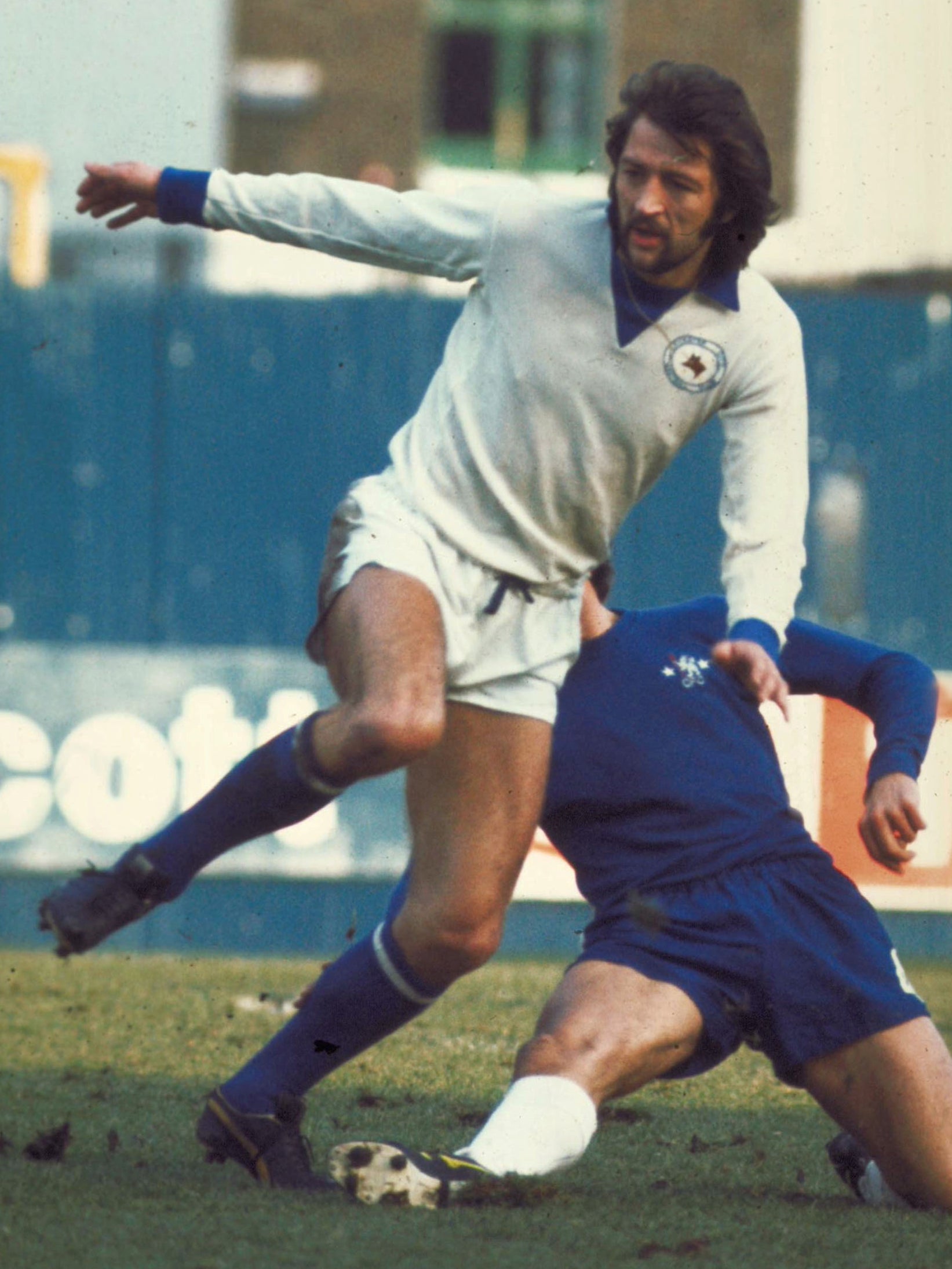

Frank Worthington: A stylish showman who never took himself, or football, too seriously

Sport thrives on childish wonder and Worthington, who has passed away aged 72, exuded it. Fans paid to see the free spirits and none was a bigger draw than him

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.An apocryphal story spread around Merseyside after Frank Worthington failed a medical to sign for Liverpool in 1972. The Huddersfield Town striker was suffering from hypertension and was sent on holiday for a week in Majorca before a second assessment.

Worthington’s idea of recreation was even worse for a manager’s blood pressure than his own. He returned from the Balearics after seven days of roistering that is said to have included a number of sexual encounters. Liverpool did not go on to sign him.

It did not matter whether it was true. The tale was entertaining and Worthington, who has died at the age of 72, was a showman. He loved the theatre of the game and loved to be centre stage.

There was always something about him that led people to believe the improbable. He wore cowboy boots, vivid velvet jackets and was a quintessential West Yorkshire dandy. That meant rugged: he was by no means a metrosexual. The lyric “He-man drag in the glittering ballroom,” from 5:15 on The Who’s Quadrophenia album could have been written for him. He strutted in stadiums and nightclubs. He was from the footballing wing of Glam Rock.

And, boy, he was glamorous on the pitch. Worthington had style. He could pluck a ball from the air, or even better, from the mud, and make it do things normal players could not even begin to imagine. In the 1970s there were a number of footballers who were regarded as ‘mavericks.’ Men like Rodney Marsh, Duncan McKenzie, Stan Bowles, Tony Currie and Alan Hudson seized on the tradition established by George Best and appeared to play as much for their own pleasure as the crowd’s - sometimes with a wanton disregard for the result. Most were derided as “fancy Dans.” Shankly was one of the first to criticise those he regarded as mere show ponies. Yet he wanted Worthington. Badly.

Read more

- Lewis Hamilton ‘being used’ by Black Lives Matter, claims Bernie Ecclestone

- Trent Alexander-Arnold’s England exile is not the most bizarre in Liverpool’s history

- Roman Abramovich launches defamation proceedings over Putin’s People book

- ‘It’s nice that it’s just the norm for us’: Life in the most gender equal sport on the planet

There is a modern myth that technique in English football is a recent innovation. On the quagmire pitches of half a century ago it often took remarkable ability just to make and receive a basic 10-yard pass. Worthington could do the simple things brilliantly. But that was no fun. It was better to flick the ball over a defender’s head and take it down on the other side. Or to nutmeg your opponent and skip over his statue-like leg. This, of course, attracted the attention of the hard men but the greater the intimidation, the more sublime the pleasure. Worthington danced past the tackles and, when he got the chance, left stud marks on the shins of his antagonists.

It was inspiring. In an age where ball juggling was sneered at, a generation of young boys took to the streets and parks in an attempt to emulate Worthington’s outrageous antics. A short clip from Match of The Day or one of ITV’s Sunday afternoon regional highlights shows would unleash the imagination of thousands of wannabee mavericks.

Televised football was rare. Worthington joined Leicester City and only supporters at Filbert Street got their regular dose of his panache. Around Anfield the sense of disappointment was palpable. His nickname was ‘Elvis’ and when he was in the building the queuing started early outside the Kop – and grounds across the country. Fans paid to see the free spirits and none was a bigger draw than Worthington.

Never one to be upstaged, he followed his Leicester teammate Keith Weller by wearing white women’s tights under his shorts on cold afternoons. The older generation fulminated. It pushed the ‘bricklayers in drag’ aesthetic ever further. Worthington could have stepped out of a ‘Carry On…’ movie. The game, and all its associated rewards and pleasures, were a jape. It did not matter that he won a mere eight England caps – international football was much too serious a place for eccentrics – or that by the 1980s his career started to resemble a band’s tour of increasingly run-down working-men’s clubs with the odd exotic foreign assignment. Everywhere he went, the entertainment levels rose and nightclub takings soared.

Worthington never took himself, or football, too seriously. He recognised what is so often forgotten: it is just a game. Sport thrives on childish wonder and he exuded it and generated it.

Could he have achieved more? He was leading goalscorer in the top flight in 1978-79 with Bolton Wanderers, which hints at his potential and he might have joined bigger clubs and built a medal collection. It would have required him to adapt his approach. Removing the traits that defined his personality would have made him half the player. He was the creator of myths, memories, mischief and joy.

The legends that surrounded him might not be altogether true but one part of the Shankly fable has veracity. Worthington had everything. None one could have enjoyed their career or life more.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments