The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Portrait of a lady: the remarkable story of my godmother, the ‘last marchioness’

With its glittering cast of writers, painters, sportsmen and the ‘horrible’ upper class friends of her wealthy parents, hers was a gilded and privileged childhood. She married into the aristocracy, befriended David Hockney and survived devastating personal tragedy. Not that any of it impressed Lindy Dufferin, recalls Harry Mount

I often asked my dear godmother, the Marchioness of Dufferin and Ava (1941-2020), about her extraordinary upbringing.

What a gilded youth it was, as the daughter of Loel Guinness – a financier, MP and Battle of Britain pilot – and granddaughter of the Duke of Rutland.

The great American golfer Ben Hogan gave her golf lessons. Jacques Cousteau taught her to scuba dive, with baby aqualungs. Truman Capote befriended her as a little girl. “He was so wicked – I loved him,” Lindy said.

How dashing it all seemed. Lindy learnt to fly helicopters while sitting in her father’s lap but, as she put it: “I sometimes think he was better with machines than he was with women.”

She would politely tell me about the glittering cast list of her childhood with a touch of world-weariness. She never rejoiced in their fame and glamour. Instead, she was slightly depressed that people should be so interested in these often flawed, spoilt figures.

Lindy had known them all so well that she could take them at face value. When I once showed her a fawning book about her parents’ upper-class generation, she said: “What you must remember is that they were all horrible!”

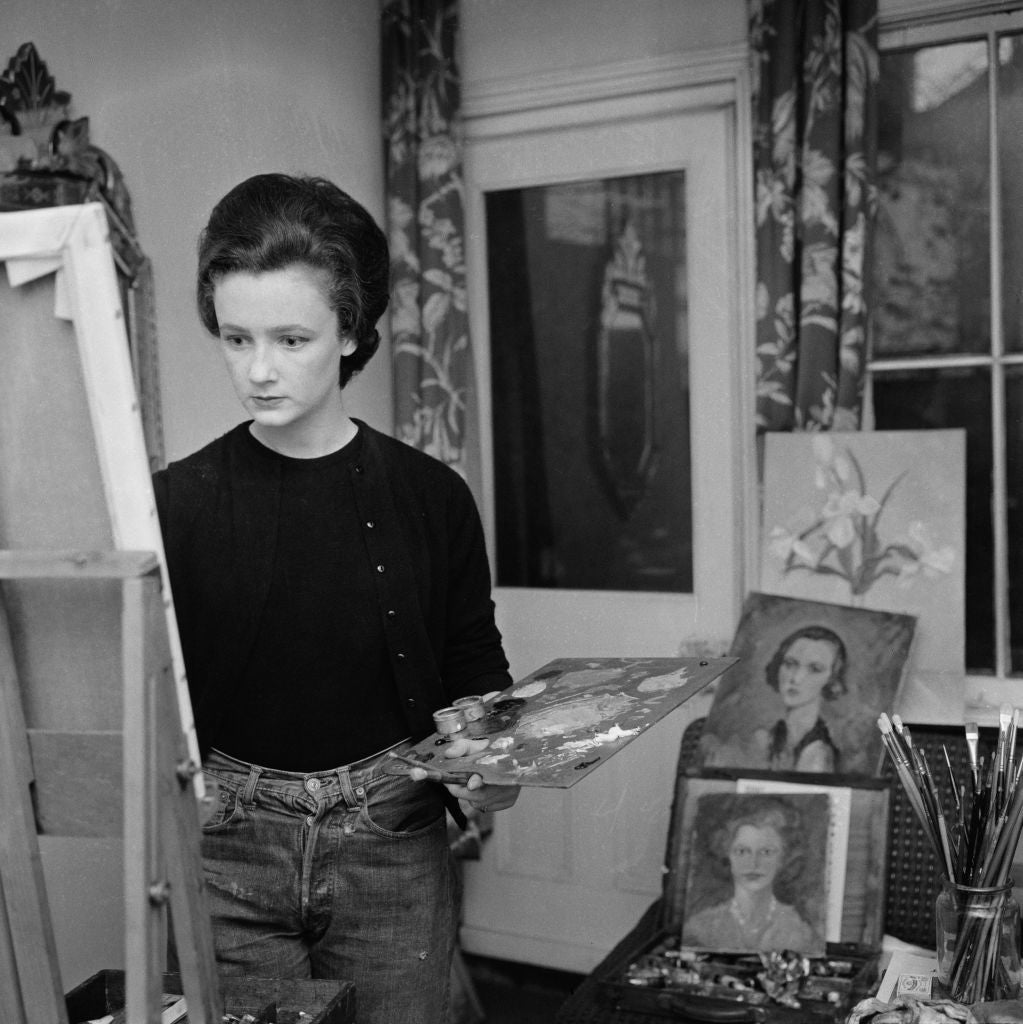

She found two refuges. First, the Bloomsbury painter Duncan Grant, who took her under his wing and taught her to paint when she was 17 and he was 74.

And then, in 1964, in the wedding of the year at Westminster Abbey, she found another refuge in her marriage to the Marquess of Dufferin and Ava.

Sheridan Dufferin had founded the Kasmin Gallery in New Bond Street with John Kasmin. There, in 1963, David Hockney had his first-ever show. Hockney became great friends with the Dufferins, painting and drawing them both several times. His most famous painting, A Bigger Splash, hung in their house for many years until Sheridan’s tragic, premature death at 49 from Aids in 1988, when it was sold to the Tate.

Hockney says: “I remember when Lindy was looking after Sheridan with his fatal illness – she really loved him.”

Lindy was always completely open about Sheridan’s death: that he’d had Aids; that he’d had gay affairs. She talked often about his bravery: how he’d never complained for a second as he lay dying; how he’d said to her that, after he was gone: “You can sell Clandeboye [his house and estate near Belfast] but I’d much rather if you didn’t.”

After a period of intense grief after Sheridan died, Lindy took up painting again with renewed verve and originality. It’s like the Old Testament story of the honey in the beehive that grew inside the dead lion – captured on the tin of Tate & Lyle golden syrup: “Out of the strong came forth sweetness.”

She didn’t just return to her painting with gusto. She also revitalised the Clandeboye estate. How she threw herself into the place, turning it into a hive of activity: less social – though she did host endless gatherings – than charitable and commercial. Every year – every month, it seemed – there was a new scheme.

She bred champion cows and made the prize-winning Clandeboye Estate yoghurt. The estate was often used for filming, including for Game of Thrones. She held cross-border reading parties for students from Trinity College Dublin and Queen’s University Belfast. She set up a forest school in the woods, where local children learnt about nature. She carved out new gardens, revived the Clandeboye arboretum and renovated Helen’s Tower, an enchanting folly on the estate.

With Barry Douglas, the leading Belfast pianist, she set up the Clandeboye Music Festival. This year’s event will take place at Clandeboye between 19-26 August.

And much of this was done to the background of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, which never unnerved her. She said: “Many of my English friends were deeply concerned about my security but understood I had total confidence about being both a Guinness and a Dufferin and was proud of both these cross-border connections.”

As my father, the writer Ferdinand Mount, a friend of Sheridan and Lindy, said on her death: “She stood dauntless through the worst of the Troubles, when the Paras were on the streets of Belfast and automatic weapons poked through the battlements of Derry. She made friends with pretty much every secretary of state and first minister of whatever party, from Peter Mandelson to Arlene Foster.”

On and on the entrepreneurial and charitable ventures popped up, driven by this wiry dynamo of a marchioness.

In her diary in 2018, she wrote: “I always wanted to be born a man because I hated having to play the part of a female – now I have this all by accident. I love it.”

Lindy had been brought up in a world where she was expected to marry well, not to be educated and not to work. With Sheridan’s premature death, she was propelled into the professional world, and she turned out to be a natural at it.

Viscount Gage, a friend of Lindy’s since 1954, said: “Lindy could have been a poor little rich girl, shuffled across the Atlantic with lawyers, with two angry parents.”

Instead, she recoiled against that cold, unhappy time and developed an unusual capacity for warm empathy. Maybe because she hadn’t had the happiest of childhoods in the grandest of families, she could see through gilt veneers. Out of the unkindness of that tricky childhood came kindness.

As she wrote in her diary: “I can remember Mummy in 1959 in Granny’s bedroom, saying I was useless and should do something – it was her who kept pushing me – thank you, Mum. I wish I could have been closer to you.”

The cruelty of her mother was replaced by Sheridan’s kindness, as she recorded in her diary: “Sheridan has allowed me to be exactly what I wanted to be. He knew that I had in me the desire to be like I am at this moment. If he had lived, I could not have been like this. Did he die because of me? That is a huge, vast question. If he was alive now, what would he say? ‘Dear, I love you. That is all you need to know.’ Then he would go back to reading a bridge puzzle.

“It was a wonderful mind – and he really loved me – if he could see me now – perhaps he can – if so, I would evaporate into his arms – not for sex or power but just to be like him. He was not vain like me. I’m always checking what I look like or thinking about how I appear. He never did. He was himself. I never achieved this. Ho, ho, I’m not dead. So I still can – and I will.”

And she did. She became her fully rounded self as a painter, businesswoman and chatelaine of an enchanting country house.

Surrounded by lazy lotus-eaters in her youth, she reacted against them and hated sloth. I remember her once shouting at some rich cousins in their forties, who overslept till lunchtime at Clandeboye – at how spoilt they were; how they were wasting their life.

Lindy was determined not to waste a second – and she didn’t. Her London housekeeper, Ana Gama, once answered the door early in the morning to find an important business visitor. She rushed upstairs to find Lindy sound asleep, having forgotten the appointment.

Rather than go downstairs and admit to oversleeping, Lindy got dressed, lightning-quick, dashed downstairs and slipped out of the front door, unnoticed, with her unwitting visitor waiting in the sitting room. She then turned around on the doorstep, came rushing back in, slammed the door and ran to her visitor, with profuse apologies – she’d had another meeting that had overrun, she said.

Her allergy to self-indulgence guided her towards charity. When she sold a Lucian Freud picture (Freud had been married to Sheridan’s sister, the writer Caroline Blackwood), she used the proceeds to endow her charitable foundation to help the forest school in the Clandeboye woods.

Not long after, she wrote in her diary: “[I went to the] Lucian Freud show. My little picture is there. It held its own – it was generating all those children in the woods: I find this thrilling. I could have bought a house in Portugal and could be there now but I would not be happy and fulfilled as I feel this morning.”

Even as she launched herself into her charitable life, the memories of her youth kept bouncing back in her diaries.

It was a world she was born into – and stayed connected with all her life – but viewed at one remove. Staying with the Duke of Marlborough (Bert) in 1967, she wrote: “I sat next to Bert at dinner. ‘Hum... 30 housemaids at 5 shillings a week’ was his retort when asked about the servant problem.”

Again and again, she saw through, with her X-ray specs, to the chilled bones of rich men’s souls. In 1974, Aristotle Onassis told Lindy that he wished he’d kept a diary, like her, “to be able to recall incidents which at a later date would be of use in a lawsuit”. Jackie O, by contrast, Lindy wrote in the same entry, “is as thin and breathless, hypnotic and charming as she should be”.

At one point in her diary, she recorded: “A classic conversation about trying to sack a secretary/groom – it was how I was brought up with Gloria [Guinness – her It-girl stepmother] and Daddy and it was fascinating to see how I still resent it and want to talk about plants, thoughts, ideas etc.”

Six weeks before Lindy died, aged 79, from cancer, in 2020, I visited her at Clandeboye. She seemed as lean and fit as ever – and our conversation revolved, as it had done all my life, around “plants, thoughts, ideas etc”.

What a life she led. And what an arc she had completed. As my father writes in the book I have edited in her memory: “She did it all herself. I’ve never met anyone else who was quite as self-made as Lindy. That’s an odd thing to say about someone whose mother was a duke’s daughter and whose father was a Guinness millionaire and who claimed never to have boiled an egg or done the shopping.

“But from the day we met in our late teens until her late seventies, she was always questing and questioning, always eager to learn some new trade or art – painting, dairy farming, property development, golf course design, forestry, stained glass – and to make friends with the best person to teach her.”

How much my dear godmother taught me about how to make the most out of life.

‘The Last Marchioness – A Portrait of Lindy Dufferin’, edited by Harry Mount, is available from Venn Press, £16.99 plus p&p. Email vennorders@gmail.com for orders

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks