Men and bulimia: Why suffer in silence?

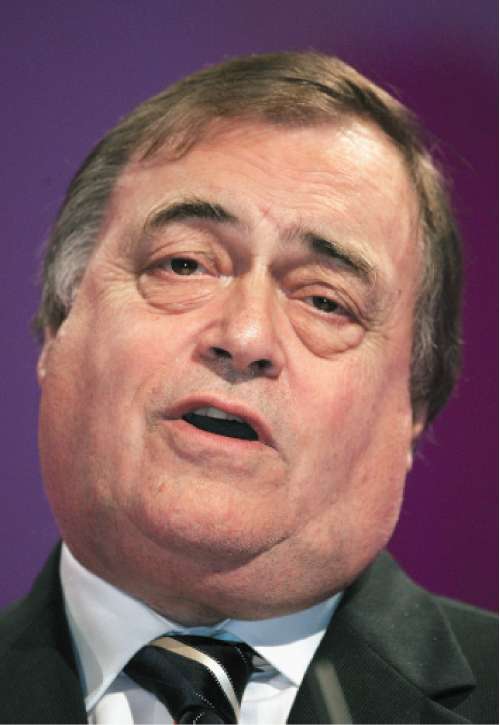

Matthew Campling battled against an eating disorder for years. But like John Prescott, he felt too ashamed to admit it. Now he's helping others to face their demons

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Many people have said how surprised they are that John Prescott suffered from bulimia for 20 years, but it's no surprise to me. As a psychotherapist, I have treated several men battling eating disorders and I have suffered from anorexia myself. I'm only sorry Prescott didn't say it when he was deputy prime Minister, though I realise he was probably never going to do that. One positive thing to come out of this is that it might help people to start conversations about their own relationships with food. It's not an easy thing to do.

My problems started when I was 10 years old. My parents had moved us to South Africa, which was an overwhelming change for me. We arrived at the height of apartheid and I found the appalling iniquities and day-to-day violence hard to deal with. It seemed the only people who did well in South Africa at the time were those who didn't care. If you had any sense of what was right you had a problem and, during my teens, I turned to food for comfort and for safety. I went from being a happy little chappy in England to becoming overweight, anxious and bullied.

I left school when I was 17 and wanted to change, so I started exercising and dieting. I enjoyed feeling the burn and the adrenalin I got from running or swimming, but for me the reward was not eating. When I did eat, it was a failure. Aged 18, I weighed 11 and a half stone. Two years later, my weight dropped to a low of six stone and six pounds. I was working at an advertising agency and would start crying and not be able to stop, so they put me on sick leave. I was at home and unable to go to work. It was at that point that I accepted I was ill and out of control – that something inside me was preventing me from eating properly. I had anorexia.

Suffering from an eating disorder is like having a mechanism inside you – something that wakes up and starts to run your life. It might start as a defence mechanism, but then it takes over and sometimes manifests itself as a voice. I've had clients tell me that their disorders tell them to do things. It can be quite specific. It's the same feeling or voice that also tells people not to say anything to anyone, or else "for God's sake, something terrible will happen – it's our little secret". Like with an abused child, the only way out is to ignore that voice and tell someone, but it isn't easy.

For me, it was difficult because you cannot hide anorexia. My brothers would tell me I looked like I had come out of a concentration camp. A colleague – a former model – told me I was so thin it made her sick to look at me. Other people would tell me to eat, which doesn't help when something else is clearly stopping you from eating. By contrast, you can hide bulimia. I've had clients who are thin and bulimic and others who are overweight. Bulimia is about the taking in and the purging. Somebody who is overweight when they develop an eating disorder will hold on to that weight.

I never felt shame while I had anorexia, but in bulimics the sense of shame plays a big role in the illness, which is something Prescott has talked about. There is also a sense of punishment. John Prescott has talked about how he used to binge on junk food. Bulimics generally don't go out and pay a lot of money for a nice meal – they'll go to a chippie and eat the chips when they're cold and horrible. Or they'll retrieve food from the bin and eat things they don't even like. They're not doing it for pleasure but to satisfy something inside them. Something that is saying, "Look, this is what a disgusting person you are – you're eating all this horrible food and now you're going to throw it up and now you're going to have to clean it all up."

When bulimia is bad, it's terrible. It isn't rare for people to binge eat and vomit 10 times a day. I've had people contacting me and saying they are throwing up 20 times a day. They get to the point at which the voice inside them is so strong that anything they take, including a drink of water, has to come back up. In the worst cases, sufferers basically starve to death. Bulimia has one of the highest mortality rates of any mental illness – I've seen figures from 6 per cent up to 18 per cent.

Most people who develop eating disorders do so in their teens, but we see children as young as six or seven developing disorders. I also know people who are middle aged who are developing eating disorders as a way of trying to freeze time. And there are more men admitting to having bulimia and anorexia. Men are less likely to talk about problems with eating. I can imagine a woman mentioning to a friend that she's got a problem with food, but in a more macho environment, you're not going to get those conversations.

For the same reason, a high proportion – 20 per cent – of men suffering from eating disorders are gay. Again, I think they are more likely to look inwards and to their emotions. I also think the images of men we are fed in the media have an effect. When I had anorexia, it was about peer pressure and people judging me. Nowadays it has also become about the impossibly toned guys you see on magazines. I know a man in his fifties who spends two hours a day in the gym and has a very slim, muscled body. That's not normal for a 52-year-old. Then there are the young male models you see in the weekend supplements, who are starting to look as thin as the women. It's a questionable fashion and one that, I think, has the potential to be very damaging.

It took me almost a year of very careful work for me to regain control of my eating and gradually build up my weight. There was a moment when I was swimming one morning as the sun came up and hit my long hair and shone into my eyes. It was a wonderful image of life and joy and that's the kind of thing that can turn a person around when they're getting over something like this.

After I had recovered, I moved back to England via the US and trained as a psychotherapist. For 10 years I didn't treat anybody with eating disorders, but then I read an article about a surge in anorexia and bulimia so started to write about my experience for journals. I also started to see clients with eating disorders and last year I wrote a book, Eating Disorder Self-Cure.

I hope John Prescott's revelation means more people with eating disorders will make contact in the future. Too often, the time when men get help is when they've gone too far and are being treated in hospital. They should know that it is possible to recover – and fully. But it's like breaking a leg – although it heals and you can walk again as if nothing ever happened, the bone doesn't heal in exactly the same way as it was before.

* www.eatingdisorderself-cure.com

Bingeing and purging – the facts

*John Prescott is not the first well-known man to own up to bulimia. Elton John, Paul Gascoigne, Uri Geller and Rory Bremner have all had the disorder. The most famous female sufferer was Diana, Princess of Wales.

*Bulimia still carries stigma and it was only in 1979 that it was recognised as an eating disorder in its own right.

*Sufferers will usually have the uncontrollable urge to consume very large amounts of food, then to purge by means of vomiting, taking laxatives or by slashing food intake, or a combination of these methods. A bulimic's weight may fluctuate considerably.

*Sufferers rely on controlling food and eating as a way of coping with emotional difficulties. The condition is associated with low self-esteem and a lack of self-confidence.

*It is not uncommon for a bulimic to eat two, three or four times a normal amount of food in one go. But with the feeling of fullness comes the sense of shame and the urge to purge.

*The effects of this chaotic pattern may be sore throat, tooth decay and bad breath from excessive vomiting; swollen salivary glands, making the face rounder; poor skin condition; hair loss; lethargy, and loss of libido. There is an increased risk of heart problems, and of impacts on other internal organs.

*Treatment for bulimia involves counselling and cognitive behavioural therapy. There is evidence that antidepressants may help. Many sufferers find self-help and support groups, such as the ones run by Beat, the eating disorders charity, very helpful.

For more information go to www.b-eat.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments