‘You shouldn’t have to fight this hard’: How the HRT shortage is causing suffering among women

Menopause is often treated as simply a ‘women’s issue’ as if feeling well was a luxury, not a necessity. Now there is a shortage of hormone replacement therapy and hundreds of thousands are struggling, reports Hannah Fearn

Diane Danzebrink snorts when she is informed the health secretary, Sajid Javid, is to appoint an “HRT tsar” to sort out the hormone supply crisis that is devastating many women’s lives and leaving some suicidal. But the recent and sudden escalation of the problem hasn’t taken the government by surprise; quite the opposite.

“I was talking publicly on TV in 2019 about HRT shortages, so it’s not new,” says Danzebrink, the founder of Menopause Support. “It’s been a real eye of the storm in the last six months, but menopause and HRT should have been prioritised by the Department of Health back in 2019 when we had shortages then. The only reason a tsar has been appointed is that organisations like mine have encouraged women to write to the department and tell them exactly how these shortages are affecting them.”

The response those women received? “It has been insulting.”

Around 1 million women in the UK are using a form of hormone replacement therapy to help them deal with the often destabilising physical and emotional symptoms of perimenopause and menopause. Overnight, their lifeline has been interrupted and the consequences can be huge. Many women choose the treatment because their symptoms have prevented them from living a normal life.

It can take three to six months for a patient to find the right combination of hormone treatments to suit her, to regain her energy and ability to function well at work and in her personal life. Menopause experts and hormone doctors warn against suddenly coming off a drug that works for them – and yet this is now the scenario that hundreds of thousands of women now unexpectedly face because they can’t find a pharmacist able to fulfill their prescription. The anxiety this provokes is overwhelming.

Hannah, a 49-year-old personal trainer from south London, started taking HRT a year ago after struggling with a range of symptoms including anger, anxiety and total exhaustion. “At 4pm I’d just have to lie on the sofa,” she says. She was prescribed Oestrogel, a topical hormone treatment that has faced the most widespread shortages, and settled on it after spending a few months finding the right dose for her. “It was all going fine until last month. I went to get my prescription and it had run out everywhere. I went around all the local pharmacies and I found one that would give me one bottle but was rationing it. That would last me two weeks. I’m calling around every day, trying to get lucky. If it runs out I will feel the effects straight away.”

Hannah has now resorted to trying online pharmacies and others out of her area, but with no luck. One pharmacy said they did not know whether stocks would ever be replenished at their branch. Another told her a delivery was due but that 40 women were ahead of her on a waiting list. A third told her to “be patient”.

But her medication is so finely balanced she doesn’t want to switch it, and now she’s scared about what lies ahead. Patience isn’t on the cards. “It’s one of those women’s issues that are overlooked,” she says. “In the last month I had more energy, I could get everything done, I could finally do my job. The cure is there and we should be able to get hold of it. It should be widely available. We shouldn’t have to be whingeing about getting it in Facebook forums. Perimenopause and menopause doesn’t need to be this hard. You shouldn’t have to fight this hard.”

HRT was first prescribed in the UK in the 1960s and proved a popular treatment until the early 2000s, when emerging medical evidence appeared to link long-term use of oestrogen replacement to rising cases of breast and other female cancers. The numbers using the treatment plummeted between 2003 and 2007 as doctors feared the risks outweighed the benefits for many women. Later research proved the reverse was the case: HRT has huge beneficial, protective effects against osteoporosis, loss of muscle strength and recurrent bladder infections, as well as removing debilitating symptoms of menopause, giving women more energy in the post-fertile years. The link to breast cancer was found to be incorrect, but it has taken many years for the attitudes of GPs to catch up.

What to do if you can’t get hold of your HRT prescription – advice from Diane Danzebrook, founder of Menopause Support

- Don’t “do the dance” of going between endless pharmacists and your GP, as that takes time that most people don’t have. Instead, arm yourself with the information you need first

- Ask your pharmacist what prescriptions they are able to fulfil and when

- With that information, speak to your GP about possible alternatives to switch onto during the current shortage and agree a new regime

- Allow yourself three months to adjust to any new medication

- Speak to your employers about what’s happening. Let them know you may be adjusting to new treatments or withdrawing from HRT. Let them know you may be adjusting to new medications or withdrawing from HRT, and might require extra time or flexibility at work

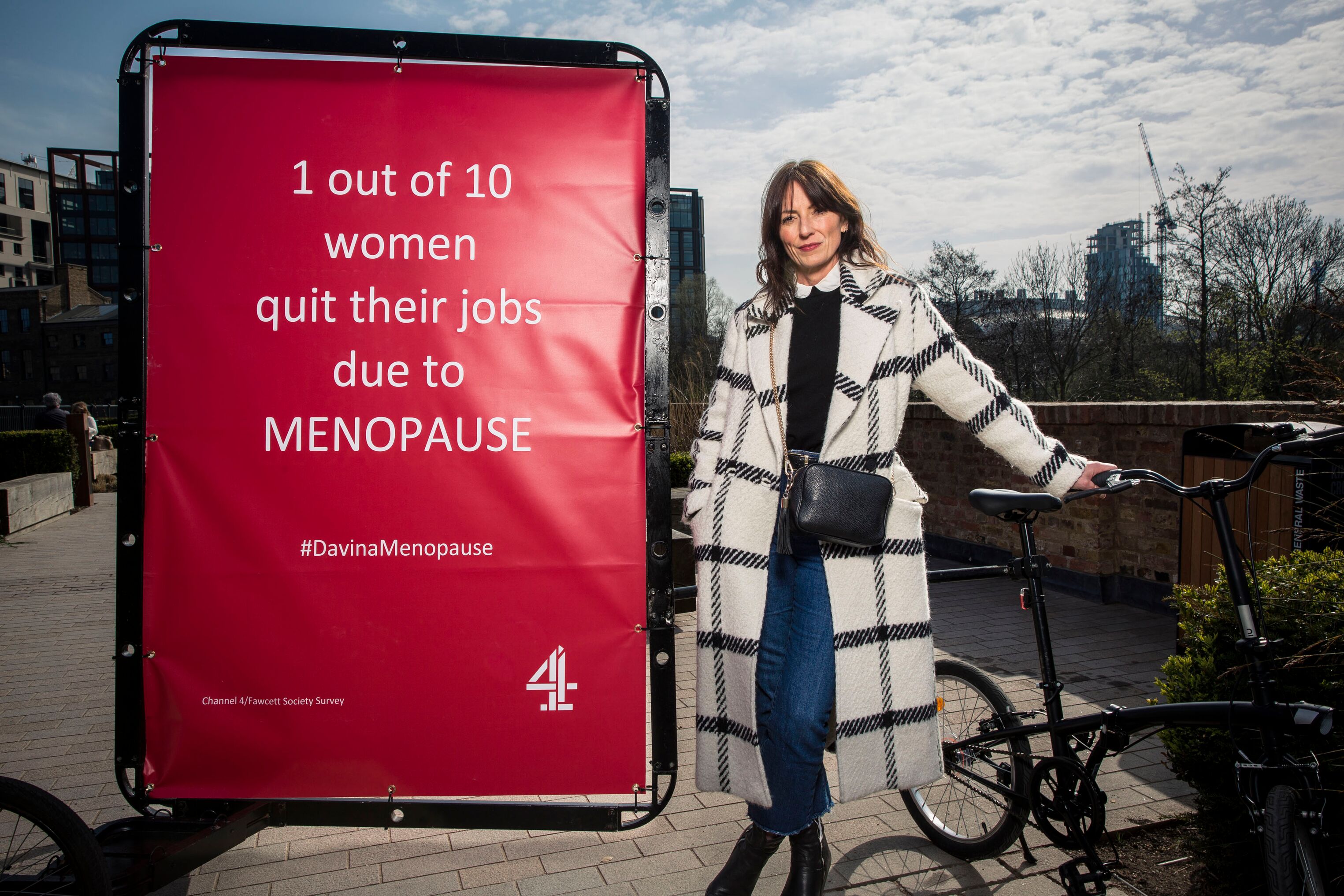

Yet, alongside the effects of Brexit on the medical supply chain into Britain, a key cause of the shortages has been growing demand for HRT. Women are educating themselves about the menopause; they are talking publicly about what is happening to them and how HRT can help improve their quality of life. Popular culture has locked on to the fact that menopausal women are a huge, under-sold demographic. In recent months alone there has been a groundbreaking documentary on the experience of menopause by TV presenter Davina McCall, a website about the process and natural HRT aids by the ex-Britpop groupie Meg Mathews, books by Mariella Frostrup and Andrea McClean and a hugely popular podcast, The Shift, presented by journalist Sam Baker.

Thanks to all their advice, women commencing the process of perimenopause know what symptoms to look out for – and know their rights around HRT. As a result, demand for prescriptions is rising fast, and the manufacturer of the most popular topical treatment, Oestrogel, is struggling to keep up.

Baker, whose book The Shift: How I (lost and) Found Myself After 40 – and You Can Too, which accompanies her eight-series podcast, says women are no longer willing to just suffer what previous generations accepted as a fact of life. “What you’re seeing now is Generation X becoming menopausal and saying I want to carry on living my life, I’m not going quietly into my dotage. People are going to GP and saying I am entitled to HRT – and if they won’t prescribe it, they want a second opinion.”

Women are also educating each other, building communities and support groups on social media sites including Facebook. Baker found herself infuriated by the coverage of the “black market” in HRT drug swapping between women. To her, these were groups that had better education on the products, their benefits, dosages and effects than many of the GPs that had prescribed them. But the fact that they had to resort to this is a sign of the way health policy has let women down in recent years – particularly, as always, older women.

“Brexit has affected supplies of pretty much everything,” says Baker, “this being a female-focused thing has really taken a back burner. If you’ve been taking HRT and you suddenly stop tomorrow? Well, I feel for those women.”

One woman I spoke to said she couldn’t get HRT from the GP but could afford to go private if she saved. It’s not comparable to designer shoes

It’s not just the shortages of supply through pharmacies that are causing problems for women who want to use HRT. The lack of training about the menopause – its symptoms and effects and the safety of HRT – among GPs is a stumbling block that many women face long before they even have a prescription to fill.

Baker interviewed more than 80 menopause patients when researching her book, and reports that the overwhelming majority had a bad experience discussing and treating menopause with their GP. Her subjects described a mixture of total ignorance and lack of empathy towards women, she says, with doctors telling patients reporting debilitating symptoms to just, “get on with it”.

“Can you imagine anybody saying that to a man? That this is just life now?” Baker says. “For a long time we have been treated as if our quality of life is a luxury. One woman I spoke to said she couldn’t get HRT from the GP but could afford to go private if she saved. It’s not comparable to designer shoes. It’s not a lifestyle choice: the luxury of not feeling s***.”

So many report similar difficulties in getting their GP to take them seriously. Jo Roberts, 40, a civil servant from Surrey, began to realise she was in perimenopause during the first lockdown. After running like clockwork for decades, her periods stopped completely. Then the anger started. “I would have the rage, telling my husband that he needs to get away from me for no reason. It was absolutely horrendous and I felt like I was the hulk. This was totally new for me, to feel angry about someone just being in the same house as me.”

The moment she describes as the “final straw” came during her 40th birthday celebrations. “I spent it with my friends and family. I had the heaviest period and I ended up telling all of them – including my 4-year-old goddaughter – to go away and leave me alone. These are people I love. I immediately knew this was not the situation I wanted to be in.”

But when she reached the GP, her symptoms were dismissed as anxiety despite the fact that her mother went into menopause at 36, and by now she was also experiencing vaginal dryness and night sweats. She pushed for HRT and was eventually given oestrogen replacement, but she has researched her own hormone profile and is pushing for testosterone too – with no luck. “My GP practice is all female and it’s still been quite short shrift. I’ve done all the research, I’ve sent them the [academic] articles. I’ve explained how I’m feeling and it seems like even now I’m not taken that seriously.”

Instead of being prescribed a bespoke hormone replacement, like other women, she now finds herself at risk of losing even the limited supply she had. Without it, Roberts says, “I’d have to leave my work and I would probably have to not work at all because I physically wouldn’t be able to cope. I wouldn’t be able to cope being a parent either.”

Getting a GP to take menopause seriously is even harder if you face symptoms early in life, as 38-year-old publisher Cat Crossley, from Bradford, found out. She first went to the doctor a year ago after experiencing suddenly lengthened menstrual cycles and heavy, flooding periods, causing her anxiety. She booked an appointment with a male GP.

“I went in thinking I will get adequate medical care from a man, but he gaslit me about my experience of my body,” she says. “He wasn’t directly rude, but he dismissed me. He ran through all the reasons it was unlikely and suggested some examinations.” Crossley explained that she’d already undergone these tests over previous years of gynaecological issues. “At the end of a lot of questions, he said the next thing to check for is early menopause – as I’d said.”

On her second visit to a GP she asked for a referral to a menopause clinic. After a long negotiation she was referred to a centre far from her home, and she doesn’t drive. “The journey would potentially be a few hours to get to a clinic that’s providing this specialist help,” she says. “It’s specialist, but how can it be that rare? I would like to talk to someone who knows something more than I can glean from reading a couple of books. It doesn’t seem like that’s too much to ask.”

Crossley is still waiting for that appointment and still waiting for an HRT prescription. Her experience explains why so many choose to shun the NHS for private menopause care. In the private sector, HRT is prescribed on a personalised basis, replacing the exact balance of hormones a woman has lost during her perimenopause period, rather than off-the-shelf prescriptions.

There are some unkind or short-fused comments about how the shortages are not life and death, but it can really affect the functioning of an otherwise well person

Dr Martin Kinsella, a menopause and hormone expert, says he’s seen a rise in enquiries about his service in recent years, but that the short supply of HRT on NHS prescription and the dismissive attitudes of family practice doctors has led to the growth in interest about his work. He is pleased that women are starting to realise what they can demand of their physicians.

“Half a million HRT prescriptions are being written every month,” he says. “It sounds a lot, but when 12 or 13 million women in the UK are suffering, that’s a lot of women who are not being treated.”

Kinsella’s clinic offers customised hormone treatment which is considered an “off licence” use of drug treatment, but which matches the hormones lost to each women – not just oestogen, but also progesterone and testosterone. This is complex medical work where, so far, the NHS is lagging behind.

“Every single woman has a different level of hormones and requires different doses,” says Kinsella. “Surely the best way is to take a full blood test, examine all the hormone levels and then conservatively balance and restore the optimal levels for that person? That’s why with customised bioidentical HRT we can keep those patients on hormones for life. They can be on them until their eighties and nineties. What good is it putting women on standard HRT to only tell them five years later that they need to come off it?”

One of the biggest reasons for a referral to Kinsella is a woman who has been on HRT is being forced to come off it by their GP and is now seeking a second opinion.

Some doctors warn against clinics like Kinsella’s, claiming the approach to hormone matching is “unregulated”. He describes such comments as “a play on words” and a “dangerous statement to make”.

“All hormones are very much regulated,” he says. “The CQC regulates all the clinics, the pharmacies are regulated, but, because it’s suitable for one person, it can’t be licensed on the shelf. It will always be prescribed in an off-licence way.”

He believes the NHS is long overdue a proper investment in time and resources to explore women’s medicine in the middle and later years of life.

Of course, there are those within the health service who are already seeking to make change. Surrey GP Dr Radhika Vohra, also a trustee of The Menopause Charity, is fighting for better training for family doctors on menopause symptoms and treatments, and to see hormone balance for menopausal women taken as seriously as diabetes and thyroid treatment inside the NHS.

“We need to start to take it seriously,” she says. “There are some unkind or short-fused comments about how the shortages are not life and death, but it can really affect the functioning of an otherwise well person.” She also wants to see an end to the postcode lottery of provision in the UK, where in some areas there is more access to a wider range of HRT products – not a situation that is repeated for diabetes or thyroid management.

Vohra, who believes she only had one hour of teaching on the menopause in medical school, trains new doctors and is heartened by the awareness and positive attitudes of trainees, describing them as “keener to change practice”. But if supply can’t meet the new demand among women, and awareness among prescribing doctors then the pharmacies won’t be able to keep up. Shortages of Oestrogel, for example, led to supportive doctors switching their patients to other new products such as hormone sprays, only to find that the increased demand on that supply chain was destabilising other women who were settled on that alternative treatment already.

That’s not good enough, Vohra says. “For women who have been empowered, it disempowers them slowly. For some women, it has made them suicidal. Women should not, and will not, let it go because they’ve had a taste of how much better they can feel.”

What difference will Javid’s HRT tsar make? Campaigners including Danzebrink believe the Department of Health has been forced, not moved, into making the appointment because, given the headlines, “it would have seemed incredibly poor if they hadn’t done anything”. The cost of getting it wrong could be millions of female votes at the ballot box.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments