Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The forecast for Rio de Janeiro on the morning of the World Cup final is for rain; something Germans of a certain age still call “Fritz Walter weather”. It was sheeting down on the morning of what became known as “The Miracle of Bern”, a match that saw the emergence of the greatest nation in the history of the tournament.

Walter was captain of the first West Germany side to enter the World Cup and in the 1954 final they faced Hungary, the shortest-odds favourites ever to compete for the trophy.

When the two teams met in the group stages in Switzerland, Hungary had scored eight. Before the final was 10 minutes old, Ferenc Puskas’s side were 2-0 up.

Puskas, however, should not have been on the pitch; he was carrying an ankle injury and was playing on his reputation alone. The Germans were managed by Sepp Herberger, whose most famous observation on football was: “The ball is round, a game lasts 90 minutes, everything else is theory.” His team were no respecter of reputations. The Hungarian midfield was probed and prodded until it collapsed.

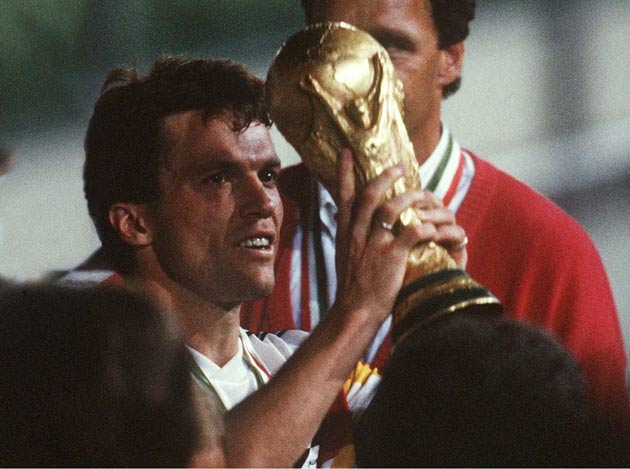

The game ended with a piece of commentary that has become woven into the nation’s fabric much as Kenneth Wolstenholme’s observation that “there are some people on the pitch, they think it’s all over” was to do in England. Commentating for German radio, Herbert Zimmermann, who had begun his broadcast hoping the Germans might keep the score down, shouted: “Germany lead 3-2. Call me mad, call me crazy.” Walter was presented with the Jules Rimet trophy in the rain.

In the 60 years since the Miracle of Bern, a German team has reached 10 World Cup semi-finals and gone on to six finals. England, which until the Football Association signed its own death warrant by sanctioning what was to become a foreign-dominated Premier League, possessed far greater resources. It has featured in two semis and one World Cup final and none of either since the Premier League came into being in 1992.

There are some clichés as to why the Germans dominate World Cups and some of them are true. They are better at penalties than any other nation. Curiously, English clubs have a better record at penalty shoot-outs than German teams – a conversion rate of 82 per cent to 75 per cent. However, at national level, while the Germans convert 93 per cent of their spot-kicks, England’s rate is 66 per cent.

Many attributed the 1954 triumph to “The Spirit of Spiez” after the lake-side town where West Germany based themselves. More than half the German side that annihilated Brazil in Belo Horizonte on Tuesday were graduates of the team that won the 2009 Under-21 title. Team spirit is very real and it shows itself on the penalty spot.

Before they played the 1954 World Cup final, Herberger made his team watch a film of Hungary’s 6-3 demolition of England at Wembley. That in itself was rare for the time but Herberger played it twice – the second time to point out the weaknesses in this unbeatable team. He was also close to the founder of Adidas, Adi Dassler, and ensured his players had removable studs. If it rained, as it was to do so famously in Bern, his players would screw in longer ones.

Sixty years later, Germany was virtually the only nation to anticipate Andrea Pirlo’s comment that there would be “two World Cups; one in the north, the other in the south”.

Italy, like nearly every other nation, based themselves in the south of Brazil. Their training camp at Mangaratiba was 1,770 miles from their first group match in Manaus, 1,165 miles from their second in Recife and 1,220 from their last in Natal. The Italians complained constantly about the heat and humidity of the north without doing anything to prepare for it.

Germany were the only major nation to base themselves in the north of Brazil, where, curiously, all their group games were. They constructed their own training complex that contained 14 villas, a spa, a pool, a fitness centre and pitches. It was the only piece of building work for the World Cup that was completed on time.

When West Germany won their second World Cup in 1974 they were based in what seemed like a prison camp an hour’s drive north of Hamburg. “Many of the team would have packed the whole thing in and gone home, such was the unmitigated pressure on us,” Berti Vogts was to recall later. “We slept three to a room; there was one telephone on the corridor and policemen everywhere.”

It was in that atmosphere that they lost was to become known as “Das Deutsche Duell” with East Germany, a result that sent the squad into meltdown and their manager, Helmut Schön, towards a breakdown. Franz Beckenbauer (below) effectively took over the team, shook it into shape, and led it to the World Cup.

In different circumstances, Michael Ballack would do the same 28 years later to a limited, unimpressive German side that had been humiliated 5-1 by England in Munich the year before and drag them to the 2002 World Cup final. “Anything can happen in football,” said his manager, Rudi Völler, “Except for Ballack getting injured.” Germany would probably have lost the 2002 final to Brazil had Ballack not been suspended. Without him they had no chance.

The Germans learned the lesson of 1974. In South Africa four years ago, Joachim Löw would take his young squad on safari or to visit Nelson Mandela’s old prison cell on Robben Island. Sometimes, they could be completely undisciplined.In his autobiography, Germany’s most infamous goalkeeper, Toni Schumacher, described a gambling and sex culture during the 1982 tournament in Spain that saw the team “come into training like a piece of wet cloth”.

It was that World Cup which was to colour views of German football for a generation. You could take your pick from Schumacher’s arrogant assertion that “we will probably beat Algeria by eight goals just to warm up” – they lost 1-0; the contrived game against Austria designed to send both teams through; or Schumacher’s taking out of France’s Patrick Battiston in the semi-final, for which he showed not the slightest remorse.

It took first Jürgen Klinsmann and then Löw to expunge the putrid images with a stream of young, highly-educated (in football and academic terms) players and a philosophy of one-touch football. And yet before the 2006 World Cup that was to begin the revolution, only three per cent of Germany’s population thought they had a chance of winning it – they were to lose an epic semi-final to Italy in Dortmund.

Klinsmann’s hiring of psychologists, experts from American sports and Germany’s hockey coach, Bernhard Peters, were seen as ridiculous gimmicks by Beckenbauer and the country’s most powerful newspaper, Bild, which in the face of dreadful pre-tournament results argued that if Germany could not withdraw from its own World Cup, then it should hire Ottmar Hitzfeld to manage the team.

The paranoia ended in a triumphant celebration by the Brandenburg Gate a victory over Portugal in the third-place play-off. The foundations were, however, laid down six decades ago and, when the first drops of rain fall on the Maracana tomorrow, Germans should look up to the skies and remember where it all began.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments