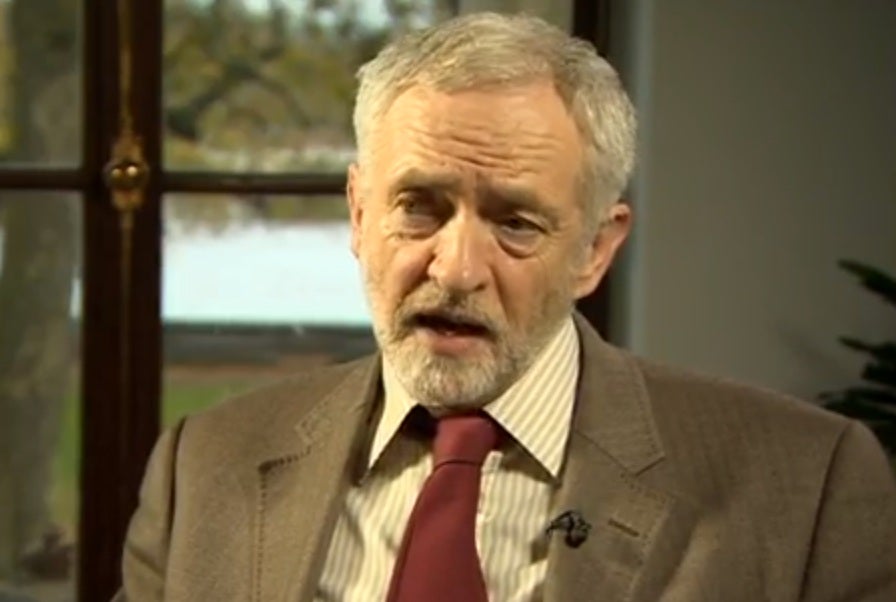

I say this with regret, but Corbyn looks detached over terrorism

A politician devoid of visceral revulsion represents himself as something other than rest of us

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In dismal days such as these, because it is their business to reflect the public craving for simplistic answers to probably unanswerable questions, intelligent politicians say stupid things knowing them to be stupid.

Francois Hollande has declared war on Isis – an absurd reprise of George W Bush’s war against terrrrurh, and no doubt precisely what Isis wanted him to do. Since technically war can only be declared against a country, he has effectively recognised (if not legitimised) its “caliphate” as a de facto sovereign state.

Here, in anticipation of a similar outrage on British soil, David Cameron summoned the old Blitz spirit. He too has aggrandised Isis by deliberately raising the spectre of the Nazis, and conflating the menace of sporadic terrorism, however uniquely brutal, with an existential threat to British democracy. He said it calculating that raising it to the status of the Third Reich will help him win a Commons vote on a bombing campaign in Syria – though one fears he will need little help with that now.

Just as the US response to 9/11 seemed directly lifted from Osama Bin Laden’s bucket list, the leaders of France and Britain appear determined to play into Isis’ hands. Yet however counterproductive you may expect a heightened bombing campaign to prove, you can at least understand the political pressures that compel them to say and do foolish things in times such as these.

What very few will understand is Jeremy Corbyn’s response to the events in Paris. I write this with searing regret, because one of the qualities I have admired about him is his refusal to play dumb. He will not spout fatuous gibberish in populism’s cause, or be bullied into parroting nonsense by the confected hysteria of right-wing tabloids. He remains true to himself and the ideals he has held for half a century, which is splendid. It is even a touch heroic.

Yet there is a borderline between rigorous authenticity and damaging self-caricature. If last week’s ruminations on the execution by drone of Jihadi John took him to its edge, Corbyn strode across it this week when asked if, as Prime Minister, he would operate a shoot-to-kill policy should the nightmare of Paris come to London. The answer is excruciating to quote.

“I’m not happy with the shoot-to-kill policy in general,” he told a BBC interviewer. “I think that is quite dangerous… You have to have security that prevents people firing off weapons where they can… But the idea you end up with a war on the streets is not a good thing. Surely you have to work to try and prevent these things happening. That’s got to be the priority.”

The problem with this lies not in what he said, but in what he didn’t say first. No one sane thinks shooting battles desirable, or wouldn’t be thrilled if they could be prevented. Of course the long-term priority must be to tackle the root causes of this psychosis. All of that would have been fine had he begun his reply by addressing the short-term priority: what to do when people with Kalashnikovs in their hands and bombs around their waists are rampaging through a British city.

To equivocate on that question is to commit suicide by media cop. The only beginning to that reply is on these lines: “Of course I would operate a shoot-to-kill policy – if, God forbid, it were needed. What do you think my policy would be? Send George Dixon in to greet them with a chirpy, ‘evenin’ all, now what’s all this palaver, then?’ and invite them down to the Dock Green nick for a cup of tea and a chat with the sergeant? You insult your audience’s intelligence by asking the question.”

The specially lethal thing about the answer he gave instead is that it projected a sense of detachment. We do not need more politicians engaging in mortal combat with one another to castigate these killers as more evil, monstrous, vile, despicable, cowardly, etc, etc, than the last MP to bluster the identical self-dramatising verities three minutes earlier. Of those we have a surplus. And we certainly do need more politicians who are prepared to go beyond the purely visceral, by talking about the complexities; the need to deal not only with immediate threats to security, but with the causes of that psychosis.

Specifically, right now, we need Corbyn to lead the opposition to a bombing campaign in Syria, by arguing with calm and cogent passion against indulging the reflex desire for vengeance which, so recent history teaches, will intensify rather than resolve the civil war there and the danger of terrorist reprisals here.

But a politician who comes across as devoid of visceral revulsion and fury about what happened on Friday in Paris represents himself as something other than the rest of us – and otherness on this scale will rob him of a hearing.

You can only talk about the need to avoid gun wars on the streets after stating definitively that preserving innocent lives, by shooting to kill if necessary, is paramount. You cannot speak about preferring the likes of Jihadi John to be tried in court without prefacing that with a plain declaration that – whatever one’s qualms about the execution of a British national – the world is a better place without him.

Francois Hollande used to be a utopian socialist known as “marshmallow”; now he sounds like Dubya on triple rations of testosterone. No one who admires and wishes him well wants Corbyn to replicate that journey by feeling obliged to say stupid things. But to get people to listen to intelligent things in times which demand ritual stupidity, a would-be national leader must first capture the mood of the nation he wishes to lead. Until now, Corbyn has spoken eloquently for a minority that has awaited a voice like his for too long. This week, sad to say, he spoke for almost no one but himself.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments