Lord Waddington obituary: Chief Whip and former Home Secretary was loyal supporter of Margaret Thatcher

The peer resisted calls to end the BBC licence fee and ordered an inquiry into the ‘Birmingham Six’, who were wrongly convicted of an IRA bombing

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.David Waddington, a Chief Whip and Home Secretary in Margaret Thatcher’s last Cabinet, has died at the age of 87. She liked his bluff, no nonsense Lancastrian approach, but the posts taxed even his notable stamina and steady hand. He was called “Junior Atlas” because he looked as though he had the burdens of the world on his shoulders. Ms Thatcher regretted she had not retained him as Chief Whip when she was on the point of resigning as Prime Minister.

As Chief Whip he was accused of misleading Sir Geoffrey Howe in 1989, by implying the coming cabinet reshuffle would not affect his position as Foreign Secretary. This was designed to prevent the possibility of Howe from mobilising support in the party or press against such a move. When the deception was revealed, Howe never forgave him.

As the first pro-hanging Home Secretary for 20 years Waddington was the only one of Ms Thatcher’s Home Secretaries who ever shared her outlook. The Home Office still bore the liberal imprint of Roy Jenkins’s tenure (1965-67), which Waddington’s Conservative predecessors had done little to challenge. His own reform agenda was effectively destroyed by the spectacular 25-day siege at Strangeways Prison in April 1990. The front-page pictures of defiant prisoners trashing Strangeways were a daily humiliation for him.

Born in Burnley in 1929, David Waddington was the youngest of five and a man with deep roots in that part of Lancashire. From fighting the hopeless Farnworth constituency in 1955 to the safe Clitheroe (later Ribble Valley) in 1979, he never looked outside the area for a seat. His father and grandfather were both solicitors in Burnley. Of medium height, fair-haired, wiry, and energetic, he was combative in Parliament. He once recalled that at a political rally with Ms Thatcher his hand had strayed to her knee. He then had the delicate task of removing the offending hand before she noticed.

After boarding at Sedbergh in Cumbria, he read law at Oxford and was President of the University Conservative Association in 1950. He qualified as a barrister in 1951 and then spent the next two years on national service in Malaysia. Recalling time in Suez he described the canal’s banks being lined with “masturbating Egyptians – a very exhausting form of political protest”. Ever the gentleman he once rescued Princess Margaret from embarrassment. At a reception festooned with “no smoking” signs she approached him with an inch of ash at the end of her cigarette. He bowed, received the ash and put it in his pocket.

Waddington’s interests in Tory politics and in Lancashire were combined in his decision to marry Gillian Green, daughter of the Conservative MP for Preston South. The long and happy marriage produced five children. Family mattered greatly to him but his ambition and success in politics and law meant that they had to fit in with his career. He was elected as MP for Nelson and Colne in a by-election in 1968, on the death of the anti-hanging Sidney Silverman, defeating Labour’s Betty Boothroyd. He held the marginal seat until he lost it in October 1974.

As a QC (1971) and a recorder in the Crown Court he could fall back on a thriving legal career whilst he was out of Parliament. In 1976 he defended Stefan Kiszko who was accused of murdering a young girl in Rochdale. It turned out to be a miscarriage of justice and Kiszco served 16 years for a murder he did not commit and the defence team was criticised. He returned to Parliament by winning the safe seat of Clitheroe in the 1979 general election. He lived in the constituency and when it was substantially reorganised as the still safe Ribble Valley, retained it until his retirement in 1990.

In 1981, Ms Thatcher appointed him under secretary at the Department of Employment under Norman Tebbit. He introduced the Employment Act in 1982, which made the unions liable for damages arising from unlawful industrial action and restricted the closed shop. In 1983, he began a four-year spell at the Home Office, in charge of immigration. He relaxed the ban on the entry of fiancees of Asians but made no secret of his embarrassment at the granting, in record time in 1984, of citizenship to the young Zola Budd, the South African runner, following a pro-Budd campaign by the press. More popular with the right were his repatriation of an illegal Romanian immigrant, denial of asylum to more than 50 Tamils, and his deportation of Viraj Mendis, a Sri Lankan dissenter, who had taken refuge in a church in Manchester.

He succeeded John Wakeham as Chief Whip in 1987. In this post he was forceful and, though lacking the personal skills of his predecessor, was a success, despite rebellions over the community charge.

But his appointment in October 1989 to the post of Home Secretary, one of the highest posts in government, surprised many, including him. A reshuffle was forced by the sudden resignation of Nigel Lawson, the Chancellor. Waddington recommended Norman Fowler as Douglas Hurd’s successor at the Home Office and was astonished when Ms Thatcher told him that he was to become the new Home Secretary. On the day of his appointment Stefan Kiszco lodged his appeal which eventually cleared him.

At the Home Office, Waddington felt that officials regarded ministers as birds of passage, coming and going while they endured. He took over the Criminal Justice Bill from Douglas Hurd. Waddington did not like the proposal to base fines on the gravity of the offence and the offender’s ability to pay; he toughened up the parole provisions, to ensure that prisoners served at least 50 per cent of their sentences. Having opposed reopening the case of the “Birmingham Six”, who had been convicted for an IRA Birmingham pub bombing in 1974, he ordered an enquiry following new revelations. When it uncovered police fabrication of the evidence, he referred the case to the Court of Appeal, which eventually ordered the release of the prisoners.

An early policy decision was to kill off Ms Thatcher’s favoured scheme of football-club membership identity cards, an idea she fastened on to in the wake of the Hillsborough tragedy. He also resisted her call to end the BBC licence fee. When the War Crimes Bill was defeated in the House of Lords in 1990, he and Ms Thatcher defied ministers who wanted to drop the bill. The bill gave British courts jurisdiction over people who had committed war crimes in Germany or German-occupied countries in the Second World War, and were now resident in or citizens of the UK. Waddington felt that, after Strangeways, he was living on borrowed time as Home Secretary. He had been dissuaded by some civil servants from using force to reclaim the prison. He was also under pressure over the poll tax riots in London and a son leaving Cambridge because of mental illness brought on by cannabis.

In November 1990 he was one of the last Cabinet Ministers to meet Ms Thatcher when she was deciding whether to contest a second ballot against Michael Heseltine for the party leadership. In tears he told her she could not win but that he would still support her. He voted for John Major in the subsequent leadership ballot.

The new Prime Minister, John Major appointed Kenneth Baker Home Secretary and asked Waddington to become a “Whitelaw” type figure, acting as a broker on his behalf with other Cabinet ministers and chair several important cabinet committees. He was also offered the chance to be Leader of the House of Commons, but surprisingly turned it down, accepting instead a peerage and the post of Leader of the House of Lords.

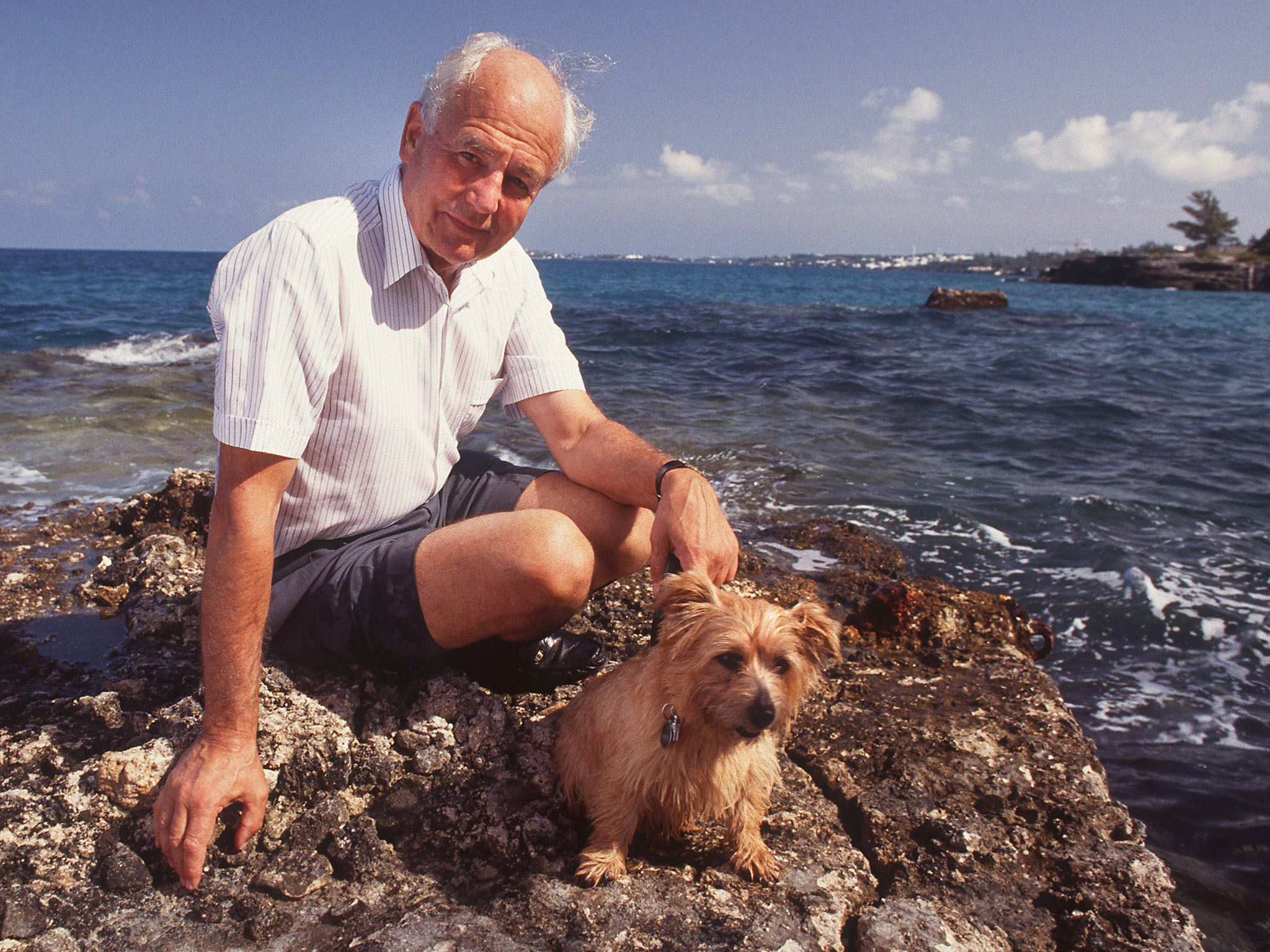

This arrangement was doomed and an unsatisfactory end to his political career. As Lord Waddington of Read, he surrendered his beloved Ribble Valley constituency, which the party humiliatingly lost in the ensuing by-election. He was not an effective Leader in the House of Lords and Major made little use of the so-called Whitelaw role. Waddington privately described his decision as “the biggest mistake I have made in my life”. In 1992, he accepted an appointment as Governor and Commander in Chief of Bermuda, a post which he held for five years.

Bermuda was relaxing and he took time to improve his golf. But such a driven man had never had time for hobbies or to relax for long. He was glad to return to London and was a frequent attender at and speaker in the Lords until his retirement on health grounds in March 2015. Lord Waddington, who died on Thursday, is survived by wife Gillian.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments