The Philosopher of Auschwitz, By Irène Heidelberger-Leonard, trans. Anthea Bell

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

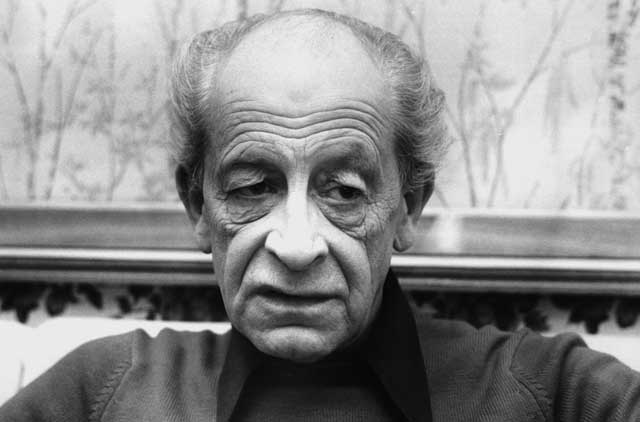

Your support makes all the difference.Jean Améry had always wanted to be someone extraordinary. Yet when he became just that, lauded by post-war writers, from Heinrich Böll to Alain Robbe-Grillet, Ernst Bloch to Günter Grass, Alfred Andersch to Ingeborg Bachmann, he still felt he had not achieved enough. He was the darling of the German media. Prizes and honours were raining down: from Switzerland, which had provided him with a living, working relentlessly hard, as a journalist and critic after his survival of the concentration camps; from Germany, the land not only of thinkers and high culture, but also of perpetrators, where he had not set foot during the intervening years; and even from Austria, from which he had been hunted "like a hare" in 1938, but where he returned to take his own life in 1978.

This self-doubt, this desire to be someone other, or someone different in addition –a celebrated man of belles-lettres as well as the fêted essayist – was the flip-side to a writer who took his place beside Primo Levi and Theodor Adorno, while at eloquent odds with both, as chronicler and unique analyst of the experiences of the Holocaust. His searing honesty and clarity brought a further essential level to the discussions taking place in the Germany of the 1960s, prompted by the Eichmann trial and Hannah Arendt's The Banality of Evil, the debate of the Statutes of Limitations, and the Auschwitz trial which started in December 1963 in Frankfurt.

Améry's 1964 essay collection, published in English as At the Mind's Limits, tackles in a subjective, yet highly analytical way, the "situation of the intellectual in the concentration camp". It examines how the mind, or intellect, deals (it cannot) with the overwhelming realities of torture and the camps of the Holocaust. These landmark essays made an enormous impact. Not enormous enough, however, for Améry to feel he had wholly "arrived".

Irène Heidelberger-Leonard's meticulously researched biography, in Anthea Bell's elegant translation, is empathetic, but true to the ambivalences of her fascinating and troubled subject. A rich and intellectually satisfying portrait both of the man and his times emerges, from his loyalty to the tenets of the Enlightenment, his forays into 1930s Viennese neo-positivism, and his belief in the power of education (one of his greatest regrets was not to have been taken up fully by students, nor by the New Left).

When his Jewish-ness could no longer be lived on the periphery with the Nuremberg Laws, his intellectual journey continued in Belgium. There he joined the resistance. After the camps, it was in exile in Brussels that he became "Jean Améry", an anagram of his birth name, Hans Mayer. Sartre, Thomas Mann, and Proust remained constant companions in a life inextricably shaped by thought. As does the presence of the option of death, even before the Auschwitz experience, as his second wife Maria writes in an imaginary letter to him: "Auschwitz number 172363 – for that number sealed your fate... But there was so much else; it was all in you from an early date. It was no coincidence that as a very young man you loved only the poetry of those poets who wrote of decline, melancholy and death."

Améry's legacy is a body of work that still makes essential reading today, be it his essay on "Torture", or his characteristically provocative On Ageing and On Suicide. This prize-winning biography provides the perfect platform to re-enter arguably one of the finest minds of the last century.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments