Marilyn, The Passion and the Paradox, By Lois Banner

This investigation tells us more than ever about Monroe's childhood - but do we need to know?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the 50 years since Marilyn Monroe's death, an industry has grown up around her. She is one of the most instantly recognisable celebrities of the 20th century, endlessly reproduced on posters, t-shirts and even handbags. Monroe means something to a great number of people, but what that might be isn't so easy to define.

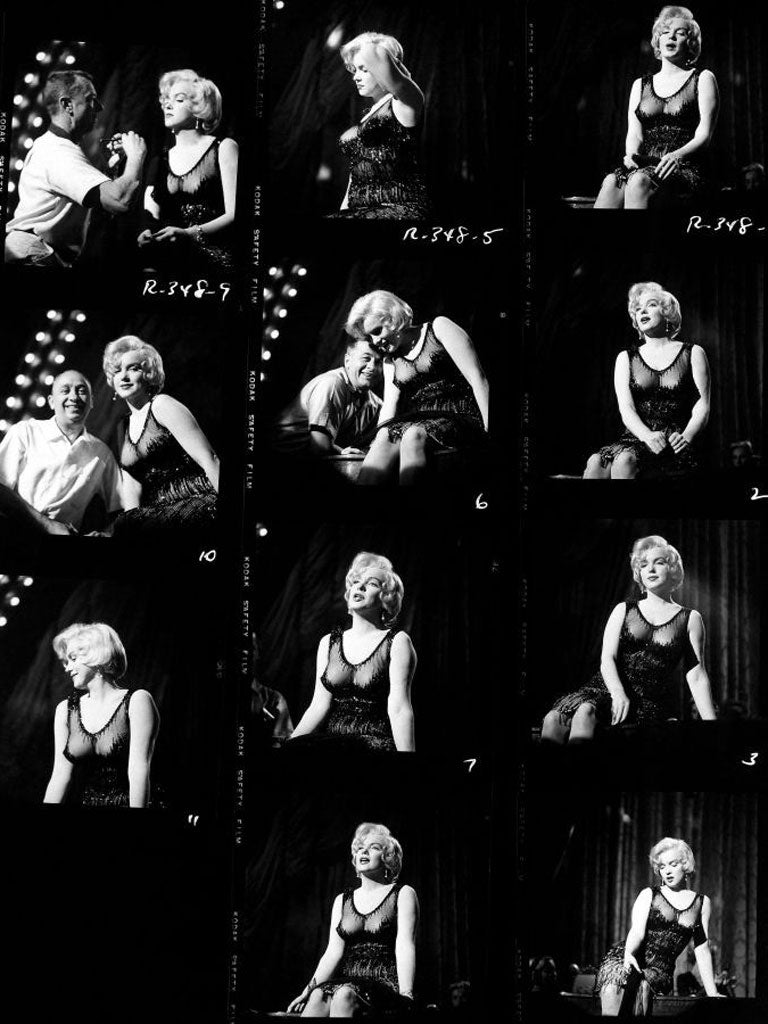

The anniversary of the night in August 1962 when she was found dead in bed offers an irresistible opportunity for fresh readings, informed by the pre-occupations of our time. One is the meaning of celebrity. In her weighty volume, historian Lois Banner remarks that Monroe was happier with still photographs of herself than her films. It speaks to an aspect of her character which feels incredibly modern. When narcissism no longer carries a stigma, she is the precursor of a stream of celebrities whose most obvious talent is self-promotion. Working with just a photographer she was in control, unlike a film studio where she clashed with directors.

Banner is conscious of Monroe's skill in projecting herself, a "rare genius". It isn't so rare these days, but Banner's purpose lies elsewhere, offering a new interpretation of the star's life which draws on feminism and the history of gender . It's certainly the case that Monroe's story has been handled in the past by biographers and critics who don't share that perspective, including the novelist Norman Mailer and her ex-husband Arthur Miller. Mailer's book on Monroe is a drooling rehearsal of a particular species of male fantasy, while Miller's play After The Fall presents her as a monster.

Mailer's book is a warning to any woman who aspires to be "the new Monroe". The problem with Mailer's interpretation is not that it's wrong but that it cuts off feminist re-readings at the knees. Monroe was almost certainly sexually abused as a child, and her vulnerability and eagerness to please were central to her success. For Mailer, she was the embodiment of easy sex, the woman who promised that it "might be... dangerous with others, but ice-cream with her".

Banner's book provides the most detailed account yet of Monroe's fractured childhood, identifying 11 families who provided homes for her. Born in 1926 – she would be the same age as the Queen if she were alive today – Marilyn grew up as Norma Jeane Mortensen. Her mother Gladys gave her the name of her second husband, a meter reader called Edward Mortensen, but Monroe always believed her father was Stanley Gifford, a supervisor at the Hollywood film studio where Gladys worked.

Neither man played a role in her upbringing, and Norma Jeane moved from one step-family to another as her mother suffered a series of breakdowns. Gladys spent time in mental institutions, leaving Norma Jeane with a lifelong fear that she had inherited her instability.

She spent seven years in California with Ida and Wayne Bolender, evangelical Christians who took in foster children. Banner thinks that the significance of religion has been overlooked in Monroe's formative years. The Bolenders believed in sin and redemption, organised nightly Bible readings and took Norma Jeane, aged six, to a dawn service at the Hollywood Bowl.

A later foster mother, Ana Lower, introduced her to Christian Science, a mystical religion founded in 1879 by Mary Baker Eddy. Monroe would later convert to Judaism when she married Miller, but the religious fervour she encountered as a child infused her nightmares with witches and demons. Nor did it help with the guilt she was made to feel when Ida caught her in childish sex experimentation, possibly masturbation, and whipped her for touching the "bad part" of her body.

The sexual abuse happened when she was eight years old, after she left the Bolenders, and was carried out by an elderly man who has never been firmly identified. Banner sees this episode as a key moment in Norma Jeane's life, producing "dissociation" and her "major alter ego" Marilyn Monroe: an alternative self, "sexual and self-confident". Obviously, "Marilyn Monroe" was an invention, but Banner's own account of Monroe's relationships with men reads like a catalogue of exploitation and abuse. Early in her film career, after she was signed by Twentieth Century-Fox in 1946, she became a "party girl" – one of the aspiring actresses expected to entertain visiting executives. Banner says that one of the things Monroe learned in this period was to be adept at sex, including fellatio. She would later call Hollywood "an overcrowded brothel".

Her film career was chequered, turning into a constant struggle with studio bosses who wanted to keep her in the "dumb blonde" role. Her marriages suggest a powerful need for male affirmation; her first husband was a high-school athlete, her second the sporting hero Joe DiMaggio, and her third (Miller) the country's pre-eminent intellectual. It's hard to imagine anyone as damaged as Monroe forming stable relationships but there's also a hint of something which has become common in the 21st century, namely short-lived alliances between very famous people who look good together in public.

Banner isn't the first feminist to write about Monroe; she was beaten to it by Gloria Steinem, whose 1986 biography is a lovingly-crafted rescue fantasy. But Banner's purpose seems two-fold: to claim Monroe as a kind of pre-feminist icon, and to establish herself as the foremost scholar in a crowded field. Her Marilyn is difficult, ironic, insecure, bisexual; she's also clever - far from an original claim.

Banner's biography dispels some myths about Monroe's childhood but the sheer quantity of detail is daunting, and her prose is sometimes excruciating. I'm not convinced that Monroe's life has a positive message for women. As I once observed in another context, her enduring appeal suggests that (some) gentlemen prefer dead blondes.

Joan Smith is Political Blonde www.politicalblonde.com

Buy Marilyn (Bloomsbury) from www.independentbooksdirect.co.uk for £16 (RRP £20) including postage or call 0843 0600030

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments