After MPs backed assisted dying bill, what happens next?

MPs took a historic step towards legalising assisted dying as the piece of legislation cleared its first hurdle in the House of Commons. Albert Toth explains the procedures that lie ahead

MPs have voted to approve historic legislation that will pave the way for legalising assisted dying in England and Wales for terminally ill patients.

Open to a free vote, members were able to vote however they felt was right. Most had not publicly declared their intention going into the chamber, but 330 ultimately voted for and 275 against.

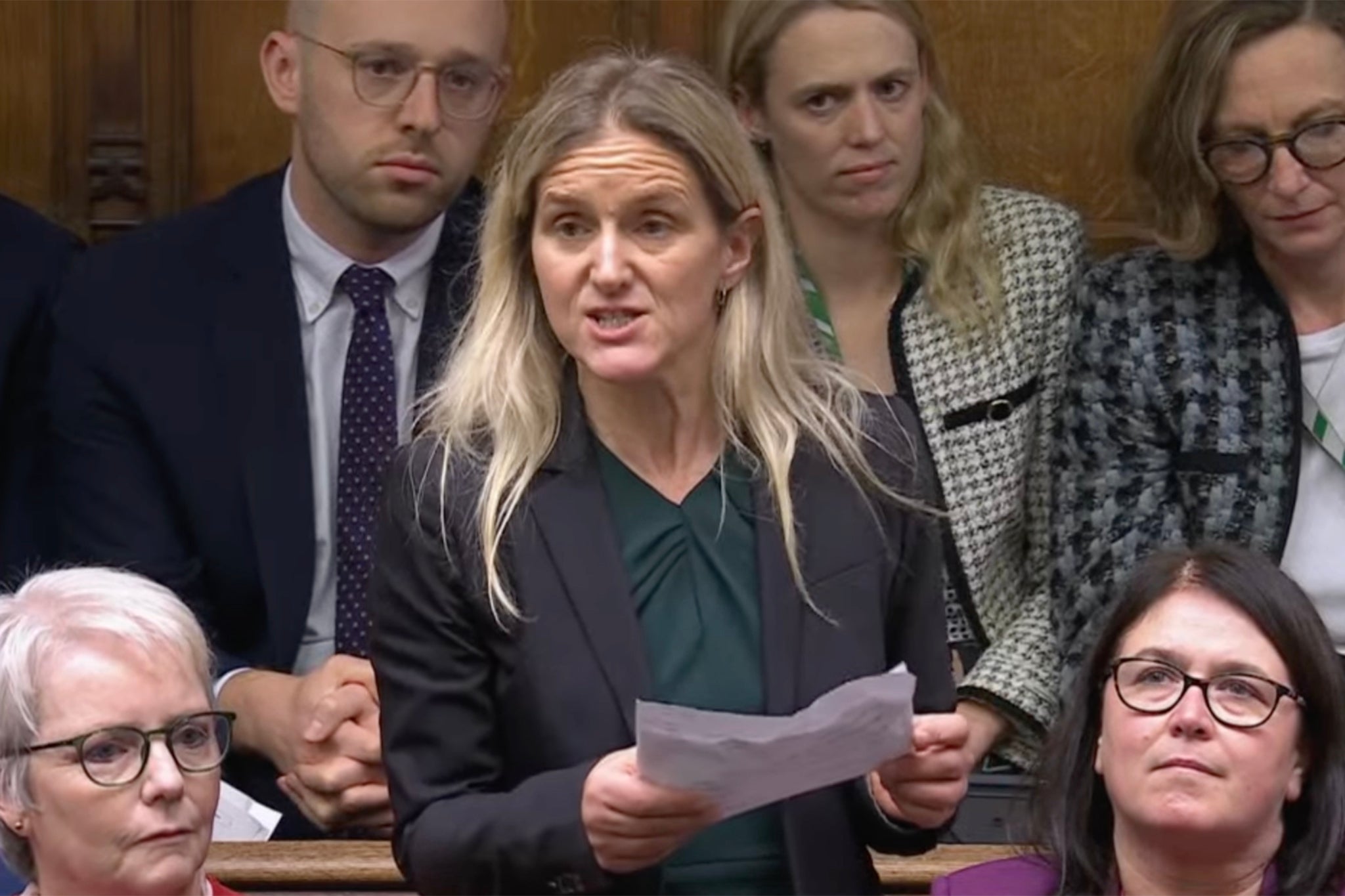

Proposed by Labour MP Kim Leadbeater in mid-October, the private member’s bill is lengthy, carrying strict stipulations about how the law is implemented.

To be eligible for assisted dying under the law, a person has to be over 18 years old, have proven mental capacity, have no more than six months left to live, and have the consent of two medical professionals.

MPs voted in the Commons at around 2.30pm on Friday 29 November after an emotional five-hour debate on the legislation.

Officially called the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill, the legislation has proven divisive since its proposal. Opponents have criticised a lack of safeguarding in the bill, saying its implications are too significant for the short amount of time allocated for debate.

Those who voted against it included health secretary Wes Streeting, Labour veteran Diane Abbott, and Lib Dem leader Sir Ed Davey.

But Ms Leadbeater says she doesn’t have “any doubts whatsoever” about the bill, telling Sky News that the safeguards it contains will be “the most robust in the world” and will “make coercion a criminal offence”.

However, now that the the bill has passed its first Commons hurdle, it is only agreed in principle. And so begins a process of months of further debate, scrutiny and amendment by both MPs and lords. Ms Leadbeater has said she expects the process to take a further six months – and it could be much longer.

First is the committee stage, where MPs make amendments clause by clause and the bill committee takes oral evidence from key stakeholders. Each clause must be agreed to, amended or removed, while new clauses can be added.

It’s a lengthy process, and almost always the longest stage of any bill’s passage.

More debates and amendments could happen after this, or the bill could pass straight to the third reading where MPs vote on it again. It is exceedingly rare for a bill to be defeated here.

Then, to the House of Lords, where a very similar process unfolds. Lords will debate the bill, possibly suggest and vote on new amendments, and then hold a vote.

If amendments have been made, they will go back to the Commons where MPs can reject them, agree to them, or propose new ones. If changes are made, the bill goes back to the Lords and the process continues until both Houses are in agreement about the final details of the bill. This process is often referred to as parliamentary “ping-pong”.

Then, at last: royal assent. The bill is sent to the monarch who will officially agree to make the bill an act of parliament. This is a ceremonial stage – the King will not reject the bill (the last time this happened was in 1708).

At this point, the bill is set to come into effect, but not immediately. The typical waiting period set for a bill to come into operation is two months, but it can be longer if ministers deem it necessary.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments