Art exhibition On Their Own shows the heartbreaking history of British child migration

They were sent abroad for a ‘better life’, what they found instead was abuse and forced labour

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.You could easily mistake the photograph of four young British children carrying massive suitcases that are almost as big as they are for a happy holiday snap. But these are children from deprived homes in the UK who in 1938 are being shipped off to Australia, to Fairbridge Farm School in Molong, New South Wales, to be used as child labour.

In another group shot, about 40 British boys are standing by the SS Asturias, having arrived in Fremantle, Western Australia, in 1947. It’s a poignant picture; after it was taken, siblings were separated from each other according to their age, and sent to different Christian Brothers institutions, where sexual abuse was commonplace.

In another photograph, teenage boys stand on scaffolding on a building at Bindoon Boys Town, Western Australia, in 1952. Here children were expected to contribute to the construction of their school, and consequently made little progress in their education.

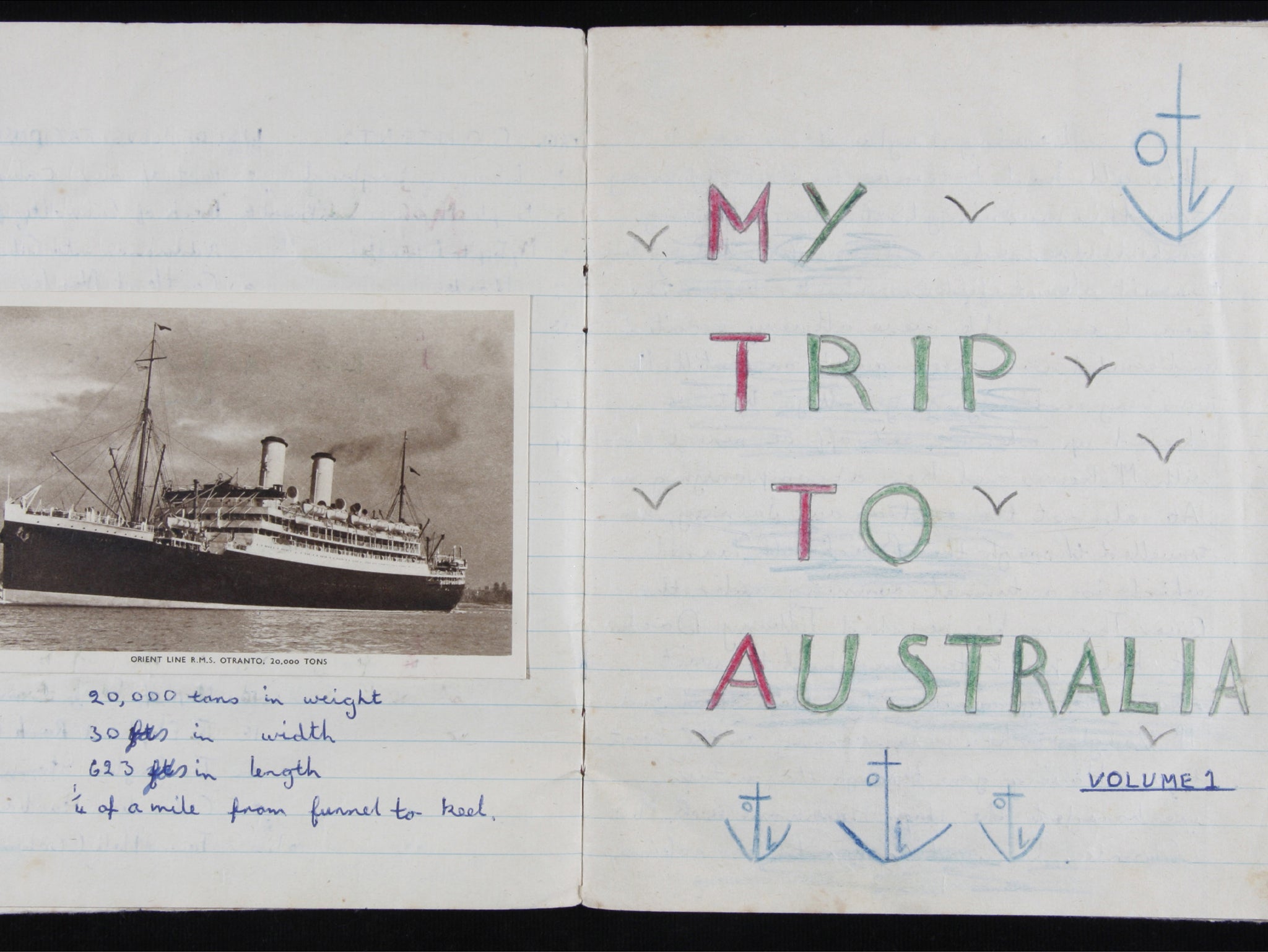

A notebook kept by a child migrant named Maureen Mullins opens with “My trip to Australia” written in brightly coloured pencils and a photo of the ship SS Otranto that took her to her new life in Australia, aged just 12.

In most of the institutions the children were sent to, there was a lack of emotional nurture, and often sexual and physical abuse.

A new exhibition at the V&A Museum of Childhood, “On Their Own: Britain’s child migrants”, charts the heartbreaking history of child migration from Britain to her overseas colonies between 1869 and 1970.

Photographs and personal items, as well as case studies from surviving child migrants, explore the stories of children as young as four being packed off to Canada, Australia and other Commonwealth countries. As many as 100,000 children, from poor or broken homes, were sent abroad in search of a “better life”, as part of misguided humanitarian schemes.

It was only in 2010 that the then Prime Minister Gordon Brown issued an official apology for the “shameful” child resettlement programme and announced a £6m fund designed to compensate the families of child migration schemes. The Child Migrants Trust has since set up the Family Restoration Fund to use this money to help reunite former child migrants with their families, as part of the British government’s package of support.

A recent settlement of A$24m has just been awarded to former child migrants sent to Fairbridge Farm School from the UK as part of the discredited child migration policies. This sum is the highest compensation settlement in Australian history for a case of historic institutional abuse.

“While presented as being in the best interests of the child, the schemes were also intended to build up the British Empire with ‘good British stock’,” says Gordon Lynch, who is the Michael Ramsey Professor of Modern Theology at the University of Kent and researches schemes run by charities and churches that removed children from their families or local communities. His book Remembering Child Migration is due to be published by Bloomsbury in early 2016.

“The receiving countries also saw these children as an important way of building up their future workforce,” he says.

Items in the exhibition will include a wooden travelling trunk used by a child migrant from Quarrier’s Homes, Scotland, for travel to Canada. Tools on display include a scythe, mattock and sickle from Fairbridge Farm School, used by child migrants from the 1930s to early 1940s.

A painted solid ceramic double-storey miniature house has an inscription on the base that reads “WADE IRELAND”. It was purchased by Pamela Smedley, a child migrant, with her first pay, to remind her of Britain. In 1949 the 11-year-old Smedley was told she was being sent to Australia for adoption. However when she disembarked SS Ormonde in Adelaide, she was taken to the harsh Sisters of Mercy’s Goodwood Orphanage.

In 1989, she contacted the Child Migrants Trust who helped to reunite her with her mother, Betty, who believed that Pamela had been adopted by a loving family in England. In 2010, Smedley was invited to the UK to witness Gordon Brown’s historic apology to former child migrants at Westminster.

“Some families placed their children in schemes like Fairbridge having been persuaded that their children would have better opportunities overseas,” says Lynch. “Other parents left their children in Catholic children’s homes in Britain not realising their children would be sent to children’s homes overseas without their knowledge.”

While the child migration schemes originated at a time when child welfare support in Britain was inadequate, by the end of the Second World War, the schemes were “increasingly running against the grain” of accepted childcare practice, says Lynch.

“What is particularly disturbing is how much was known about the poor conditions and often brutality the child migrants were subjected to –but no effective action was taken to remedy it.”

‘On Their Own: Britain’s child migrants’, V&A Museum of Childhood, London E2 (vam.ac.uk/moc), 24 October to 12 June 2016

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments