The global 100-year catastrophe that still grips our towns and cities

Sensory deprivation is sickening our minds – and the cure is putting more emotion into how we design our buildings, says Thomas Heatherwick. In this second of a three-part serialisation of his new book, ‘Humanise: A Maker’s Guide to Building Our World’, he argues for less glass and more soul

I want to talk about the importance of the outsides of buildings rather than the insides. This isn’t because I believe the insides don’t matter. They matter a lot, but they only matter to the people who go inside the buildings. Also, it’s relatively easy to change how the interiors of buildings feel, with paint and objects and furniture. The outsides of buildings are different. They matter to everyone who goes past them. And that’s a lot more people. But most of us are truly powerless to change how these outsides make us feel.

For every individual person that spends time inside an office or block of flats, there will be hundreds or even thousands of people that pass by the outside of that building every day. The outside of that building will affect every single one of those people. It will contribute to how they feel.

As they walk down the street, and they pass by dozens of buildings, they’ll feel dozens of emotions.

And those emotions add up.

Those emotions matter.

They matter more than we realise.

Over the last hundred years or so, the outsides of the ordinary buildings we pass by every day have taken on a certain “look”. It’s present in towns and cities all over the world.

This look has turned out to be astonishingly harmful. The places that have been built for us, that have adopted this look, make us stressed, sick, lonely and scared. They’ve contributed to division, war and the climate crisis.

This look we stumbled upon a century ago has been a global catastrophe.

There’s a word that describes the kinds of buildings I’m talking about.

I don’t like this word. It’s bland, vague and forgettable. It seems unserious.

This word doesn’t do justice to the harm it describes. It fails to capture the intense and dreadful changes that have been creeping through our towns and cities for the last 100 years, bringing with them destruction, misery, alienation, sickness and violence.

I wish there was a better word I could use – one that, when you heard it, gave you a truly visceral sense of what I’m convinced is a century-long global catastrophe we’re still in the grip of.

But when I think about this catastrophe, and I think about these buildings, I always come back to this word.

So here it is.

Boring.

I did warn you.

When you hear the word ‘boring’, you almost certainly think: ‘A whole book about the boringness of buildings... really? We have so many problems in the world: social injustice, the climate crisis, political polarisation, war, tyranny and corruption. And you’re making a big song and dance about... boring buildings?!’

And then you might quite reasonably think: ‘Who the hell are you to call something boring anyway? Just because you don’t like this shopping centre or that office block, it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s bad.’

If you are thinking these things – well, I don’t blame you. If I were you, I’d probably be thinking them too. I can only ask you to hold on, for just a few more pages.

There are some serious issues to consider that affect billions of people.

By the end of this essay, I hope to have convinced you that we’re under attack from a plague of boringness, and that it really is a global catastrophe.

What does boring actually mean?

Too flat

The fronts of modern buildings tend to be incredibly flat.

Their windows and doors barely stick in or out.

Their roofs are often flat too.

The lumps and bumps in buildings matter because they create interest. In countless subtle and intricate ways, a building with depth changes its appearance with the movements of the sun – a patch of brightness here, a nook of darkness there – the light flowing in and out of doorways and window frames as the Earth turns through the day.

When buildings are too flat, they are punishingly boring.

Too plain

Modern buildings lack ornamentation.

When you look at buildings that were constructed more than a century ago, it’s striking how much care their designers took to add flourishes of complexity.

These buildings have patterns, details and decorations.

They have lumps and bumps and crevasses and curls and crenellations and cornices and points that stick up and out and in and around. Even everyday buildings that weren’t thought of as “special” or “important” were made with this mindset – with an interest in interestingness and what was thought of as beauty at the time.

When buildings are too plain, they are boring.

Too straight

Modern building design tends to be based on rectangles. There’s nothing inherently wrong with this approach (classical buildings were the same), and it makes a kind of logical sense because it’s highly practical. It’s also much easier to design things with straight lines and right angles – even more so with the latest building design software that most easily draws squarish shapes.

But the exclusive use of straight lines and rectangular geometry has got wildly out of hand. When used on buildings at scale and in the absence of any other kind of shape, they tend to create scenes of repetitive horizontality, and feel hard and utterly unfriendly to walk past. They are inhospitable to human beings. Given that there are virtually no straight lines or right angles in nature, they are also astonishingly unnatural.

Too shiny

The outsides of modern buildings tend to be made from smooth, flat materials such as metal and glass. Shiny materials can be lovely, but when entire buildings – and even entire districts – are made from only hard-feeling reflective materials, our senses become numb with indifference. This lack of variety has a profoundly desensitising effect.

New buildings often have large pieces of relatively thin glass clipped together in place of solid walls with windows. Even when they also have large areas of metal panelling, the surfaces of all of those materials still tend to be uniformly smooth and flat, which provides nothing for our senses to latch on to.

The most extreme example of this is the construction industry’s invention of curtain wall glazing – by which the entire outsides of buildings can be made of nothing but huge sheets of glass. When this is used, any human interest and variety that the outsides of buildings could have is virtually killed.

When buildings are too shiny, they are boring.

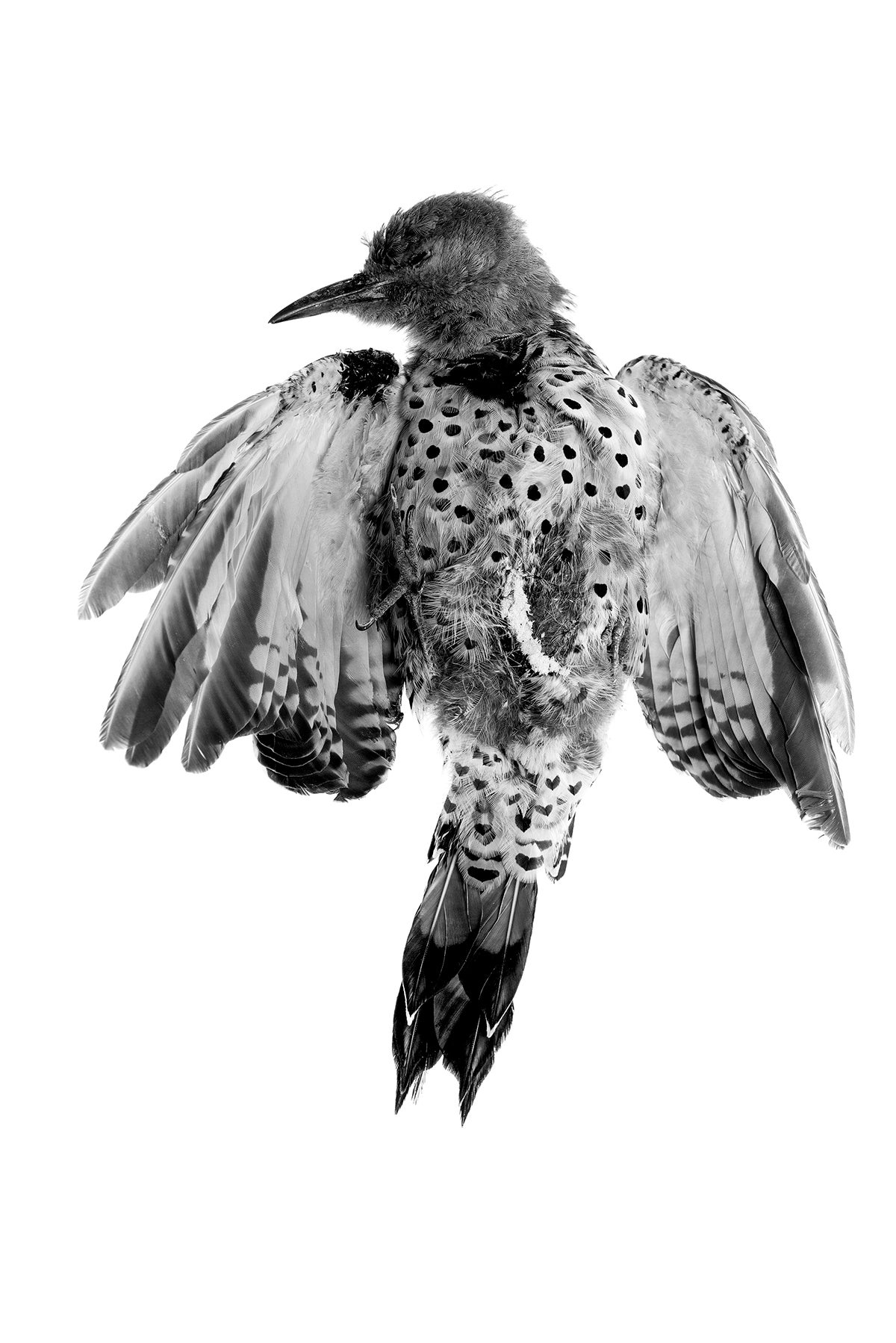

The increase in glass on buildings has also contributed to mass bird slaughter. It’s been estimated that, in the US alone, between 100 million and 1 billion birds die every single year as a result of flying into windows.

Too monotonous

Modern buildings often take the form of rectangles that are made up of smaller rectangles. These rectangles are arranged in a grid.

If a straight street is lined with these grid-like buildings, the landscape becomes a repetitive queue of large, flat, shiny, plain rectangles.

These buildings look monotonous from a distance.

And they look monotonous from up close.

This kind of monotony doesn’t inspire or excite or fascinate human beings.

Too anonymous

More than 100 years ago, the outsides of buildings tended to capture something of their place; they were, in some sense, articulate. They told a story about where they were, and who they were for. Today, they mostly don’t.

This 100-year catastrophe has been a cultural revolution. It’s ruthlessly stripped new buildings of their personality and sense of place.

When buildings are too anonymous, they are boring.

Too serious

When you look at these kinds of office buildings, what do you feel?

You feel serious, perhaps even a little intimidated. These are serious buildings for serious people, in which serious lives are being lived. Why do buildings need to look serious? Why were their creators so scared of making somewhere that makes people feel joyful? These sorts of buildings are only capable of evoking one kind of feeling. They suffer from an extreme case of emotional austerity.

When buildings are too serious, they are boring.

When is boring boring?

In the right contexts, and with the right intentions, the base elements of boring can be wonderful. But when too many of these elements come together into one building or one place, boringness becomes a serious problem.

The way I see it, boring is like an equation.

It’s like putting too much sugar, fat, carbohydrate, alcohol and nicotine into a human body. More often than not, it’s the combination and accumulation over a lifetime that kills you.

When too much boring happens in one space, it becomes... harmful boring.

How can boring be harmful? Isn’t boring an absence, a pause, a piece of nothing? Nothing can’t harm you. Nothing is nothing, after all.

But the astonishing and little-known truth is that boring is worse than nothing.

A lot worse.

Boring is a state of psychological deprivation. Just as the body will suffer when it’s deprived of food, the brain begins to suffer when it’s deprived of sensory information.

Boredom is the starvation of the mind.

A neuroscientist called Colin Ellard has studied how this happens. In 2012, he travelled to New York City to analyse how people felt when they walked through a boring place and then, shortly afterwards, through an interesting place. He wanted to know: how would spending just a brief amount of time in these different places affect a person’s mood?

This was the boring place. It’s the outside of a Whole Foods, a large supermarket on New York’s Lower East Side. It takes up an entire block.

This was the interesting place, just a short walk away from the Whole Foods Market.

As the groups walked through each location, a specially designed smartphone app asked them questions about what they were seeing and how they were feeling. Outside the supermarket, the most common responses included: bland, monotonous and passionless. However, down the block from Whole Foods, the most common responses included: socialising, busy and lively.

But the truth is Ellard didn’t need an app to identify how their moods were being altered. It was obvious. ‘In front of the blank façade, people were quiet, stooped and passive,’ he wrote in his account of the study. ‘At the livelier site, they were animated and chatty, and we had some difficulty reining in their enthusiasm.’ One rule of the study stipulated that participants shouldn’t talk to each other. At the Whole Foods Market, maintaining silence wasn’t a problem. But at the interesting location, the researchers lost control of their subjects. The rule of silence “quickly went by the wayside. Many expressed a desire to leave the tour and simply join in the fun of the place.’

Ellard was also collecting data on the participants’ emotional states, from special bracelets that took regular readings from their skin. These bracelets were detecting a state that scientists call ‘autonomic arousal’.

Autonomic arousal refers to how alert we are, and how primed we are to respond to threat. It’s a measure of stress.

When Ellard checked the results, he discovered that people in the boring location weren’t simply feeling nothing. Their autonomic arousal – their stress levels – had gone up.

The boredom wasn’t just making them feel nothing. Their brains and bodies were going into a state of stress.

You can imagine why being chased by a predator or being locked up in prison might start to stress you out. But why would a boring place make you stressed?

Scientists have found that when we enter any environment, we unconsciously scan it for information. During the millions of years in which our brains were being moulded by evolution, we lived in nature. And natural environments are crammed with complexity. Every single second, our senses deliver around 11 million pieces of information about our environment and surroundings to our brain. The human brain has evolved to expect this base level of information, a bit like the body expects base levels of oxygen, water and food.

Boring modern landscapes, which privilege repetition over complexity, supply us with an unnaturally low level of information. Ellard theorises that walking through them is a bit like having a phone conversation, but you’re only hearing words like ‘it’ and ’so’ and ‘the’. There’s some information there, but it’s repetitious, non-complex and of extremely low quality.

When the brain is deprived of information from its environment, it takes it as a signal that something is wrong. It panics. It switches the body to a state of alert, raising its readiness to deal with danger.

More than 100 years ago, it would have been extremely hard to find a truly boring external urban environment. Today, boring environments are everywhere. We’re blanketed in boringness.

-------------

As you read these words, there are professionals in studios drawing flat, plain, shiny, anonymous, serious rectangles and squares, and declaring them to be elegant, honest, visionary and stunning.

Concrete is being poured.

Cranes are lifting huge flat panes of glass into place.

Boring buildings are going up in towns and cities all across the globe.

Currently, more than half of the Earth’s population lives in an urban area. By 2050 that number is expected to rise to over 70 per cent.

A world of harmful boring is being built for us to live in, whether we like it or not.

Read part one of our exclusive serialisation here: ‘Gaudí’s Casa Milà is a joyous festival of curves – it’s almost as if the building is breathing’

TOMORROW: How to make truly human buildings – the concluding part of our serialisation

Extracted from ‘Humanise: A Maker’s Guide to Building Our World’ by Thomas Heatherwick, published by Viking on 19 October at £15.99. © Thomas Heatherwick 2023

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

66Comments