‘The people are on the move... they want a change, not of rules but of regime’

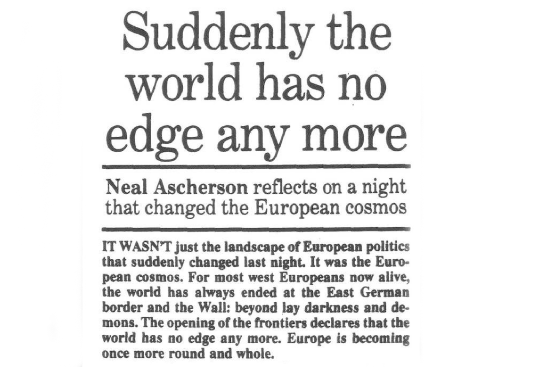

On the fall of the Berlin Wall

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.10 November 1989

It wasn’t just the landscape of European politics that suddenly changed last night. It was the European cosmos. For most west European now alive, the world has always ended at the East German border and the Wall: beyond lay darkness and demons. The opening of the frontiers declares that the world has no edge any more. Europe is becoming once more round and whole.

This is the best news the German people have heard since 1945. But it’s right to look back: at the huge, artfully built frontiers of wire and lights, towers and minefields, dogs tethered to wires, sensor devices and mantrap guns, sanded death strips, helmeted men with guns. There, on the border of the Berlin Wall, hundreds of human beings died and hundreds were horribly maimed. The dogs howled and raved in the night. Sometimes there would be detonations, and then the screaming which might be human or might be a roe deer blown in half by a mine. That is what is now over.

When the Berlin Wall was built in 1961, the East Germans claimed that by sealing the Berlin border they had saved the peace. Then as now, the outrush of people to the West was threatening to bring about the collapse of the East German state, but in an utterly different world. It was the world of Nikita Khrushchev, and that collapse would have brought the two superpowers into violent collision. Now that reasoning sounds like a bad dream. It’s by opening the borders, not by closing them, that the East German regime tries to avert collapse. And the man in the Kremlin is Mikhail Gorbachev, not the man who screamed at capitalism: “We will bury you.”

But, of course, the East German leaders are still playing games here. Their move is both desperate and shrewd. Egon Krenz can live with two possible results of what he has now done. The first possible result is a colossal bolt to the West, which would make the inrush of the last months just a prelude. If that happens, the Bonn government is trapped. West Germany cannot assimilate a far greater inflow. Instead, Bonn would be driven to provide the enormous economic assistance and political encouragement – to make it a country worth staying in. It would mean, in effect, committing West Germany to Mr Krenz and his version of reforms. And that Mr Krenz well knows.

The other outcome could be that the population, seeing one of its biggest grievances met, will begin to simmer down. There would be a temporary increase of emigration to the West but then the torrent would dry to a manageable trickle. This, too, would be most agreeable for Mr Krenz.

It’s certainly true that many of these refugees … would return home if their country were more free and its borders remained open. Heimat has a far deeper pull on the Germans than on the British. The trouble here is about freedom. Mr Krenz is gambling that his subjects will now go home and start planning foreign holidays. But the people are on the move – the biggest spontaneous movement of Germans since the 1918 revolution. They want a change, not of rules but of regime.

For the moment, the Wall and the wire stand. But poets often see farther than politicians. Hans-Magnus Enzensberger, in a book published last month in London, predicts the Berlin Wall as a picturesque relic running through a reunited city. Its remains would be coveted by developers but fiercely defended by ecologists and heritage buffs. And sure enough, last night the physical divisions of Germany began to turn into history.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments