This is what we need to understand about the ‘science’ of coronavirus

The characterisation of science as a fixed thing in this emergency isn’t helpful, says Ben Chu. The reality is that the advance of scientific knowledge is often a messy and ‘emergent’ process, unfolding over time rather than in a flash of discovery

Oh for a beaker of the scientific controversy of normal times.

Drinking wine’s good for you, says one news headline.

No wait, wine’s actually bad for you, says another.

We ask ourselves: why can’t the confounded scientists just make up their minds rather than giving us such conflicting and confusing advice?

Sometimes the problem is inaccurate or sensationalist reporting.

Sometimes it’s been misleadingly presented or overhyped by the researcher in the press release.

Yet sometimes the appropriate answer is that: science doesn’t actually work like that, particularly in a field like the study of disease, epidemiology.

Different teams of researchers, studying different populations, find different results.

There is no single scientific “mind” to be made up.

Over time, if we’re lucky, we tend to get a clearer picture, because numerous independent studies point in a similar direction. Think of the science of man-made global warming and its ecological impacts.

But science is often a messy and “emergent” process, unfolding over time rather than in a flash of discovery.

Which brings us to the science of Covid-19.

A newly released study from epidemiologists at Oxford University hypothesises that half of the UK population has actually already been affected by this novel coronavirus, often without knowing it or showing any symptoms.

It’s received a good deal of attention. And understandably. Because, if the assumptions of this study are true, the implications would be profound.

It would mean that the fatality rate – the proportion of people likely to die from contracting the virus – is significantly lower than the range official experts have hitherto been assuming.

It would also mean that we could look forward to a much earlier lifting of the social lockdown than otherwise.

It would mean that we have already built up a degree of herd immunity to the virus, making the threat of being hit by another wave of disease later in the year significantly lower.

It would, in short, be good news.

But is it true? We simply can’t know. But it’s worth probing, as the Oxford study authors say, through large-scale blood testing.

If significant numbers of asymptomatic people turn out to have antibodies against this virus, that will give statistical support to the hypothesis.

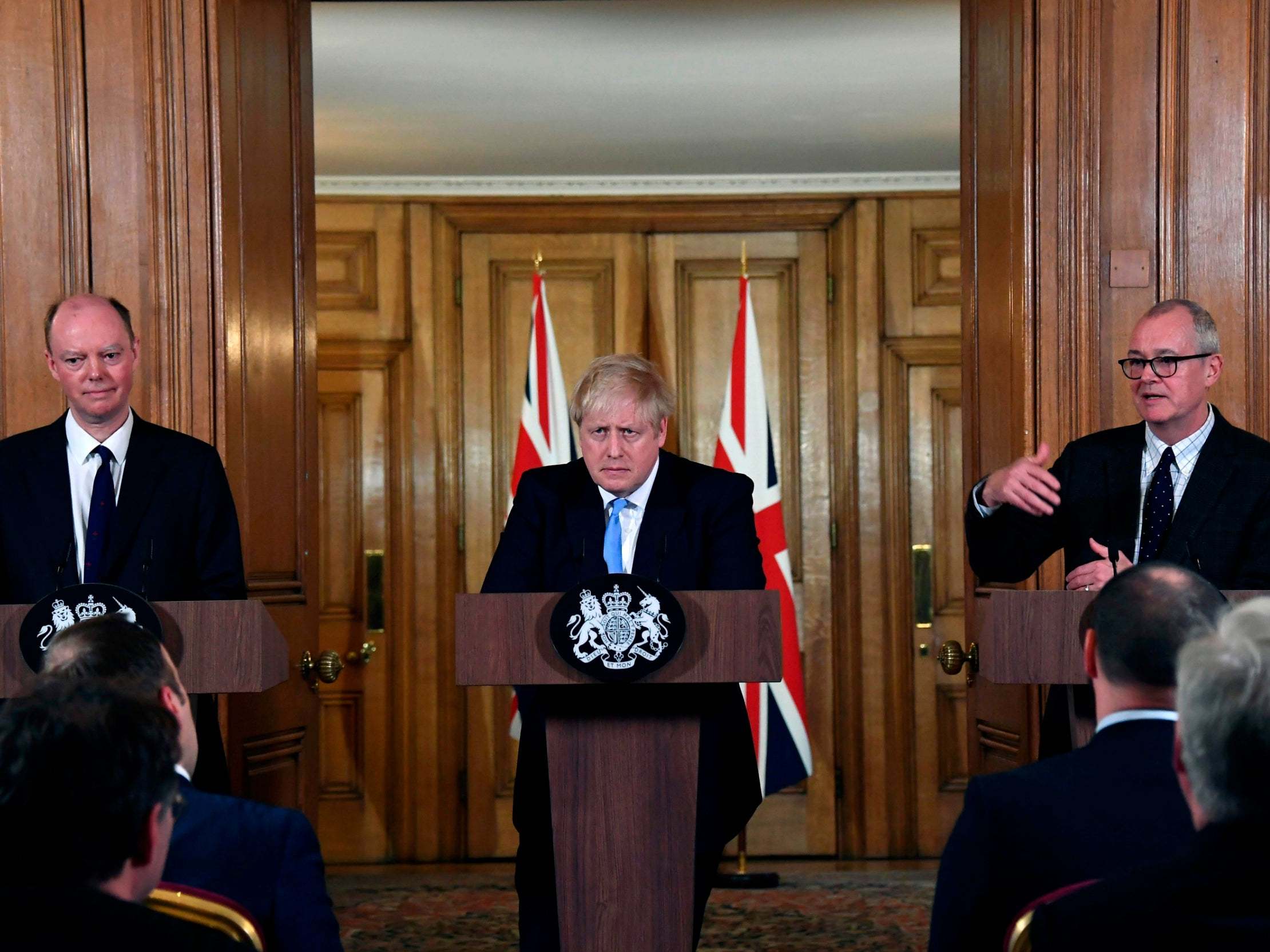

Boris Johnson says that throughout this crisis his government has been “led by the science”.

The claim that the science changed suddenly last week – when the government suddenly shifted from a mitigation to a suppression strategy for the virus – has been met with derision in some quarters.

The science has long been crystal clear, insist critics. Spiralling infection and hospitalisation rates in Italy were obvious. The government should have ordered a total lockdown of the UK economy and society weeks ago.

Perhaps it should have done.

Yet the characterisation of “the science” as a fixed thing here isn’t helpful and could even be dangerous.

There is no science as such, rather an array of scientific evidence which requires judgement by experts and policymakers to interpret. And the reality is that in a pandemic like this one new scientific information – about fatality, recovery and transmission rates – is constantly emerging. New information about total infections could change the whole game.

It’s important to note that epidemiological projections of the spread of a disease requires computer modelling. And experts can differ on the appropriate parameters, or inputs, to those models.

By all means, question the judgements made by politicians – and even experts like the chief medical officer and the government’s chief scientific advisor – about the evidence available. Ask whether the parameters of the modelling being used are appropriate. Ask whether the models are up to date given the new information continually emerging.

Indeed, it’s vital that is done by other independent experts, and regularly, to counter the perils of groupthink among policymakers.

But let all of us, also, try to be a bit more sophisticated about the nature of “science” in a situation like this.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments