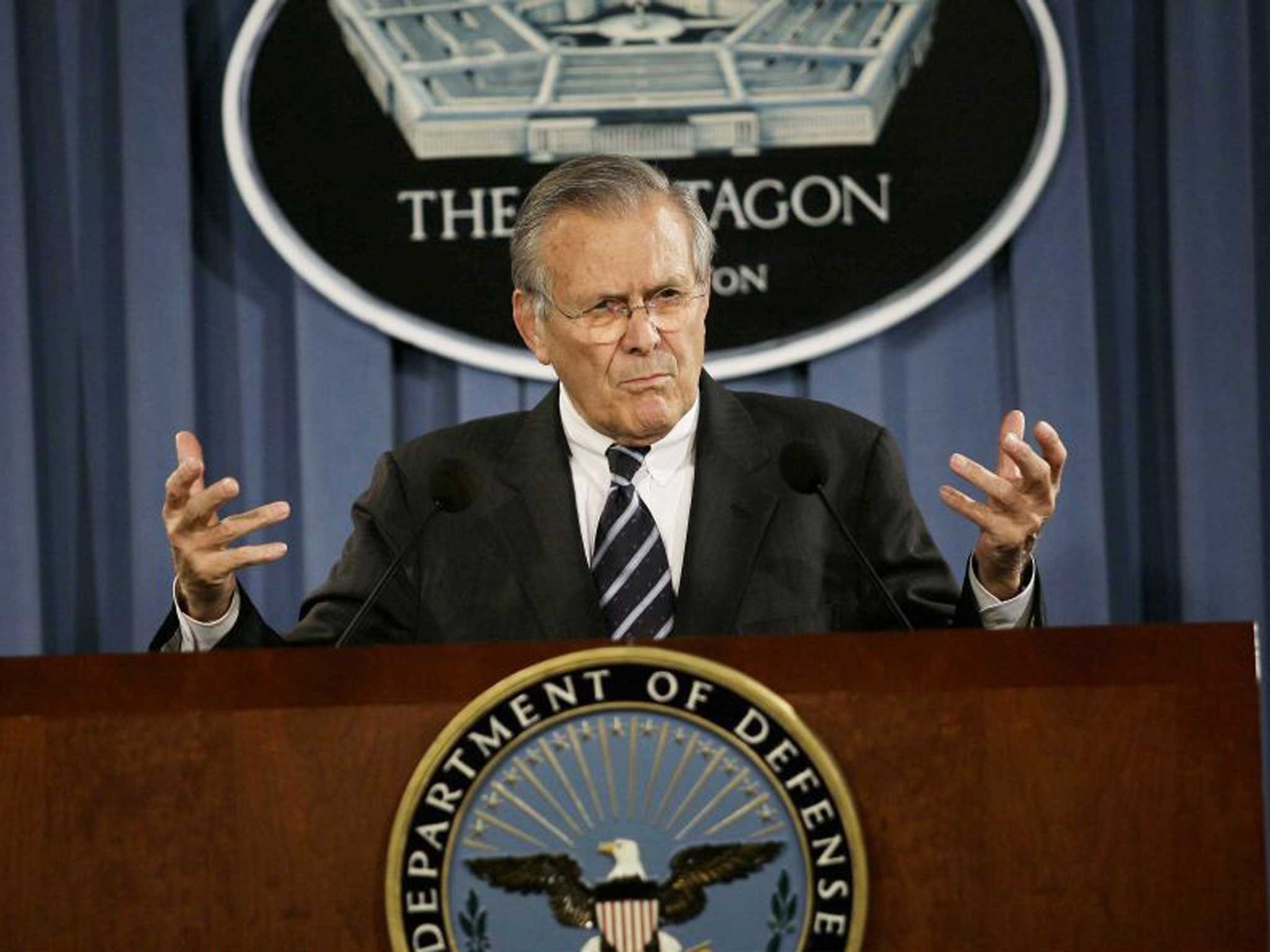

Donald Rumsfeld, the ultimate known unknown of American politics

Out of America: A documentary just out in the US shows the hard-nosed former defence secretary unapologetic over the Iraq debacle

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.One way and another, I've been writing about American politics and government for more than 20 years, and of the most inscrutable, most disconcerting and ruthless operator over those years, I've no doubt. Bill Clinton, George W Bush, even Dick Cheney? No, there's only one answer: Donald Rumsfeld. If you doubt me, then go and see the new documentary The Unknown Known, by the film-maker Errol Morris, about one of the two most controversial defence secretaries in modern US history.

The title stems from one of those whimsical nuggets for which Rumsfeld was famous, indeed for which he was once almost loved. Before we get into the bad Rummy – the bureaucratic thug who bested even such masters of the art as Henry Kissinger, the man seemingly without soul or core beliefs, adept at shuffling blame on to anyone but himself – let us remember he was briefly a national hero. In those traumatic weeks and months after 9/11, his truculent Pentagon press conferences, oozing authority and swagger, were the best free show in town.

Asked one day about evidence that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction, Rumsfeld delivered his celebrated epistemological riff about known knowns, known unknowns and unknown unknowns. And, of course, unknown knowns, "the things we think we know that it turns out we did not know". Or was it the other way round? Who cares? It made a splendid soundbite.

In the meantime, in cahoots with his old friend Cheney, Rumsfeld was running rings around Secretary of State Colin Powell (and, many would say, President Bush). Geoff Hoon, Rumsfeld's British opposite number, was by all accounts scared stiff of him. He wasn't a neocon, rather a hard-nosed pragmatist who believed that US military power was there to be used.

The other candidate for most divisive defence secretary is Robert McNamara, who ran the Pentagon during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations and was a leading architect of the Vietnam disaster. In his heyday, McNamara was regarded much as Rumsfeld is now, as arrogant and never admitting to error. But, in his case, that changed.

First, in a 1995 memoir, In Retrospect, and then in Morris's 2004 documentary The Fog of War, McNamara acknowledged that "we were wrong, terribly wrong" over Vietnam, as Washington failed to understand that the conflict was not part of a communist push for global domination, but a post-colonial civil war in which the US had no part. Talking to Morris, an anguished McNamara confronts the basic moral dilemma of war: "The human race must think more about killing … How much evil must we do in order to do good?"

Better late than never, those who can never forgive the US for what it did in Vietnam will dryly respond. But critics of the Iraq war should not look for any similar mea culpa from Rumsfeld. The only lesson of Vietnam, he declares, is that "some things work out, others don't". As for Iraq, whose post-invasion agonies he famously dismissed with the observations that "freedom is messy" and "stuff happens", his verdict is merely "time will tell".

Of remorse, there is none. Yet the Iraq invasion, of which Rumsfeld was a prime mover, was if anything a less forgivable war even than Vietnam – indeed, it was perhaps the greatest foreign policy blunder of modern US history. Vietnam was incremental, starting from modest beginnings and spurred by the understandable, albeit mistaken, belief that one more US push could settle things.

The invasion of Iraq, by contrast, was a hubristic war of choice. In terms of blood, if not treasure, it may have been less costly than Vietnam. But the consequences have been disastrous. Directly and indirectly, perhaps hundreds of thousands of Iraqis lost their lives, while Saddam's overthrow served only to advance the interests of America's real adversary in the region, Iran. Add to that the damage inflicted on America's reputation by Abu Ghraib and the like.

To be fair, Rumsfeld offered his resignation when those horrific images of the abuse of Iraqi detainees at the prison run by the US military became public. (Inexplicably, Bush refused to accept it.) But for the rest – torture, the inexcusable lack of post-invasion planning, the colossal intelligence failure over Saddam's alleged WMD – Rumsfeld either obfuscates or pins the blame elsewhere.

Yet the foreign policy consequences of Iraq are huge. If the earlier misguided war produced a "Vietnam syndrome" expunged only by the successful 1991 Gulf war, the post-invasion scars are at least as deep. In general, the US is less assertive on the foreign stage; in particular, fear of involvement in another land war in the Middle East has kept President Obama out of the Syrian conflict, when US intervention at an earlier stage might have limited the slaughter.

But Rumsfeld is not one for soul-searching. The only moment in the documentary when he shows real emotion is when he talks about the miraculous recovery of a wounded US soldier. For the rest, it is that smirk, the cocky sophistry of a man certain he's the smartest guy in the room, who will never be pinned down.

For that reason, The Unknown Known is fascinating stuff, but also unsatisfying and ultimately disappointing. Morris himself concedes as much. "I'm not interested in cracking the nut," he told Slate magazine earlier this month. "I'm interested in exploring the nut, if that makes sense." The end product is an old emptiness.

Watching the film, I was reminded of a day at school, when my classics master made a joke about the great political scandal of the moment. What, he asked us, was the Latin for "I throw up a smokescreen in front of"? The answer was "Profumo". "Rumsfeld" may lend itself to German jokes, not Latin ones. But the parallels are indisputable. Only this time the fog, the smokescreen, is unlikely ever to clear.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments