‘Just like the film American Fiction, my books have to speak to my ‘African heritage’ to get noticed’

Writer Chioma Okereke was taught by the novelist whose book inspired the Oscar-nominated film ‘American Fiction’. Like the movie’s frustrated protagonist, her own experiences are the same: when you are Black and African, there is often only one kind of story publishers seem to want from you...

With the success of Percival Everett’s 2001 novel Erasure coming to the big screen in the form of the five-times Oscar-nominated movie American Fiction, the question of what an authentic Black experience is has never been more in the spotlight.

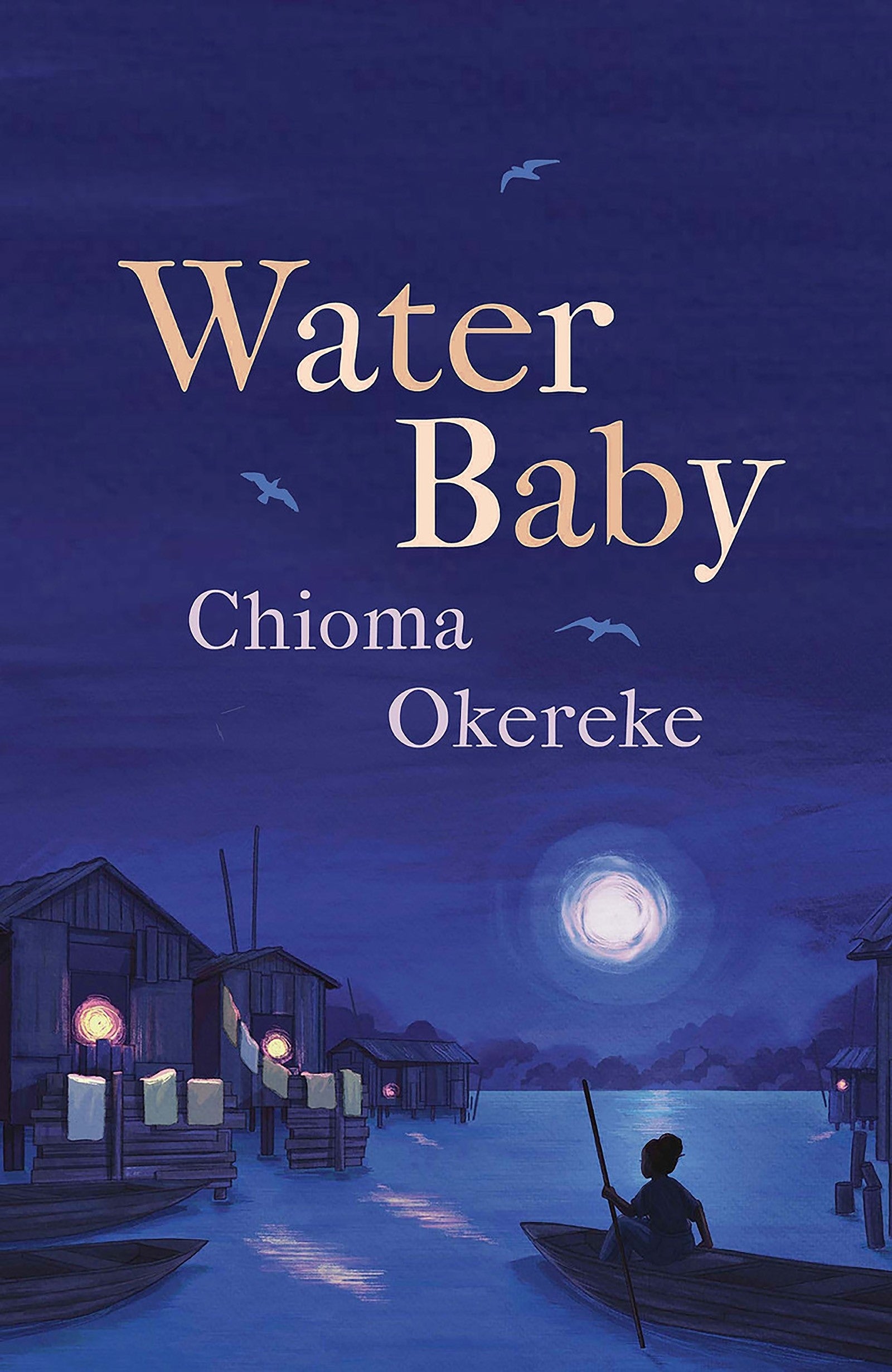

My upcoming novel Water Baby is a coming-of-age tale portraying the societal pressures on a young woman trying to escape the confines of her community. It’s set in Nigeria – where I was born – but it could have easily been Hertfordshire and London where I grew up, or rural France where I’m living now.

What makes me an African author isn’t my location, but my essence – my DNA, my cultural experiences, how I perceive the world. But it often feels as though African authors like me are compelled to be cultural historians or commentators in order to be published in the traditional way.

My latest novel focuses on people from Makoko, the informal settlement over water in Lagos, Nigeria; the world’s largest floating slum. But I only visited it after penning my first draft; I’m not part of that community, although spending my early years in Nigeria and my trips back undoubtedly helped with my storytelling.

I’ve had to be responsible for capturing a real-life community respectfully and representing them truthfully. I needed to also skate between the appropriation versus appreciation lines. I needed to be aware of the outside gaze – mine included – as well as my privilege when approaching my work of fiction.

I was delighted, like any author would be, when it sparked publisher interest and got me a deal, but like Thelonious “Monk” Ellison, the protagonist in American Fiction, I can’t help questioning why the pieces of my work that have found recent success were selected for it.

I first met Percival, author of Erasure, the book American Fiction is based upon, at the ICA in 2003. He was giving a talk and I was a fledgling author, moving from a life as a poet and starting to get to grips with prose. Artists often talk of that one person who gave their initial validation. For me, Percival was exactly that. I approached him at the end of his talk, spoke about my writing, and he offered to read a sample.

A few weeks later he replied, telling me that he liked it and in the same email, invited me to attend the Callaloo writer’s workshop at Texas A&M University the following May. To the 2004 class of fiction students, he became affectionately known as Percy Love – but that’s a story for another day.

In the novel and now the film, Monk is an African American author and professor whose recent works are rejected for not being Black enough. Frustrated by the industry’s stereotypical expectations, he pens a parody embodying every African American trope and cliché the industry appears to crave. He does this under a pseudonym and the book becomes a mega sensation.

The pivotal scene in the movie where Monk decides to create Stagg R Leigh echoes my own thought process when it came to writing my new book, which is out in April.

I’d just received a rejection of another book – set in rural France, where I currently reside. Publishing rejections are occasionally very detailed, but mostly not, and this was one of those confusing “we really enjoyed it but can’t quite put our finger on why it’s a no”. I consoled myself by finding a programme to watch on YouTube and stumbled upon an episode of The Best Ever Food Review Show, shot in Makoko.

I’ve been to Lagos many times to visit my father, but I’d only ever seen the community through a car window when crossing the bridge to get to Victoria Island. There’s a painting in his living room, depicting a hut in Makoko that I must have seen a hundred times, but this place had never come to life to me before in the way it did during that show.

While I’m an African writer in possession of an African name, I lead a global, trans-ethnic existence, and for whatever reason this detail misses the mark in terms of what the industry deems to be my primary appeal

As my mind wandered to a food scene, a picture of a young woman flashed in my brain. I saw her face vividly, the silhouette of her frame as she steered a canoe through the dark water of the Lagos lagoon. I quipped flippantly to my other half that if I were to write a book about this girl – rattling off a trope-filled plotline – it would be snapped up instantly. Of course, he challenged me to do it, so I got to work.

But as I began my research into the community and the flesh began forming around the bones of my protagonist, I couldn’t bring myself to write a stereotype-heavy tale that I’d planned. Just like my protagonist in Water Baby – Yemoja/Baby – who wants to do things her own way, I wanted to find my way of telling a story in the unique and unfamiliar setting to most, but without leaning on all the usual tickbox stereotypes found in other novels that suggest that the African experience is monolithic.

For both my published books, I’ve steered carefully around editorial discussions with industry professionals to find the balance between what could genuinely make a draft better and issues that I’m uncomfortable with. This includes racial stereotyping, lazy poverty tropes and unnecessary abuse and violence; adverse as I am to in any way contributing to what effectively constitutes trauma porn.

The praise that I’m now receiving for Water Baby is, of course, most welcome. It is a book that raises wider issues including climate change, digitalisation, gentrification, and resettlement, while exploring the human condition from a perspective that often goes unnoticed. I’m proud of the novel and hope the research resulted in a story that provokes thought and elicits emotion.

But, for me, it’s no coincidence that the two pieces of my work that have captured the interest of the publishing industry the most have been the ones set in Africa; the ones that hinge onto my Nigerian name, as if readers are unable to imagine any other type of storyline or setting from a writer whose name correlates with their ethnicity. That’s insanity and I say this as a writer who’s a reader first.

The cynic in me finds it hard to believe that my best work is from the country I’ve spent the least amount of time in, in comparison with France and the UK, where I’ve clocked in more miles and experiences. I don’t believe these tales are fundamentally better than my stories set elsewhere so is it down to a perception of me as an African writer that I’m unable to shake?

If I were labelling myself, I would say that while I’m an African writer in possession of an African name, I lead a global, trans-ethnic existence, and for whatever reason this detail misses the mark in terms of what the industry deems to be my primary appeal.

Me writing about my birth country curiously resonates. I find the authenticity of my work is automatically granted – by virtue of my name correlating to my nationality – puzzling, and the industry a familiar jigsaw; slow to embrace the full breadth of experiences associated with Black, and most certainly with African, identity.

‘Water Baby’ by Chioma Okereke will be published by Quercus on 11 April in hardback, ebook and audiobook

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments