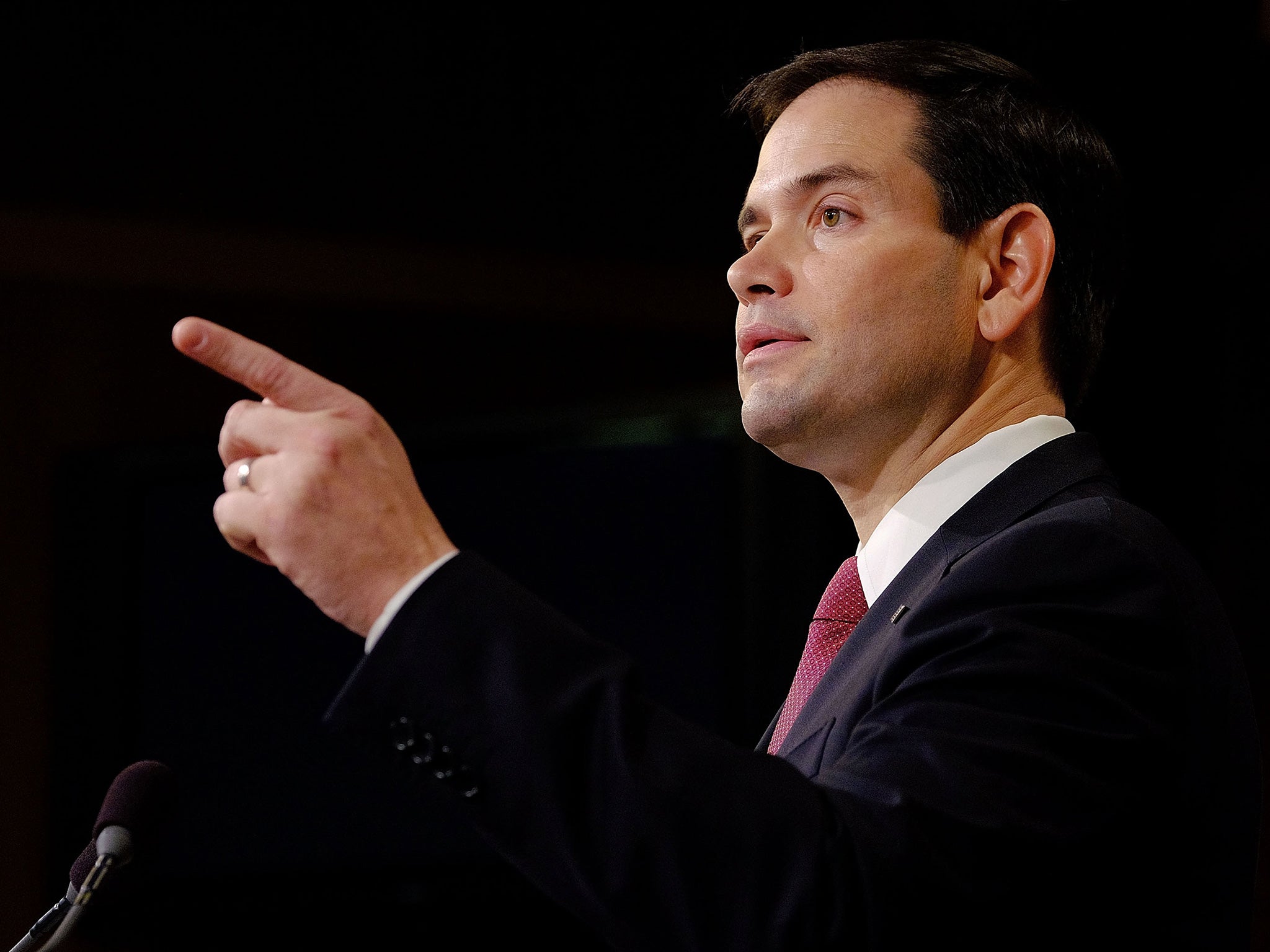

Marco Rubio profile: The ruthless rise of the Republicans’ best hope

The undoubted winner of Wednesday’s debate ticks all the boxes – but could those messy finances be his undoing?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Every so often, even the grimy business of politics can throw up a moment of coruscating brilliance – and the third Republican candidates’ debate on Wednesday evening did precisely that.

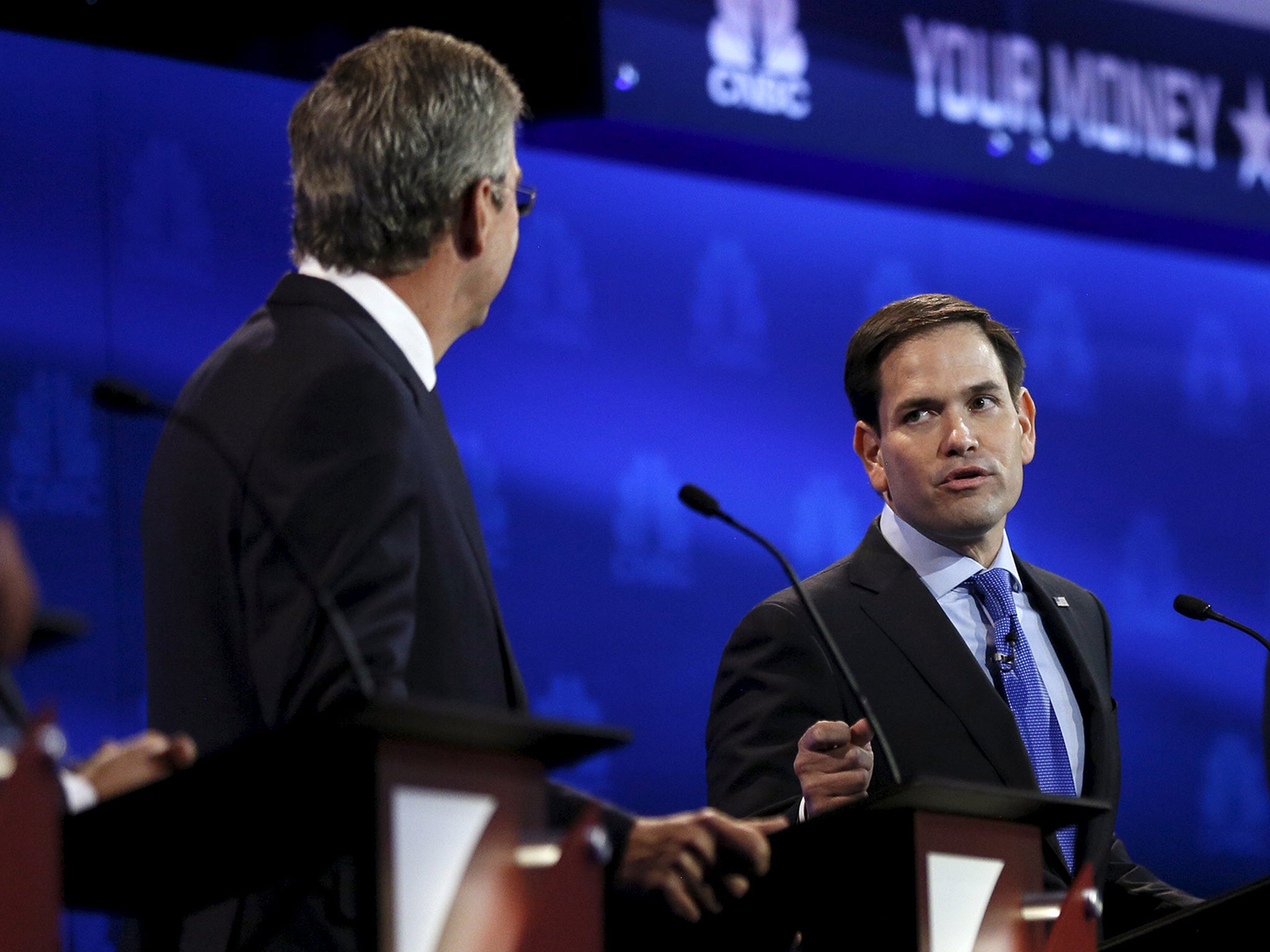

Jeb Bush, Florida’s former governor, was trying to rescue his hapless campaign and rounded on his one-time protégé turned arch-rival Marco Rubio, chiding him for his poor attendance record in the Senate. With the skill of a ju‑jitsu master, Rubio turned his opponent’s attack into a devastating riposte of his own.

First he produced chapter and verse on other presidential candidates (notably one Barack Obama) who had missed time in the Senate. Then Rubio suggested almost sadly that Bush was making a cheap attack out of desperation. And finally, he skewered him with deadly praise: “I will continue to have tremendous admiration and respect for Governor Bush.”

The exchange may prove the coup de grâce for Bush’s vastly disappointing candidacy. But in the space of a few seconds it displayed Rubio’s formidable political arsenal, featuring self-confidence and precociousness, eloquence and an ability to think on his feet, and – when required – a quite clinical ruthlessness.

More than ever, Rubio is the man to watch as this messy, volatile and endlessly fascinating Republican 2016 race goes critical. Don’t be fooled by those clean and youthful looks. Lurking behind them is relentless ambition and the sharpest of political brains. Some people are simply good at politics. Like Bill Clinton, that earlier young man in a hurry, Rubio is one of them. And even more than Clinton, he has an up-by-the-bootstraps “American Dream” life story to make image-makers salivate.

He’s nice-looking, a terrific speaker, unimpeachably conservative and a master politician

Rubio is the son of Cuban immigrants who came to the US in 1956 (not, as he once claimed, three years later as refugees from Fidel Castro). Once in America, Mario Rubio Reina worked mainly as a bartender, his wife Oriales as a supermarket clerk and hotel housekeeper. Marco was the youngest of three siblings, and spent part of his childhood in Nevada where the family lived for a while. He’s a Catholic but during his years in Las Vegas the Rubios attended a Mormon church – a link that may serve Marco well in the forthcoming Republican caucuses in Nevada, one of the earliest states to vote and where Mormons are hugely influential.

In 1984, when he was 13, the family moved back to Miami. After leaving high school, he spent a year at a Missouri college on a football scholarship (to this day Florida’s junior senator is a passionate Miami Dolphins fan), before coming home to attend university and law school, where he ran up $100,000 in student debt.

By then Rubio was showing a serious interest in Republican politics, working first as an intern for the Cuban-born Florida congresswoman Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, and then on the 1996 presidential campaign of Bob Dole. Four years later he won a seat in the state legislature, and the career that would lead to a starring role in Wednesday’s debate was born.

His ascent was rapid. State politics in Florida involves a complex mix of ethnic, age and interest groups, but Rubio, ambitious and crisply competent, soon learnt to play the game. In 2002, he was appointed Republican majority leader by the new speaker Johnnie Byrd. “From the day I first met him in the legislature, he kept coming up to my office… and he would say, ‘Give me a job. Give me a job,’” Byrd remembers. “And we kept giving him jobs because he kept performing.” Rubio excelled at the deal-making and arm-twisting essential for advancement – but also at keeping himself at one remove from the worst of it.

In 2006, Rubio, his progress fondly mentored by then governor Jeb Bush, was himself elected speaker – the first Cuban-American to hold the post. By tradition, the speakership is limited to a single two-year term. But no problem. Rubio’s sights were plainly set higher, and in 2010, one of Florida’s two US senate seats unexpectedly became vacant. The Senate, however, did not agree with Rubio. Its rhythms were too slow, the chains of seniority too strong for even the most gifted and energetic freshman to break. His legislative initiatives failed, most notably a bipartisan effort at immigration reform by a “Gang of Eight” of whom Rubio was one. “I hate the place,” he reportedly told a friend. His attendance plummeted, and on 13 April 2015, he announced his presidential bid, making clear his Senate days were done.

Within weeks, pundits were marking Rubio as one to watch in a crowded Republican field. More than any of his rivals (with the possible exception of Scott Walker, who has now withdrawn), he could appeal to both the Tea Party and establishment wings of the party. Poll after poll showed him to be the most acceptable second choice for supporters of other candidates.

As a potential nominee, he ticks almost every box. He’s nice-looking, a terrific speaker, unimpeachably conservative and – as that exchange with Bush demonstrated – a master politician. Even without embellishment he has a compelling personal story. Rubio comes from a vital swing state, and his Cuban background and previous support for immigration reform should help him with ever more numerous, and traditionally Democratic, Hispanic voters. His wife, Jeanette, with whom Rubio has four children, adds to the appeal. Though she has thus far shunned the spotlight, she was not only Rubio’s college sweetheart, but a former cheerleader for the Dolphins. Completing the picture is the senator’s young age.

That is not an unmixed blessing. Republicans rail against Obama’s youth and inexperience, so why should Rubio, another first-term senator, be any different? Obama and Clinton were both 46 when they reached the White House. Rubio would be only 45. Then there’s his, shall we say, unusual financial background for a candidate.

Marco Rubio is not great when it comes to money. On the campaign fundraising front, he hasn’t excelled – though that may change after this week’s strong debate performance. His personal finances, meanwhile, have on occasion been downright messy. A student loan is one thing; missing mortgage payments, cashing in early a $68,000 retirement plan and splashing $80,000 on a speedboat are quite another. In his 2012 memoir, An American Son, Rubio himself admitted to “a lack of book-keeping skills”.

But like his youth, which enables him to connect with a generation his party struggles to reach, his financial troubles may also be of political benefit, giving him an everyman appeal Republicans so often lack. Many ordinary Americans can relate to his financial troubles – even if they can’t count on a Senate salary of $174,000, or the $800,000 advance Rubio received for An American Son, to get them out of the hole.

Perhaps, somewhere in his shaky finances lay the vetting issues that made Mitt Romney wary in 2012. After Rubio’s success this week, the media spotlight is certain to intensify and other embarrassing revelations may emerge. But if his handling of Bush is anything to go by, he can handle these too. And failure this time surely would not mean the end of Marco Rubio’s political career. There’s the Florida governor’s race of 2018. And in 2020, the White House will beckon again.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments