Anxiety attack: Faces from the fin-de-siècle

An exhibition of turn-of-the-century portraits reveals troubled times

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.We call it the fin de siècle, a ripe age of dreamy literature, days in coffee houses and nights of wine and roses. It was a careless time, a peaceful time, when summer looked set to last forever and everyone was blind to the cataclysm looming over the horizon. That, at least, is the received wisdom on the opening of the 20th century.

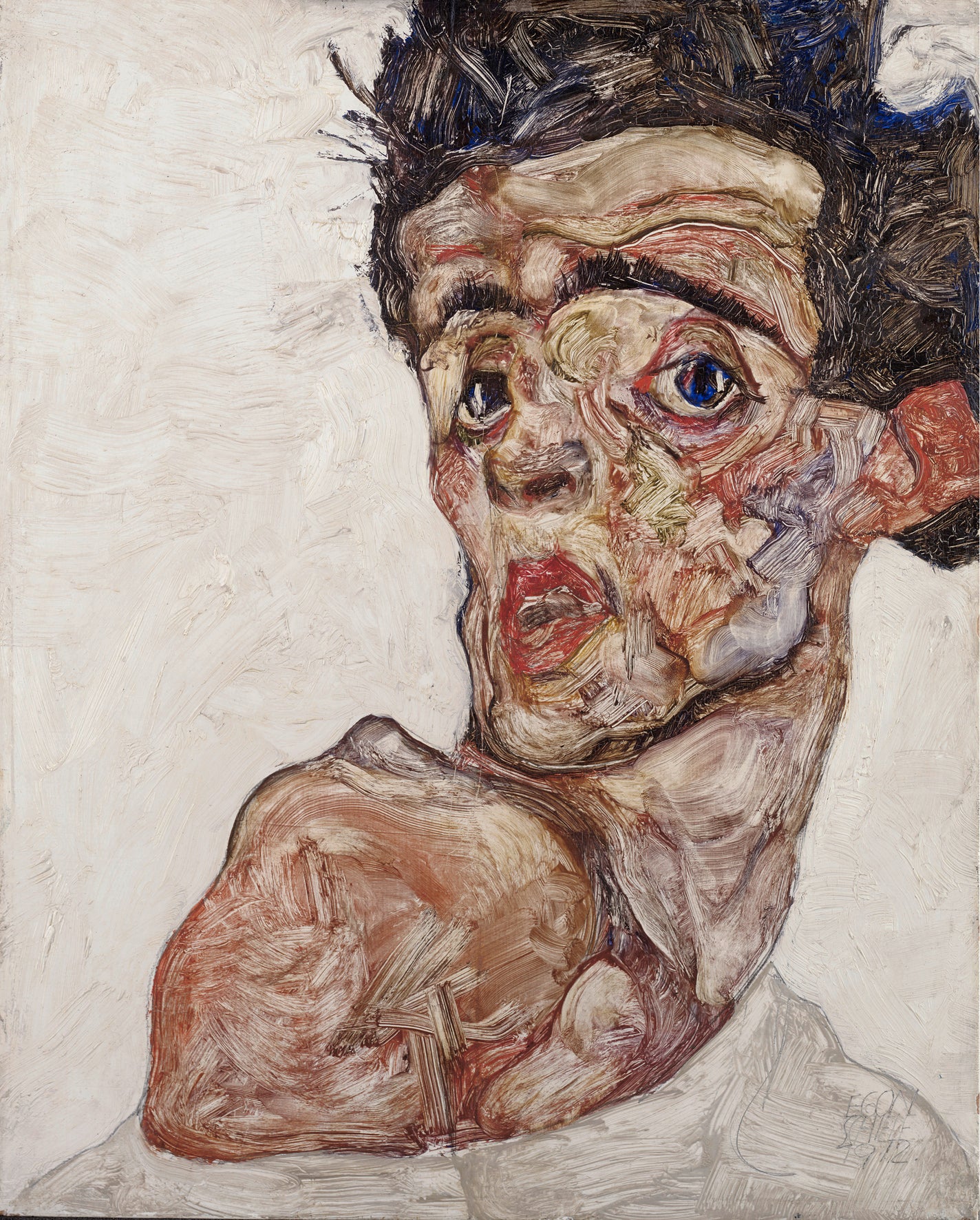

But if you look closely at the National Gallery’s new exhibition, Facing the Modern: The Portrait in Vienna 1900, you’ll discover a very different story. Displaying portraits from the capital of the Austro-Hungarian empire in the period before the Great War, and the empire’s collapse, when Gustav Klimt and his acolyte Egon Schiele dominated the city’s visual arts, Facing the Modern does not bid farewell to a golden age; it brandishes the gun out of which the 20th century was fired.

Vienna, situated at the heart of Europe, was the epicentre of this extraordinary but unrecognised period of social and cultural change. The city exerted a gravitational pull over vast swathes of the continent’s population. When Austria-Hungary declared war in 1914, Vienna was one of the 10 largest cities in the world; now it doesn’t feature in the top 200.

Facing the Modern begins in the mid-19th century, at which point Vienna was fundamentally a conservative place. Its unchanging hierarchy, with Emperor Franz Josef at the top, filters down through the ranks and riches of the paintings featured in the exhibition’s opening rooms.

The vivacious Gustav Klimt, born in 1862, was a product of those crinoline-clad times. Having studied at the School of Arts and Crafts in the early 1880s, he cut his teeth painting murals in the palaces along the Ringstrasse, the city’s new civic boulevard. Yet that impervious world of ballrooms, waltzes and whipped cream was about to face a major challenge to its authority.

Encouraged by Freud’s exploration of the unconscious sexual roots of neurotic behaviour, as well as Otto Wagner and Adolf Loos’s abolition of historicist decoration from architecture, a new questioning, artistic generation began to scratch at the veneer of Habsburg pomp and power. Klimt was keen to play his part.

The disparity between the establishment and the intelligentsia became ever more pronounced during the final years of the 19th century. In 1897, right-winger Karl Lueger became the mayor of Vienna. Blaming liberals and Jews for the financial crash of 1873 and the subsequent recession, Lueger established a much narrower world view among the everyday Viennese. But in the same year, Klimt and other artists formed the Secession, an avant-garde group opposing the city’s dictatorial arts association the Künstlerhaus.

The tension between these camps seethes beneath the glitter of Klimt’s paintings, not least his 1904 portrait of Hermine Gallia. She may be a veritable dream of lace and tulle, but her pulled-up bearing and tightly clasped hands are far from serene, as if the advent of Lueger, electric trams, the telephone and neurasthenic investigation has frozen her solid. And even when Klimt and Schiele liberate their subjects from corsets and collars, risking the indignation of the authorities, those pressures remain. Indeed Schiele’s self-portraits are the most anxious works in the exhibition.

The composer Gustav Mahler’s death mask, also displayed, shows an even more overwrought face. Hounded out of the directorship of Vienna’s opera house by a vicious anti-Semitic campaign, Mahler left the city in December 1907 for fresh challenges in New York, only to succumb to a fatal heart condition. You can perhaps hear those strains in Mahler’s music, but you can certainly see them carved into the lines of his face.

No wonder Mahler looked so harassed. After an exhausting career, the death of his daughter and the discovery of his wife Alma’s affair with the architect Walter Gropius, his final weeks proved even more gruelling. Journalists covered every inch of his journey back from New York to the private sanatorium in Vienna, where he died on 18 May 1911. Registering Mahler’s temperature, diet and mood, their twice-daily reports rivalled the most invasive celebrity-obsessed journalism of today.

Such events provide just one parallel with our own fin de siècle. What else are the YBAs and the Arab Spring if not equivalents of the Secession and the nationalist tensions within the Balkans in 1914? And we are still debating the pros and cons of a unified Europe, though empires have since become republics and rulers and borders have changed.

Gazing into the eyes of Klimt’s Ringstrasse princesses or Gyula Benczur’s portrait of Empress Elisabeth, you may think that Facing the Modern has nothing to do with today. Yet the distance we feel between now and then is symptomatic of the moniker we have given to the period. We have chosen to view it as an ending rather than a beginning: the last unclouded afternoon before the guns of the Somme drowned out “The Blue Danube Waltz” and Mahler’s elegies. But the urgent culture hidden within this exhibition contradicts every one of these nostalgic impulses.

While the Austrian social reformer Rudolf Steiner, like many of his generation, saw decadence all around, he also realised that the era marked a beginning. “For in those dying forces,” he wrote, “we finally sense, even see, the forces preparing themselves for the future, and in the sunset, the promise and hope of a new dawn”.

Some of the seeds sown in Vienna at that time grew into bitter crops – Hitler, Stalin and Trotsky walked the same avenues as Klimt, Mahler and Freud. Reconciling these factions can be difficult. But in the expressions and manners of Facing the Modern we are able not only to understand the century that has elapsed since the fin de siècle, but also to glean some insight into the time in which we now live. In our end is our beginning.

‘Facing the Modern’ is at the National Gallery from 9 Oct to 12 Jan 2014. Gavin Plumley will give a lecture to accompany the exhibition on 7 Oct at 1pm.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments