmobil “Mix ‘em Ups”.

Fieldwork is accompanied by an “incomplete reader” with notes by Gander on the individual objects, including a description of Ryan and his son’s experiments to make the Playmobil shed its identity, assembling the pieces by chance. I challenge anyone with children not to be moved by both this description and the objects themselves.

Pablo Bronstein has at last found his ideal setting in the central room at Inverleith House, the classical building in the centre of the Edinburgh Botanical Gardens. Bronstein’s continued exploration of architecture translated into dramatic monochromatic neoclassical wallpaper seems like it was always meant to be installed here, framing his large architectural drawing.

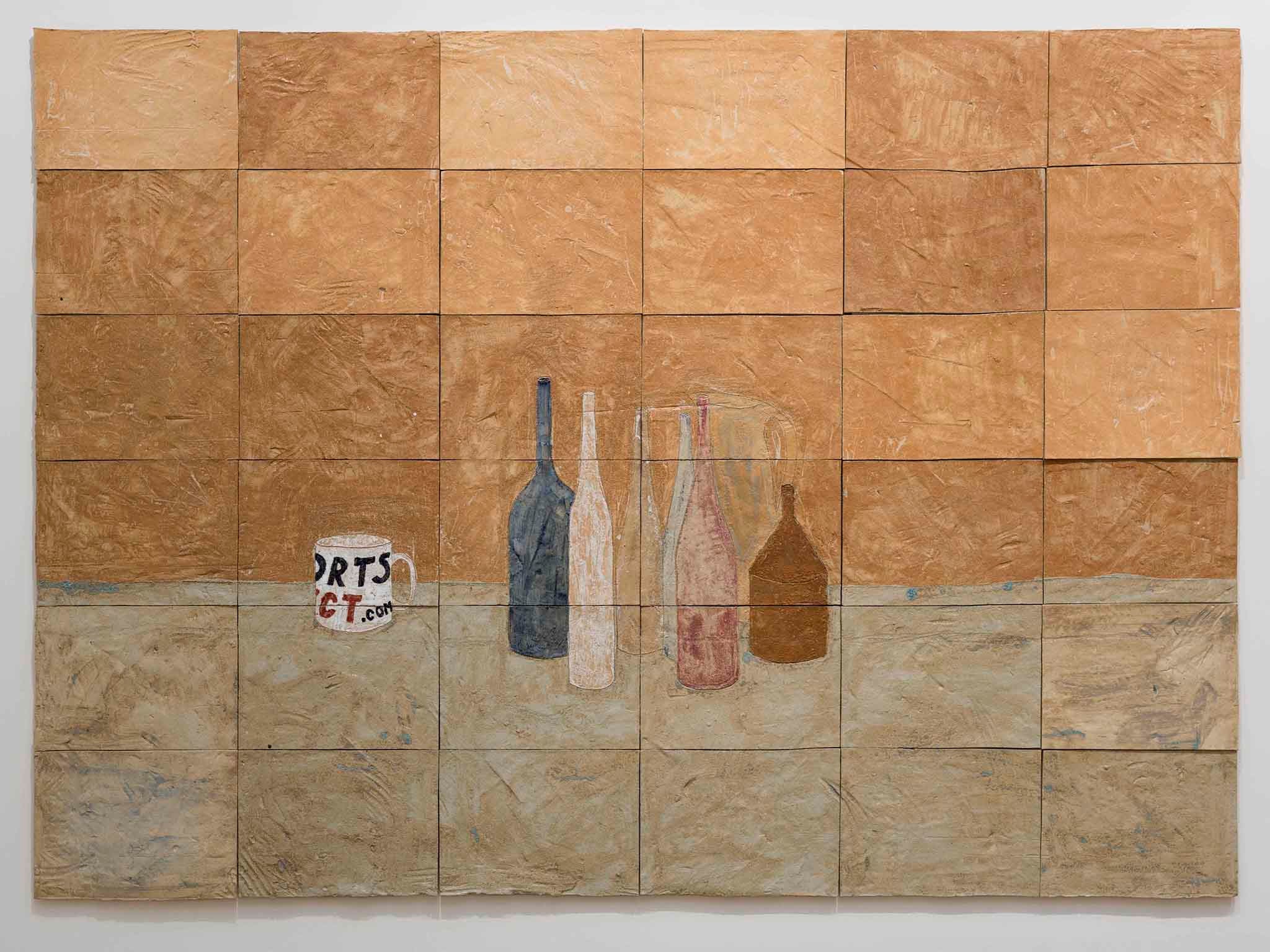

Jesse Wine, a ceramic sculptor, has spread out into the grounds of the Botanical Gardens and the large glasshouse. Seeing the ceramics suspended among verdant foliage is well worth the trip. Wine utilises ceramics in all its possibilities. Whether it is The Whole Vibe of Everything, drawn from an ancient screen, or Still Life, a group of Giorgio Morandi-like bottles, Wine pillages and integrates his own riff on the subject; a coffee cup from Sports Direct humorously completes the almost too polite image.

Inverleith House also houses Patrick Staff’s ambitious film The Foundation, shot in the Tom of Finland Foundation in Los Angeles. Tom of Finland was an artist whose death in tragic circumstances has fuelled interest in his overtly homosexual imagery. This is a film that will polarise its audiences, but is worth a viewing.

Inverleith House is a venue that always punches above its weight. With only two staff, it has the most sublime setting of any space in Edinburgh and far beyond. Caroline Achaintre’s shaggy tapestries made using an old-fashioned tufting gun have an eerie presence. Sharing her space are Ant Farm, two large Perspex sculptures by Anthea Hamilton. Both contain colonies of ants, which are injected into the sculpture to become a quasi digestive track for the work. Why would any self-respecting ant want to be injected into a Perspex sculpture? How can they be expected to thrive sealed within? Call the RSPCA, ants are being abused by the contemporary art world.

The generosity of size of the venues has produced a show that is miles in ambition from its initial display in Leeds, and will change again for its reinstallation in Norwich and Southampton. The stars of the show may ultimately be the venues. Eileen Simpson and Ben White’s Open Music Archive, an ongoing project to disseminate out-of-copyright music, may have a serious purpose but installed in the lofty upper space of the Talbot Rice Gallery the viewer my well prefer to enjoy the architectural majesty of the chamber than think too deeply about the work.

The views from Inverleith House, even obscured for film, remind us of how special this site is and of the beauty of Edinburgh; if one manages to trip over an interesting bit of art while there – all to the good.

British Art Show 8, Scottish National Gallery, Inverleith House & Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh, to 8 May (britishartshow8.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments