I’m a psychologist, and this is the truth about whether you can tell if someone is a ‘psychopath’ or not

These character sketches of people with 'personality disorders', so influenced by the mores and gendered norms of what is acceptable at any given time, are not backed up by any scientific evidence

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Everyone appears to be diagnosing everyone else with a personality disorder these days. From accusations Trump has narcissistic personality disorder or is a "dangerous psychopath", and the Twitterati has gone mad for a series of MailOnline articles detailing “How to tell if your lover, boss of friend is a PSYCHOPATH” this week. Writing about personality disorders clearly gets people reading. But do they actually exist? Or is this move just another way of hating on one another in an increasingly contempt-ridden society?

People tend to associate personality disorders with certain celebrities and movies. In the 1980s, Glenn Close’s character in Fatal Attraction was storied as having “borderline personality disorder” (BPD). She was seen as the ultimate femme fatale, a slave to her sexual passions and murderous impulses and a danger to men and marriage in contrast to Anne Archer’s loyal, betrayed and terribly dull wife.

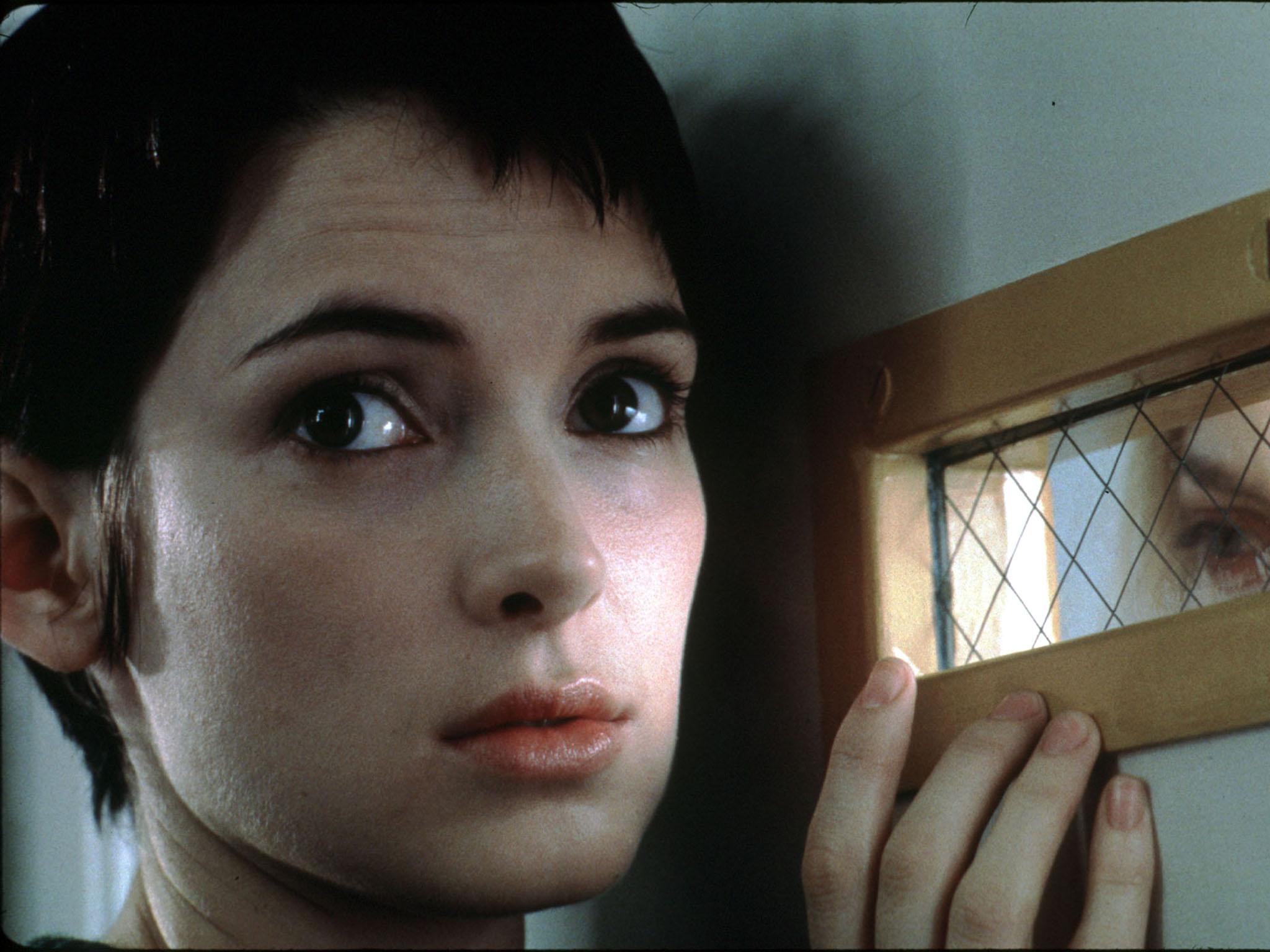

In the 90s, Winona Ryder’s character in Girl Interrupted bought the idea to a whole new audience. Throughout subsequent decades, up until today, numerous celebrities who have not fitted contemporary ideas of how women should behave have been slurred with the idea that they might have BPD. These include Princess Diana, Angelina Jolie and Amber Heard – all dazzling, daring women that the public cannot quite reckon with.

In recent years, there has been increasing interest in the idea of narcissism and “narcissistic personality disorder”. BPD is a diagnostic category populated overwhelmingly by women, narcissism more with masculinity. Just as women with a diagnosis of BPD are characterised as having a reckless relationship with emotions they could or should be able to control, men with narcissistic traits are seen both in the public imagination and psychiatric nosology as too self-centred, too lacking in empathy, too obsessed with conquer at all costs. These character sketches, so influenced by the mores and gendered norms of what is acceptable at any given time, are not backed up by any scientific evidence. They seem immune to our newfound capacity to celebrate difference, and look to the back-story behind any given personality. They derive from a time when personalities were more stable because people’s lives were more closely tied to the social bonds of a given local community, and when conformity was privileged.

Modern ideas of the "protean" self who can explore, play and self-create are absent from the discourse of personality disorders, despite consistent evidence that all our personalities are a work in progress, shifting form across adulthood. Enter most personality disorder services as a patient today and one would think one has an affliction for life, despite robust evidence that more than 50 per cent of people diagnosed with BPD, for example, no longer meet the criteria after five years. Being super messed up and at times destructive for a few years is a passing stage for many of us in early adulthood. To have this stage rubber-stamped with the words “personality disorder” can be incredibly traumatising, keeping one entombed in the worse period of one's life.

There are signs things are changing, though sensationalist “pathologise your partner/president” articles suggest the exact opposite. While there are construct problems with the majority of psychiatric diagnoses, the difficulties with personality disorders are of another magnitude (hence the “mad or bad” debate that has dogged the field forever). Even the “what about Trump?” defence holds no water, for the idea of narcissistic personality disorder would not stand up to two minutes of serious scrutiny in a courtroom.

Accordingly, all the subtypes of “personality disorder” will pretty much definitely be dumped in the forthcoming version of the ICD – the diagnostic bible we use in Europe. The likely revision is an improvement, but one still deeply tainted by cultural norms such as the idea we should have loads of friends, be socially embedded, and be employed. This is dangerous for being bombarded by these kinds of norms, which do not fit for everyone, and would cookie-cutter us, are often a source of the pain, shame and suffering which result in presentation to psychiatric services in the first place.

We need to recognise that the idea of “personality disorders” is one that can distract us from the real questions that we need to ask to understand why someone is suffering, and what we can do to help. Why is someone struggling to fit in? What does that say about our society, and our ideas of what men and women are supposed to be like? What is emotional turmoil a consequence of? Why are relationships difficult, and what early experiences have set up such damaging ways of relating? What is the story behind the surface?

For an overwhelming majority of patients, the difficulties which are labelled as “personality disorders” are a result of trauma. These traumas may be glaringly obvious ones such as childhood sexual abuse or bullying, or less immediately evident experiences such as having been raised in an environment where one was expected to live out the dreams and aspirations of a parent, or manage the emotional temperature of a family at the expense of developing one’s own separate pathway and secure sense of self. Such traumas are supercharged by wider societal factors such as poverty and misogyny, and indeed the invalidating response of psychiatric services which make people feel like they are a “bad apple” after all.

Many patients report that the moment their diagnosis changes from “personality disorder” to another diagnosis, they experience an entirely new response from mental health services. Rather than being viewed as “difficult”, “attention-seeking” and “manipulative”, they are listened to, empathised with and helped. Labelling each other with borderline, narcissistic or schizotypal “personality disorders” and diagnosing public figures in the media may feel like casual fun, but it reinforces ideas which have cost many of the most amazing people their lives throughout history and up until today.

Let’s reject the ideology of “personality disorder” and, instead further cultivate a culture that celebrates difference, and that proffers frameworks of understanding significant distress that do not redouble trauma.

Jay Watts is a clinical psychologist and psychotherapist

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments