Allen Jones: The model of misogyny?

At a retrospective of the 77-year-old Pop artist Allen Jones, Zoe Pilger finds that she is at once offended by his objectification of women and fascinated by his strangely seductive works – including a bionic Kate Moss

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In my novel, Eat My Heart Out, a deranged second-wave feminist called Stephanie Haight owns a series of rip-off Allen Jones sculptures.

These Pop art pieces, made in the late Sixties and early Seventies, consist of fibreglass female models posed as items of furniture. Stephanie says: “I don’t know if he was being ironic or just straightforwardly offensive.”

Now 77, the British artist’s retrospective has just opened at the Royal Academy, London. It is offensive, but also fascinating. The first gallery gives people what they want: here is Table (1969), a life-size, pornographically perfect woman on all fours; she wears knee-high boots with spike heels, black gloves, a black corset which displays her balloon-like breasts. To make her and other works like Chair (1969), Jones worked with a company that produced waxworks for Madame Tussauds.

Significantly, a hand-mirror is positioned on the rug beneath her, and she stares at herself. She is frozen in a position of submission and vanity. This is the age-old patriarchal vision of woman: born to serve, admire herself, be used. A glass surface is bolted to her back, transforming her into a coffee table. If woman has historically been aligned to the domestic, Jones turned her into a domestic object.

Jones has said that his aim was to create something with “an iconic presence,” and in this sense he succeeds without question. Nearly half a century after it was made, Table appears as fresh and powerful and grotesque as ever. While much of Pop art now seems tired, Jones created a singular visual language. Here is the female figure rendered abject and humiliated, a fact which is obscured by the brilliance of his design.

Stanley Kubrick approached Jones to design the set of A Clockwork Orange (1971), but he declined. Kubrick ripped off the designs instead. In the Korova Milk Bar, where Alex and his droogs drink milk laced with drugs, furniture comprised of painted white women adds to the ambience of “ultra-violence”.

Jones has called himself a feminist, but the sculptures were attacked by the new feminist movement that was emerging in the late Sixties and early Seventies. For me, they point to the contradictions of the idea of “free love” in which we are still mired. Second-wave feminism emerged alongside the “sexual revolution”, but the two shouldn’t be confused; the former demanded equal rights for women, while the latter encompassed Playboy and the birth of the modern porn industry, which glorifies male dominance.

Jones’ sculptures may be classified as “porno chic”, but what they show is sexual cruelty. Forniphilia is “the art of human furniture”, a word coined in 1998 by the fetish company of self-proclaimed “mad bondage scientist” Jeff Gord, who said: “I have always loved the thought of using women as items of furniture... I guess it is the thought of having such a powerful sexual being totally under control.”

There are precedents in art history: Salvador Dalí was photographed sitting behind a desk made up of a real woman for a 1947 photo shoot for Look magazine; François-Rupert Carabin used the female figure as a structural rather than decorative element in his fin de siècle wooden furniture. Jones seems as much influenced by the Modernists and Surrealists as girly magazines.

A display case in the second gallery is engrossing; it shows the cultural impact of Jones’ work. There is a vile cartoon that was published in The Daily Mirror at the time: a male visitor to Jones’ exhibition mistakes a real woman for a fibreglass one and ashes his cigarette in her shelf-like cleavage. Her husband grabs him and says: “That ashtray happens to be my wife!”

While Jones was part of the artistic avant-garde – along with Royal College of Art contemporaries Patrick Caulfield and David Hockney – the sculptures clearly appealed to regressive patriarchal taste, which was threatened by the new feminism. A 1969 photo shoot for Vogue shows Table and another sculpture, Hat Stand (1969), alongside Jones’ wife, Janet, who is blond and appears akin to the models. The effect is uncanny and sinister: real flesh appears interchangeable with fibreglass. The difference is not immediately obvious.

There are objects too from Jones’ studio: a tiny woman locked in a cigar jar, some soft-porn seaside postcards, and a gold Playboy bunny statuette of Marilyn Cole, Playmate of the Year in 1973. It seems dangerous to take these images too lightly, as mere relics of a sexist time. We still live in a sexist time; women are still the second sex, expected to be subservient to men’s needs. The feminist response should have been included in the display too.

The next gallery is a swerve from what visitors might expect: it is full of huge, vivid oil paintings, both abstract and figurative. What is striking is how the dark theme of sexual degradation is combined with a joyously colourful palette.

The subject matter is often clichéd: kaleidoscopic orgies in night clubs attended by glamour girls and jazz musicians. Indeed, much of it looks like a 1980s reimagining of the jazz era, with swirly indeterminate lines and airy expanses of colour. Many look like they could hang in Gordon Gekko’s apartment.

But there is something about them; they are eerie and seductive. Night Moves (1985) includes a mermaid nailed to a cross. This mythological creature has been crucified for her sins – what are they? Perhaps because she is beautiful and mysterious, she must be pinned down and hurt. Luxe, Calme et Volupté (1978) is a large painting that shows a woman’s long, supple legs. Her torso is covered by what appears to be an African mask and her head is not visible. She wears high red heels and anklets made of green leaves. A bongo drum sits beside her.

The work is named after a 1904 painting by Matisse, who in turn borrowed the title from a line of Baudelaire’s Flowers of Evil (1857): “There all is order and beauty / Luxury, peace, and pleasure.” The “order” in many of Jones’ paintings seems to refer to a timeless world in which women are happy to exist principally as objects of male desire. Here the motifs of what was once called “primitivism” suggest “exotic” fantasy. It calls to mind the 1920s posters of Josephine Baker in a banana skirt, with its colonial overtones of the sexy “savage”.

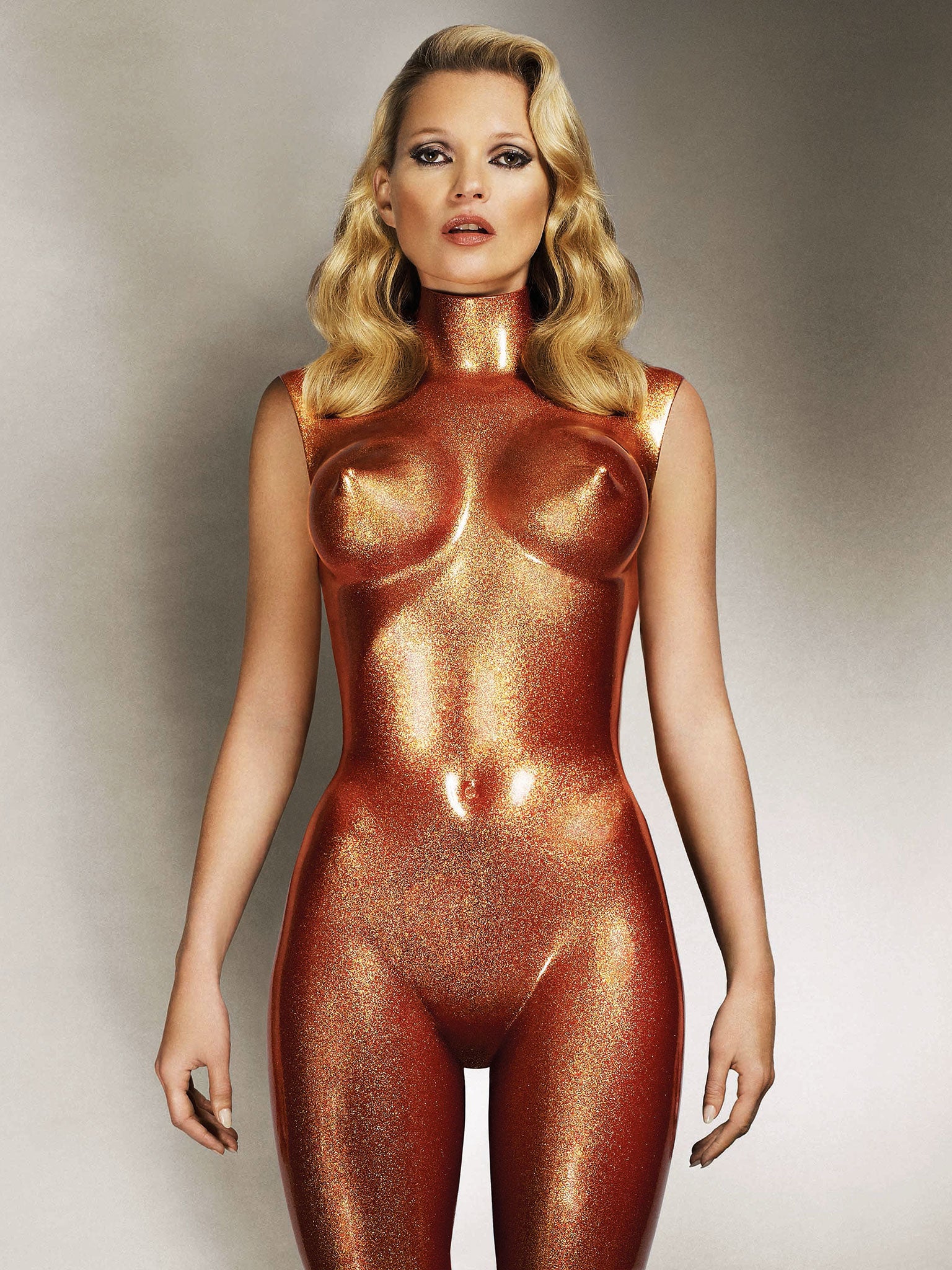

Things get weirder in the last gallery, which contains an army of fibreglass females, their expressions glazed and compliant. A Model Mode (2013) has the features of Kate Moss, but no arms; her Jessica Rabbit body has been squeezed into a strapless aquamarine fishtail dress that pools on the floor around her. It transforms her shape from a human into a mermaid.

The real Kate Moss stares out from a photograph on the wall; she wears one of Jones’ creations: a bronze glittery body-suit with no back, which transforms her idealised waif-like form into one of bionic pornography. Indeed, the principle of Jones’ work seems to be metamorphoses: women become more than women, divine and dirty at once.

The sculptures recall the blow-up girlfriends that you can buy on the internet. And yet, like the paintings, there is something about them. Their presence is unnerving. The famous Hat Stand is here; her mauve chiffon is complimented by steel-grey shoulder-length hair, which is incongruous. Perhaps the task of being a hat stand has aged her?

The image that stands out is Desire Me (1969), a small black-and-white watercolour. It is the only work in which the female subject stares back at the viewer with real expression. The title is a demand. Instead of female acquiescence, she is asserting her own desire. For this reason, she is shown as monstrous.

Allen Jones, Royal Academy of Arts, London W1 (020 7300 8000) to 25 January

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments