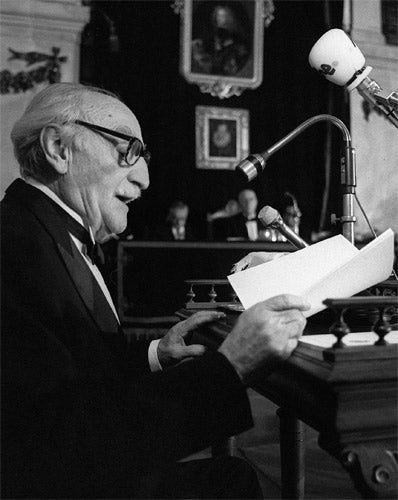

Francisco Ayala: Author and essayist who found his voice in exile and whose work dealt with power and its abuses

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This great Spanish novelist, short story writer and essayist was truly a universal man. He considered himself European rather than Spanish right from the start of his career.

Though he began his studies at the University of Madrid, he followed courses in Germany from 1929 to 1930, and later made translations from Rilke and Thomas Mann. He became a jurist and a sociologist, and was professor of Sociology and Political Science at the University of Madrid between 1933 and 1936, where he composed early sociological and literary-critical works as well as his first attempts at fiction. In 1939 he was forced into exile to escape Franco's regime, and taught at various South American and US universities, before returning to his homeland in 1976. There, he was awarded many literary honours, including the Cervantes Prize.

The Spanish Civil War and Franco's long, repressive regime were, paradoxically, the originators of a literature of exile producing works of widely different forms and aims. Francisco Ayala, who was born in Granada in 1906, became a really great writer only after he was forced to leave Spain. Some exiles, like Ramon Sender, found in exile a creative liberation and worldwide fame. Ayala, like many others, chose Latin America, so as not to completely lose touch with his own language and cultural roots. Other writers in exile remained obscure or totally ignored, both in their own land and abroad, when cut off from their native inspiration. "For whom do we, the exiles, write?" Ayala once asked, and answered: "For everybody and for no one." Fortunately, he was one who wrote finally for everyone, though he always remained a man of Granada, proud of his origins.

It took 20 years of effort for him to produce his first major work, a collection of classic, lucidly written short stories, Los ursurpadores, that was published in Buenos Aires in 1949 (and in the UK as Usurpers in 1987). Unlike Sender, he was not a consciously "engaged" writer in the popular acceptance of that term. Indeed, he rejected all forms of engagement, whether literary, political or social, and refused even to attack those guilty of fomenting the Civil War, which he simply explained as just another expression of the Spaniards' hereditary impulse to kill one another – a caninismo (doggishness) that persists to the present day. So in his short stories, Ayala's aim was to demonstrate that power is always the usurpation of others' rights.

The most powerful of these brilliantly ferocious tales, El hechizado ("Hexed") portrays a humble subject who attempts to approach the "supreme" head of state in an atmosphere of increasingly Kafkaesque irreality. When he finally succeeds, he discovers a paltry, nondescript individual, only half human. The reference to Franco is subtly oblique in this moral allegory full of stinging irony, but detached, unemphatic, non-judgemental. In a similar vein he shows the rottenness at the heart of the Civil War in another collection, La cabeza del cordero ("The Lamb's Head"), also published in Buenos Aires in 1949, and published in Spain only at the dog-end of Franco's protracted dissolution, in 1972. "It is for us, the Spaniards", Ayala was to write, "to look on the world with an eye that, while it does not reject or repress the usual manifestations of evil, brings them a little more to the surface of common consciousness, in order to purely and simply annihilate them". It is this "look" that defines his concept of literary affirmation, and the duty of a "responsible" writer.

His first novel, Muertes de perro (1958) – again published in Buenos Aires, as Death as a Way of Life in English in 1964, and not until the 1970s in Spain – takes the same, but even more bitterly ironic stance in a complexly plotted story of power struggles and dirty little doggy doings behind the scenes in a decrepit South American dictatorship. El fondo del vaso ("The bottom of the glass") 1962, is a sequel in the same brutish tone, with characters who are inhuman, symbolic of all forms of human rottenness.

Ayala's technique is one that became increasingly popular with serious novelists: a fracturing of the logical narrative, with "exploded" character portraits, a style that requires a great deal of the reader, who is sometimes quite disorientated. But the difficulties he proposes, always in a clear, almost transparent style, are well worth tussling with for they have a purpose; to present us with the broken patterns of our relationships, and with life itself.

El jardin de las delicias ("The Garden of Earthly Delights", 1971), is a perfect example of such confused fragmentation, inspired by the famous painting of the same name by Hieronymus Bosch – a grotesquely patterned, nightmarish confusion of surreal images of half-human faces, of creatures half men, half beasts or fish. Despite the horrors, Ayala's treatment makes this an unforgettably beautiful work of art.

Ayala's 100th birthday was celebrated with a year of conferences, seminars and exhibitions that began with dinner with the king and queen of Spain. In an interview shortly before his centenary, Ayala was physically fragile but mentally alert.

"I've been a part of the past for the last few years," he said. "There comes a time when calculating age rationally, you know you're not going to get much further".

Francisco Ayala, novelist, essayist, critic: born Granada 16 March 1906; married firstly (one daughter), secondly Carolyn Richmond; died Madrid 3 November 2009.

James Kirkup died in May 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments