Blind artists and a unique vision: The visually impaired artists using tech to see things differently

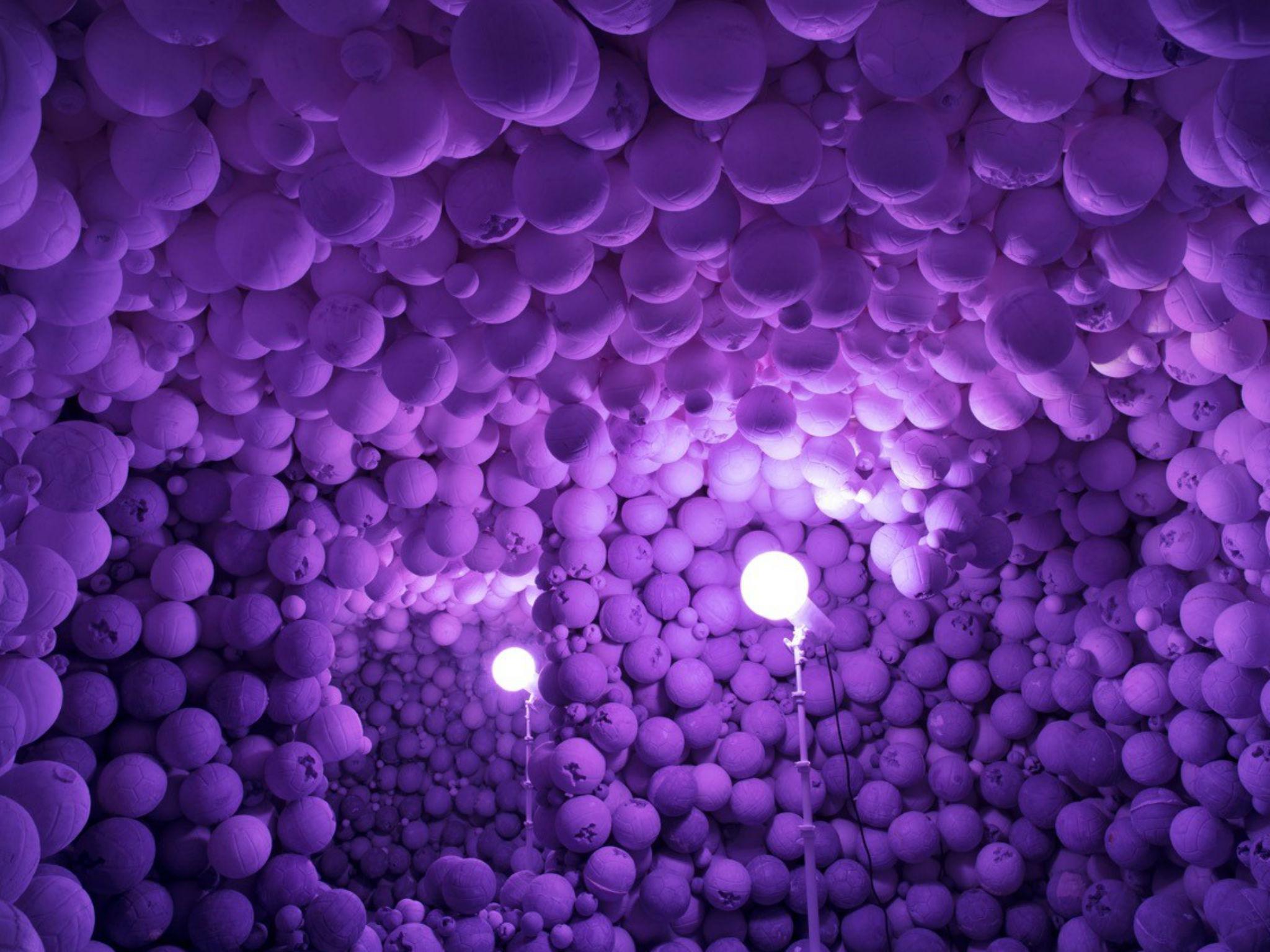

Daniel Arsham is colour-blind and his work is famed for its neutral palette. But that’s all changed for his first show of works in colour, opening at New York's Galerie Perrotin

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The art critic John Berger’s seminal book Ways of Seeing is required reading for art students. But what if you can’t see? Or if the way you see is quite literally different from the way other people do?

New York-based artist Daniel Arsham was born colour-blind. So it follows that his chosen palette is varying shades of monochrome. But with the help of new technology, he’s started seeing more colours and is staging his very first exhibition featuring brighter hues as a result of the markedly different way he has begun to view the world.

“Wearing these glasses [made by EnChroma], I’m able to see a wider range of colour. What the glasses do is they artificially expand the colour spectrum in the wavelengths that I am missing. And hence it has impacted my options for palette,” he told The Independent.

“So it’s not to say I will continue making all of my work in these vibrant hues; it’s just that it’s expanded the potential.”

You can see the impact failing sight has had on major artists from Van Gogh to Monet. It is hard to even imagine the emotional struggle the potential loss or diminishment of eyesight would have on someone who looks at things for a living. But Arsham is inspired by one of his artist friends who went blind after being hit by a truck while cycling in New York City.

“A very good friend of mine, and somebody who’s worked in my studio for many years, was blinded completely in an accident six years ago. Her name is Emilie Gossiaux and she is an artist and she works in the studio every day,” Arsham says.

“Being around her and seeing how she’s sort of brought the lack of sight into her work in really interesting ways has kind of further eliminated, for me, how this idea of sight and how individual perception really can impact how one sees my work, and art in general.”

Like Arsham, Gossiaux uses new technology to assist her sight. It is called a BrainPort Vision Device and it relays visual information from a camera through her tongue to the visual receptors in the brain. She is a wonderful ceramicist and sculptor, but has recently begun using the futuristic tech device to do what she did before her accident: put pencil to paper.

“I actually used (the BrainPort Vision Device) to draw,” Gossiaux said in a recent interview. “Every weekend I have all this time to myself so I set up a table with a gigantic, bright spotlight and I would draw in my 18X24 drawing pad. I would just draw there for hours, learning how to use it. Whatever images I had in my mind, I would sketch it, like doodles. I wasn’t drawing anything from life but more like cartoon doodles. That was always the way I enjoyed drawing.”

New York seems to be the place to be a visually impaired artist because another up-and-coming name on the Manhattan block is Neil Harbisson, whose dedication to using a computer that corrects his colour blindness is such that he had a microchip inserted into his skull. He has an antenna curving up from the base of his neck over his head, ending in a device at the centre of his forehead that acts as a third eye. He has nicknamed the device his “eyeborg” and refers to himself as the world’s first cyborg artist.

But unlike Arsham’s glasses, the “eyeborg” doesn’t give Harbisson the opportunity to see more colours in the world around him: it actually translates sound into colour. So while he still sees the world in greyscale, his third eye uses a computer programme to turn noise and music into colours, and can even go beyond the colour spectrums of human eyes allowing him to hear infrared and ultraviolet. His is the ultimate exercise in synaesthesia.

The Belfast-born 32-year-old believes artists have a duty to use technology to get beyond the limitations of our senses. “Becoming a cyborg isn't just a life decision,” he told The Guardian. “It's an artistic statement – I'm treating my own body and brain as a sculpture.”

I often argue with my sister about whether something is green or blue. And the debate over whether we see colours the same way has raged since way before Descartes started meditating on it. The online frenzy over “The Dress” sparked such a reaction because it revealed how our brains can be tricked into seeing colours differently. Which is surely why artists, who like to trick and be playful with our perceptions, find such interest in this.

Arsham feels that his colour blindness is a gift rather than a limitation. And, like the blind man of the proverb, whose eyesight was restored only for him to grieve for the beauty he had imagined rather than the reality of what was in front of him, Arsham isn’t sure he wants to see all the colours in the spectrum.

“In the beginning when I received these glasses, I was really excited about it. And I did feel that it would be some sort of profound, kind of life altering experience, and I would say in some ways it was,” he says.

“I wore them all the time for the first couple of months but I’ve now stopped wearing them regularly. I used them within the studio to see what everyone else is seeing, and then I am able to take them off once I’ve selected the palette. In some ways I do think that I certainly prefer to see the way I’ve always seen, because for me it feels right.”

Daniel Arsham: Circa 2345 is at Galerie Perrotin, New York until 22 October (opened today)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments