Artist Olafur Eliasson's latest large-scale works are inspired by the paintings of JMW Turner

Eliasson's works will go alongside a new exhibition of the great master at Tate Britain. He tells Jay Merrick why the paintings of his hero are ripe for reinvention

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

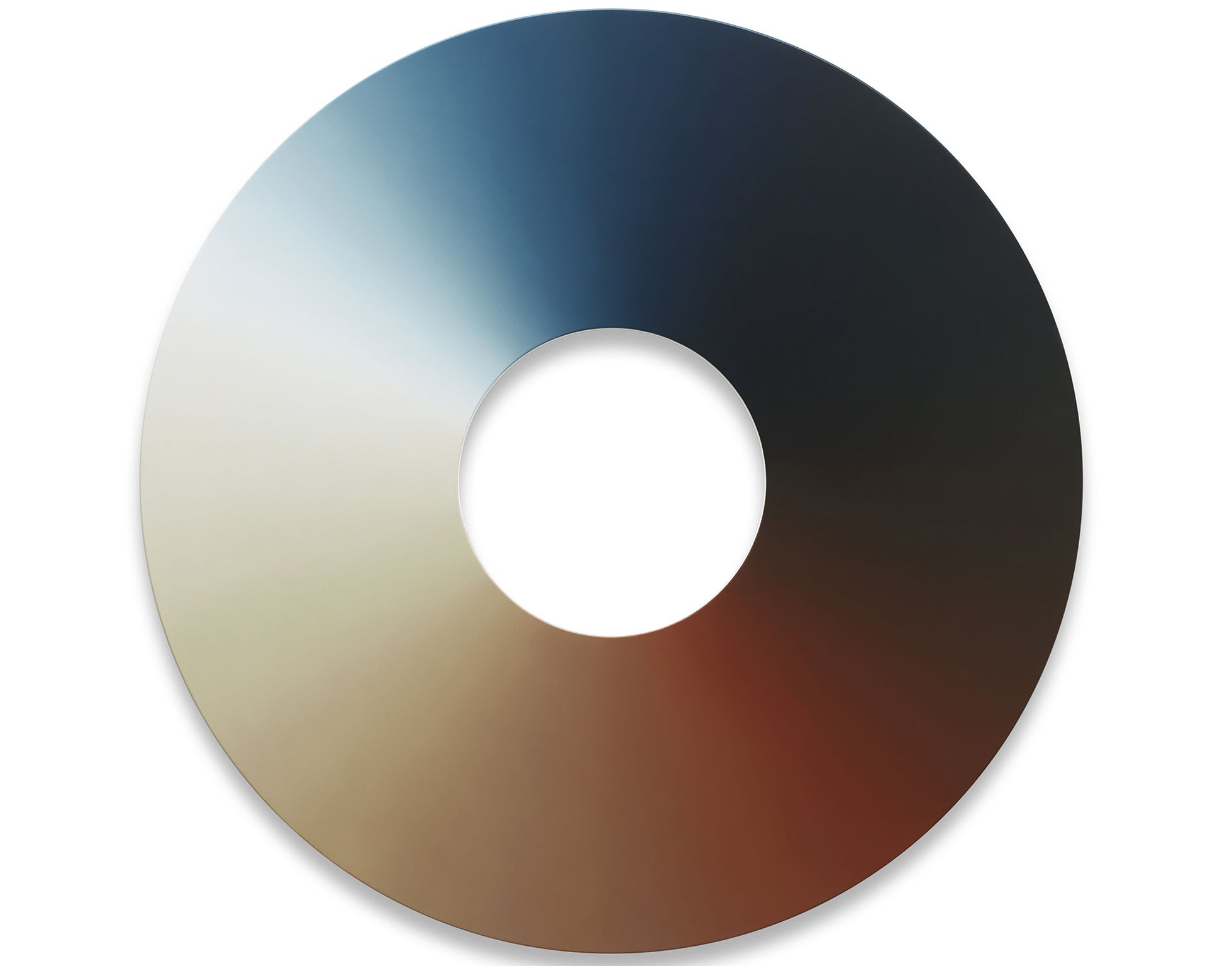

Your support makes all the difference.What can seven big circular paintings by Olafur Eliasson, which look rather like giant designer-coloured CDs, have to do with Britain's greatest and most visionary painter, William Turner? Eliasson's Turner Colour Experiments are the support act for the blockbuster Turner show at Tate Britain in September. The connection between the 19th-century genius and the 47-year-old, one of the most feted artists of his generation, can be summed up in a single word: ephemeral.

Not ephemeral as in our pixellated, fibrillating world of next-up, whatevers, and microsecond stock-market differentials. The presentation of ephemeral effects is central to both Turner and Eliasson, whose approach to art, and space, is invariably about ambiguous dematerialisations and states of flux. And in this sense, Eliasson, born in Denmark to Icelandic parents, falls into the same category as the Impressionist painters, whom Turner influenced, and the more exploratory postmodern artists and architects such as James Turrell and Jean Nouvel.

In Eliasson's case, there's a socio-political dimension to his expressions of the ephemeral. It originates in his fear of the effects of consumerism, which he says "packages experiences for sale" and produces what the art historian Barbara Maria Stafford describes as "a seamless spectacle of [artistic] goods". Eliasson creates ephemeral, perceptually disruptive artworks to counter the effects of soul-deadening consumerist ephemera.

His profound interest in the social, sensual, and political aspects of perception make him a 21st-century doppelgänger of the 19th-century Turner. Eliasson is all about creating experiences that rip the shrink-wrapping off pre-conceived reactions to colour, space, materials and time. He's challenging our sense of both democratic and individual existence.

He achieved this most brilliantly in 2003, when more than a million people wandered in the unearthly ochre light of the vast "sun" of his Weather Project installation at Tate Modern. Everything – the Turbine Hall, the light, people – seemed simultaneously lusciously beautiful and utterly alien; it was the art-going equivalent of a silently ecstatic rave. And it radiated a literally Turneresque vibe, recalling paintings such as Shade and Darkness from 1842; chrome yellow was, of course, Turner's favourite paint colour.

Eliasson's fascination with Turner dates back to his artistic beginnings in the late-Eighties and early-Nineties. "There was a financial crisis then and we [student artists] were obsessed with dematerialisation and ephemera.

"When I was looking at Turner, I was looking at the dematerialising of social constraints of his time. He was introducing an atmosphere, and a critique of other painters. I saw Turner as aesthetically touching, and also as a social activist."

Around us, gallery staff were putting the finishing touches to Riverbed, his startling new installation at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, north of Copenhagen. Nine container-loads of black Icelandic basalt – "they cost less to ship than sending nine paintings to ArtBasel" – have been used to create a kind of glacial alluvial scree that cascades through several galleries. The effect, he muses approvingly, is "brutal".

Some might say the same of Turner's later works, notably the apparent chaos of paintings such as Sun Setting Over a Lake and Snow Storm, from the early 1840s. But it's not this superficial wildness that Eliasson has responded to with his Turner Colour Experiments.

His new series is meant to incite what he calls "co-production", the continuous oscillation between people as private beings and as participants in a collectively created reality. Not collective as in experiencing the art in similar ways, but collective as in responding to it very individually. He describes co-production as "a mild attack on the ever-increasing experiential numbness that society produces in abundance."

The Turner Colour Experiments express the fusion of Eliasson's social concerns and his desire to derail our senses of colour, time, place and emotion so that we are forced to personally reinvent what we're looking at: "When I look at Turner's paintings, I think of an orchestra of colours. You can see space, and you feel atmosphere. And you take it upon yourself to co-create it. I was longing to throw myself into these Turner paintings."

Eliasson's paintings take the light and colour from each of seven of the master's works – they include The Burning of the House of Lords and Commons, A Disaster at Sea, and Breakers on a Flat Beach – and then re-expresses them in extremely subtle circular chromatic riddles. Eliasson speaks of transforming the painterly essences of these works, not into something worthily "interesting" or desirable, but to generate a sense of endless visual movement that doesn't allow the viewer's eyes to settle. "Why did I pick these seven? I wanted pictures where there was a process of dissolving."

And that quality of movement is designed to give the paintings a dynamic, living sense of time. It's not a difficult concept: paintings by Giotto or Nicolas Poussin, for example, are exquisite but seem frozen in particular moments; Turner's Rain, Steam and Speed – the Great Western Railway and Van Gogh's Wheatfield with Crows do not.

The essential humanism and carefully conceived sensuality of Eliasson's art has nothing to do with a clichéd "genius-at-work, anything might happen" creative situation. His works, and the physical and perceptual disturbances they create, are generated by a scientifically inclined intellect. In the case of the Turner Colour Experiments, painstaking precision has gone into producing deliberately imprecise effects.

Like Turner, Eliasson is fascinated by colour combinations, and by contrasts of light and darkness. His research, over the last six or seven years, has been obsessive – nanometers used to measure variations in the colour spectrums of white light in places including Venice, and close examination of the qualities and effects of light and shadow in paintings by Canaletto and Vermeer. He's bought pigments from all over the world in an attempt to create a hyper-detailed breakdown of the red-to-violet range in the light spectrum.

In the case of the Turner colour experiment paintings, Eliasson worked with high quality reproductions of his seven chosen Turners. Two members of his Berlin studio with "amazing skills" were key to the process: they isolated more than 60 individual colours in each painting. These colour sets became the equivalent of palettes, and were used to create what Eliasson thinks of as Turneresque colour-wheels. "We toned the colours up, or down, until they looked in synch," he says. The amount of light and shade on the canvas-covered aluminium stretchers was balanced in the same way.

"The potential of painting lies in the potential of the way you can finish it," says Eliasson. "That's the relevance. Turner would want us to be in a constant dialogue with his paintings. That's what I find so trustworthy about him – his paintings can hold two viewers in front of them, which they're disagreeing about. Turner's paintings are really contemporary. It's so lovely that he clearly entreats you to finish his paintings."

The result, via Eliasson: seven big swirls of colour, in superfine detail, on seven big disks, in homage to the mysterious centrifugal force-field effects that characterised William Turner's most compelling paintings. Will we feel entreated to finish Eliasson's offerings? If we do, then Turner's ghost might think Olafur Eliasson was trustworthy, too.

Olafur Eliasson: Turner Colour Experiments & the EY Exhibition: Late Turner – Painting Set Free, Tate Britain, London SW1 (020 7887 8888) 8 September to 25 January 2015

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments