Bill Bryson’s America

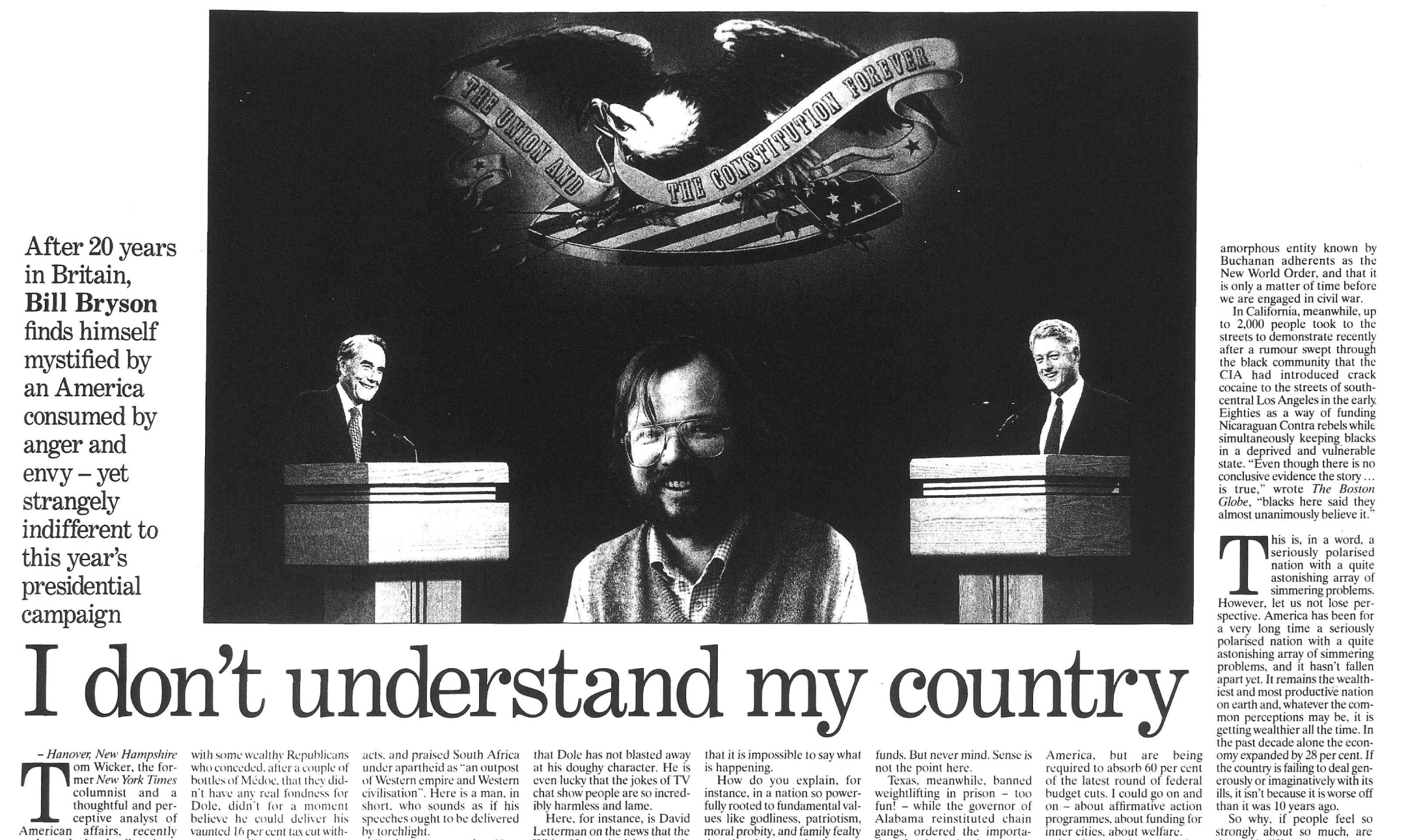

A perplexed columnist reflected upon the contest between Bill Clinton and his Republican challenger Bob Dole

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.22 October 1996

Tom Wicker, the former New York Times columnist and a thoughtful and perceptive analyst of American affairs, recently spoke at the local college here and I went along to hear him. I went because I had been asked to divine the mood of the electorate, and I was hoping to appropriate some of his thoughts on the matter, not having found any myself.

Wicker has been closely watching American elections for more than half a century and he said that he had never seen one quite as irrelevant, quite as inattentive to the real issues, as this one.

He was, of course, quite right. You would scarcely guess from this election campaign that America has some serious problems – indeed, pretty much leads the developed world – with regard to issues of race, violent crime, homelessness, economic disparities, imprisonment, illiteracy, health care, low savings rates, and a great deal else.

Wicker talked a little about several of these matters, but didn’t really touch on anything you could call a mood. He appeared to be a Clinton man, but listlessly.

That same night I had dinner with some wealthy Republicans who conceded, after a couple of bottles of Medoc, that they didn’t have any real fondness for Dole, didn’t for a moment believe he could deliver his vaunted 16 per cent tax cut without unsettling the economy, and didn’t for a moment think he did either. They would vote for him, but listlessly.

And so it has been nearly everywhere. If there is an American out there with anything approaching a strong feeling about either candidate, I have yet to find him. Even Bob Dole, who has the pleasingly disconcerting habit of referring to himself in the third person, as if he isn’t actually there, often seems as if, well, he isn’t actually there. It is striking that the longer the campaign goes on without any kind of hopeful signs for Dole, the happier he looks.

This is not perhaps such a bad thing. The election campaign could have been more interesting, to be sure, but it also could have been a lot more scary. To begin with, the Republican nominee could very well have been Pat Buchanan – a man who, let us never forget, once described Adolf Hitler as “an individual of great courage and extraordinary gifts”, characterised Aids as a form of natural retribution for unnatural acts, and praised South Africa under apartheid as “an outpost of Western empire and Western civilisation”. Here is a man, in short, who sounds as if his speeches ought to be delivered by torchlight.

Buchanan won the New Hampshire primary. He could easily have gone all the way. If Bob Dole does nothing else – and often in this campaign, that has appeared to be his strategy – he has saved his party and the rest of the world from the unnerving prospect of Pat Buchanan as the Republican nominee for president.

All of this is good news for the irrepressible Bill Clinton. What an extraordinary politician. This is a man among whose lesser problems – his lesser problems – is that he stands accused of having deprived one Paula Jones of her civil rights by asking her for oral sex in a Little Rock hotel room in 1991.

Surely there has never been a luckier man. He is lucky that the American media don’t know what to do – are literally paralysed with uncertainty – when the words “President of the United States” and “genitalia” threaten to find some sort of natural proximity. He is lucky with the economy, which is positively rosy. He is lucky beyond belief that Dole has not blasted away at his doughy character. He is even lucky that the jokes of TV chat show people are so incredibly harmless and lame.

Here, for instance, is David Letterman on the news that the White House had improperly examined FBI files on 340 people: “They’re saying the whole thing is a mistake. They say... it was a typographical error. Clinton was not ordering more files, Clinton was ordering more fries.”

And here is Jay Leno on Clinton’s position on homosexual marriages: “Clinton’s really confused on this issue. See, he thinks that same-sex marriage is having sex with the same partner you’re married to.”

(Oh, stop, you guys. My sides are aching.)

If it is not easy to discern any kind of mood in America at the moment, it isn’t because people haven’t been looking. The nation abounds with books with titles like Middle Class Dreams: The Politics and Power of the New American Majority and The Inheritance: How Three Families and America Moved from Roosevelt to Reagan and Beyond. This latter devotes 464 pages – the scale of, say, a Mario Puzo novel – to examining how three anonymous and, it would seem, totally uninteresting people abandoned their Democratic roots and became conservatives.

Most of these books are dull, weighty, and dreadfully earnest, and they sell in vast numbers. What is notable about them is that nearly all were begun at a time when Newt Gingrich, the House speaker, was the most popular politician in the United States and published at a time when he has become the most despised – a remarkable turnaround foreseen by no one. The fact is that politics in America are so wildly erratic these days that it is impossible to say what is happening.

How do you explain, for instance, in a nation so powerfully rooted to fundamental values like godliness, patriotism, moral probity, and family fealty that the electorate is about to reject a solid, conservative, war- hero Republican in favour of a slick Democrat with a roving eye and elastic scruples?

No wonder people are confused. And, as often with confused people, they are angry. Americans are angry about everything and nothing. I have never known a period of such peevishness in my native land. Resentment has become the guiding sentiment for millions, “zero tolerance” the watchword. If there is the slightest chance that anyone anywhere has enjoyed a privilege not enjoyed or appreciated by, say, a factory worker in Skokie, Illinois, you can be sure that that privilege has recently been revoked.

Consider the matter of Pell grants. For years, these little-known disbursements enabled prisoners to acquire a college education. Although it has been shown that such programmes cut recidivism rates to about 13 per cent (against about 60 per cent for non-educated prisoners), and although prisoners accounted for only $35m of the $6bn total cost of the Pell programme, Congress stopped it last year after Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison of Texas complained that “honest and hardworking people are being elbowed out by criminals”.

In fact, because Pell is an entitlement programme – that is, one that provides grants to all eligible applicants, not only the most deserving – no one, whether prisoner or free, had ever been denied Pell grant funds. But never mind. Sense is not the point here.

Texas, meanwhile, banned weightlifting in prison – too fun! – while the governor of Alabama reinstituted chain gangs, ordered the importation of rocks to give them something to hammer away at, and sent bulldozers to plough up prisoners’ vegetable gardens.

Or consider drugs. The minimum mandatory federal sentence for possession of a single tab of LSD is now 10 years. Never mind that perhaps you didn’t even know it was LSD, that a stranger thrust it upon you when he saw the police coming through the window. Never mind that you are 19 years old, of previous good character and that this will ruin your life. There are no excuses. We are zero tolerant.

Consider immigrants. In 1994, Californians voted overwhelmingly for a bill called Proposition 187, designed to deny health and education services to illegal immigrants and their children. Governor Pete Wilson, the man behind the proposition (and who, according to The Los Angeles Times, may once have employed an illegal immigrant maid himself), immediately directed state health authorities to stop providing pre-natal care to illegal immigrants – in effect, told undocumented immigrant women to go and have their babies on park benches. (The proposition has since been stalled in the courts.)

In the second Presidential debate, Bob Dole said, “This is America. No one is going to go without food or health care.” Actually that is not so. President Clinton just last month signed a bill denying Medicaid benefits even to legal immigrants.

Consider the poor, who receive only 12 per cent of total discretionary spending in America, but are being required to absorb 60 per cent of the latest round of federal budget cuts. I could go on and on – about affirmative action programmes, about funding for inner cities, about welfare.

I can’t pretend to guess what goes on in people’s heads these days – whether they think the less privileged have been given an unfair leg-up and that it’s time to level the playing field, whether they are so angry that they simply want somebody else to suffer for a while, whether they think these changes will really bring solutions rather than just much greater problems later.

One factor that makes this scatter-gun hostility more interesting, more perplexing, and indubitably more American is that it is frequently accompanied by a large dose of paranoia. People have taken to seeing conspiracies in almost everything. In Tennessee, for instance, religious fundamentalists are endeavouring to give the teaching of creationism equal standing with the teaching of evolution in state schools (proving yet again that the danger for Tennesseans is not so much that they may be descended from apes as overtaken by them).

The striking thing about the debate there is that most creationists don’t merely believe that the evolutionists are wrong, the victims of a sincere but misguided attachment to Darwinian theory, but that they are engaged in a manipulative, large-scale, carefully orchestrated campaign to subvert the word of God. It is not enough, you see, that your opponents might disagree with you. They must be out to get you. All over the country there are well-armed groups of survivalists who have no doubt that the United States government has become the tool of a sinister but amorphous entity known by Buchanan adherents as the New World Order, and that it is only a matter of time before we are engaged in civil war.

In California, meanwhile, up to 2,000 people took to the streets to demonstrate recently after a rumour swept through the black community that the CIA had introduced crack cocaine to the streets of south-central Los Angeles in the early Eighties as a way of funding Nicaraguan Contra rebels while simultaneously keeping blacks in a deprived and vulnerable state. “Even though there is no conclusive evidence the story ... is true,” wrote The Boston Globe, “blacks here said they almost unanimously believe it.”

This is, in a word, a seriously polarised nation with a quite astonishing array of simmering problems. However, let us not lose perspective. America has been for a very long time a seriously polarised nation with a quite astonishing array of simmering problems, and it hasn’t fallen apart yet. It remains the wealthiest and most productive nation on earth and, whatever the common perceptions may be, it is getting wealthier all the time. In the past decade alone the economy expanded by 28 per cent. If the country is failing to deal generously or imaginatively with its ills, it isn’t because it is worse off than it was 10 years ago.

So why, if people feel so strongly about so much, are they so indifferent to the campaign? I wish I could tell you. This is my first election in 20 years, and things have changed beyond my ability to understand them. When I left America in the Seventies, the country was just emerging from a lively and impassioned decade. Campuses were full of hippies: often they demonstrated. The war in Vietnam, civil rights, Kent State, Watergate – all these were still in the air. There was a sense of being on the edge of a period of momentous change.

All that has vanished. Now, even at an elite eastern university such as Dartmouth, here in Hanover, the students nearly all look as if they’re on their way to an Osmonds concert and seem unconcerned by thoughts of a wider, more troubled world. It is as if the nation’s problems have plodded inexorably onwards while the inhabitants have scampered backwards towards a safer, simpler age.

That’s one thing you have to like about Bill Clinton. He appears to be almost the only person in America who is genuinely looking forward to the new millennium.

And here’s an interesting consideration. Assuming Clinton wins, it will be the first time in his career that he will not be thinking about re-election. Since he cannot stand again, it is entirely probable that his thoughts will turn to posterity. A Bill Clinton who is able to focus his abundant energies and intelligence on his legacy rather than his next campaign might just be an impressive sight. It will certainly be worth watching.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments